Game review: Codename ICEMAN (1990)

Studio: Sierra On-Line

Designer(s): Jim Walls

Part of series: —

Release: March 1990

St. George’s Games: Complete playthrough (5 hours 10 mins.)

Basic Overview

Just as it is in any other artistic medium, «the worst game ever made» is never really the worst game ever made. The worst anythings ever made are, first and foremost, those that lack imagination — mechanical, soulless copies of original and (at one time) exciting ideas, driven either purely by profit or, more often, by the simple necessity of «sink-or-swim»: you gotta write, paint, film, or program at all times, or prepare to get eaten while you just sit there twiddling your thumbs for lack of «artistic inspiration». We read, watch, listen to, and/or play a lot of those, usually without any extreme emotional reactions — just perfunctory ones — then, once finished, we put aside the project without ever returning to it, and maybe even forgetting about it altogether on the very next day. These are the worst ones, though we never really call them that. Instead, when pressured to come up with «the worst album we ever listened to», we strive to remember stuff like Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music — and if you are a child of the Eighties, chances are that Codename: ICEMAN will be one of the first titles to pop into your head at the respective call for «the worst game ever made».

The thing is, of course, Codename: ICEMAN is the farthest thing from such a game, because one thing it never lacked was imagination. On the contrary, the game, masterminded by the same retired police officer Jim Walls who had just proven his critical and commercial viability with two installations of Sierra’s Police Quest, represented a bold and challenging attempt to push the agenda of virtual realism in computer games even further — as far as it could substantially and technically go in 1989–1990, and, (unfortunately), even quite a bit further than that. At the time of release, it looked, sounded, felt, and played like no other game ever made, in full accordance with Sierra’s self-challenge to constantly stay on the cutting edge in an era of ever-increasing demands and possibilities of the computing world. The fact that it became such a flaming disaster is one of the more fascinating phenomena from that era, and a viable reason for historically-minded players to pick it up even today and try to experience, on their own, what exactly went wrong with it — at least, for as long as you can stand the torture.

I am not entirely sure if the original pitch was Jim’s own or if he was seduced into the genre of spy thriller by Ken Williams or any other Sierra executive, but one thing is clear: he did work on the game with the same level of dutifulness and diligence as had previously been invested in the Police Quest series. By 1989, James Bond-style games were nothing new, but most of them were pure action titles; no one had yet released a proper adventure game based on the style, and certainly no one had tried to do what Jim was trying to do — combine an adventure game story, with puzzles to be figured out through the usual text parser, with meticulously crafted simulations of real-world situations, which would realistically put you in the shoes of a true jack-of-all-trades James Bond, knowledgeable about everything from CPR procedures to operating a submarine to finding the right diameter for a steel washer reinforcing a rocket shaft to knowing his way around the ladies, of course.

All of that and much more found its way into the game, so when an excited reviewer from the June 1990 issue of Games International called it “the most sophisticated adventure game I have ever played“, it was no exaggeration: at the time, it was the most sophisticated adventure game ever designed. So sophisticated, in fact, that it left behind a trail of virulent hatred which keeps flashing with bright acid colors even today, every time an intrigued new player digs out this fossil and decides to take on the challenge of inserting his head into its age-old pillory hole. Whatever positive emotions some of the original reviewers, seduced by the game’s novelty, could have experienced back at the time were very quickly washed away by the understanding that, both as a «story» and as a «game», Codename: ICEMAN was a spectacular failure. Apparently, while police procedurals and spy thrillers might have some obvious elements in common, having a former police officer work on both genres was not such a hot idea — something that Ken Williams understood (or didn’t) a tad too late.

In retrospect, few things about the history of Sierra are marked with as much common consensus as the idea that Codename: ICEMAN represented the ultimate nadir for the company, even at a time when, on the whole, it was arguably at an early creative peak, tossing off creative ideas like pancakes and modestly revolutionizing the gaming world with each new released title, or at least close to that. I have no desire to challenge that consensus — I literally hated the game almost every second of playing it, even in a recent replay while recording it for my YouTube series. Yet my allegedly masochistic streak also made me admire just how many different ways the game found to brutally punish and mutilate me for no particular reason; it was like the ideal video game equivalent of the perfectly designed, ingeniously sophisticated Chinese torture, intended to wring out every single ounce of pain from each single nerve in your body for the longest possible amount of time. At the end of it, I am almost proud to look back at the recorded legacy — all challenges overcome, maximum possible score achieved (with help from various guides, of course), and no satisfaction or meaningful purpose derived whatsoever. To quote Dan Aykroyd from SNL’s Samurai Night Fever, “this is the life — to be young, stupid, and have no future at all!.. I love Brooklyn Codename: ICEMAN!“ Let’s take a look at the various anti-fun aspects of this game to see why it deserves so much for you to waste as many hours of your worthless life as possible on its stupidity, brutality, and monotonousness.

Content evaluation

Plotline

“Welcome to the beautiful island of Tahiti, where warm South Pacific breezes caress the emerald clear waters of a sun-filled paradise“. Hilariously, Codename: ICEMAN opens up to you not unlike a Leisure Suit Larry game, which is probably not a coincidence given that the most recent title in Al Lowe’s titillating series also took place on a tropical island — with the titular hero walking around its beaches and jungles in the exact same Hawaiian shirt and ogling bikini-clad babes with the exact same intent as “Commander John B. Westland of the United States Navy, enjoying a well-deserved leave from his recent assignment“. In fact, the first half hour or so of the game do play out much like a Larry title, with one crucial and fatal difference: absolutely nothing about it is as amusing or sarcastic as the typical content in an Al Lowe game from the «golden age». Whenever Larry Laffer tries to pick up a random lady, what we usually get is a satyrical poke at embarrassing masculine behavior or at an equally embarrassing feminine stereotype. Whenever Commander John B. Westland tries to do the same, I guess we get a realistic equivalent of the average officer of the United States Navy, strictly following government-approved protocol of picking up random ladies for United States Navy officers.

There was not a chance in hell that the storyline of the game could succeed in any way, because from the outset and until the very end Jim Walls had to observe two directives in stark contradiction with each other. On one hand, he had to design an «exciting» thriller adventure, a James Bond-style fantasy that would have it all — an omnipotent superhero of a protagonist, exotic locations, heavy action, stealth and subterfuge, political games, hot girls, and the imminent triumph of coolness over evil. On the other hand, he also had to apply the realistic experience acquired in his design of the Police Quest series to the game. The hero would be a James Bond, but not the usual «magical» James Bond — the game would have to show you all the complex, sometimes technical, sometimes bureaucratic intricacies of working as a real-life C.I.A. agent under all sorts of circumstances, from relaxing to routine to extreme. Imagine a movie in which Mr. Bond, before putting on his jetpack, has to spend twenty minutes scrutinizing it for defects, then has no choice but to make a detour to the local general goods store for some duct tape and a couple extra plastic caps. That’s Codename: ICEMAN for you.

Not that its story would be any good even if it were completely stripped of all the in-game «realism». Strive as he could, Jim Walls was just a retired police officer who may have read some spy thrillers and watched some action movies in his life, but he was no Ian Fleming or John le Carré when it came to designing an original plot. A Middle Eastern terrorist organization, (naturally) backed by Soviet financial and logistic support, kidnaps a U.S. ambassador and holds him hostage in a remote Tunisian location. Your task is to reach the identified hidden location of the terrorists by sea — in a submarine, no less — and extract the hostage before an international incident brings the USA and the USSR into open war. (Don’t ask me exactly how, I’m not sure I remember or if I want to remember). Along the way, you will have to blow up an entire Russian destroyer, sink a rival Russian submarine, demolish a Tunisian oil rig for distraction, and do a few other cool things that all those cool American war heroes supposedly do on a regular basis. All in a day’s work and in the line of duty, somehow without triggering World War III despite giving the Russians every good reason to do just that. (It’s probably a good thing the country was already run by Mikhail «Mr. Softie» Gorbachev at the time — what would Comrade Andropov say about American submarines sending a Russian battleship to the bottom of the sea?). It’s the exact same kind of plot that ChatGPT could create today in three seconds flat (and make it far more politically correct than could have entered Jim’s mind in 1989, for better or worse).

To be more accurate, any kind of «plot» really only starts around the final quarter of the game. The first quarter, taking place in Tahiti, is mainly about the Commander hitting it up with the local ladies (one of whom also turns out to be a secret agent, although you have to be a real expert in pixel-hunting to find the clue that leads you to realize this). The second half, taking place inside the submarine, is mainly about the Commander steering the submarine (and wiping out an occasional Russian ambush). And only near the end does the actual action — with stealth and subterfuge, masked identities, shoot-outs and car chases — finally take place, making the game a wee bit more fun if you have made it all the way to this point, which is not very probable (I think the absolute majority of players must have rage-quit in the early stages of the submarine control simulation). Even then and there, I suppose that the pinnacle of Jim Walls’ originality (earth-rattling SPOILER ahead!) is having your hero conceal a gun in a plate of food on special delivery to the starving ambassador — which the guards never discover because, apparently, it’s in real bad taste to show mistrust in your local delivery man in Tunisia, or you’ll be getting eight-year old lamb for your gyros for the rest of your toothless life.

Perhaps it is for the best that Jim does not even try to introduce any sort of «moral message» into the story. Actually, the overall message is best summarized in the congratulatory speech delivered unto you by your superiors at the end of the game: “Had the incident been successful, the effect would have left the USSR manipulating the bulk of the world’s highest-grade crude oil. This, my friend, would have had definite negative impact on the economy of the United States!“ The lines are delivered without the slightest hint of irony or cynicism — but at least they are fully consistent with the overall ideological flow of the game. It’s not an exaggerated, gung-ho show of patriotism (you do have to salute the flag every once in a while, but that’s mainly because it is required by procedure), however, Commander Westland is just the kind of guy who would seem to be happy to know that he has just prevented some definitive negative impact on the economy of the United States, in addition to saving a human life and all. So this is not a true James Bond-type story after all — while Bond is a complex character whose true motivations we never really know (but religious loyalty to Her Majesty’s Secret Service is certainly the least of them), Johnny Westland is as simple a guy as they come. He really lives for that Naval Distinguished Service Medal, that one.

On the whole, the plot is so stripped down to the bare essentials of all the typical spy and action movie tropes that the game must have felt substantially outdated even by the adventure standards of 1989–1990. Had it been designed around the same time as, say, Roberta Williams’ earliest King Quests, we could excuse this by the pioneering nature of the effort. But with game budgets already being a little bigger, and the technical system capacities already allowing for a bit of creative writing along with your puzzle-solving, Codename: ICEMAN is like the straight, sober, humorless, law-abiding next door neighbor of yours whom you can always rely on to call the cops at the least sign of trouble, but in whose presence you’ll always think twice about cracking a joke because that particular penthouse will likely stay out of elevator reach forever. Even Jim’s own Sonny Bonds had more of a personality than Commander Westland — and even his thoroughly «patriarchal» romance with Sweet Cheeks Marie had more flame and passion to it than the hastily scribbled-in «affair» between the Commander and his part-time lover, part-time work partner Stacy, the proverbial «mystery woman» who’s somehow got less enticing mystery to her than the working girl Larry meets for two minutes in Lefty’s bar in the Land Of The Lounge Lizards.

Puzzles

But fine, so maybe Codename: ICEMAN was not designed for its plot, maybe the entire story was just there as a strictly formal, nominal setting for presenting the player with a set of intriguing and exciting challenges, designed to test our intelligence, dexterity, and discipline. Maybe — even if it really goes against the entire classic philosophy of Sierra On-Line — Codename: ICEMAN is just a hybrid puzzler / action game, and we should no more penalize it for the lack of passion or originality in the «plot» as we should, say, penalize a Mortal Kombat game. What, then, are its chances?

Well, let’ say that, more often than not, the quality of a puzzle-based video game is determined by the quality of its first serious puzzle. In this particular case, Commander Westland’s first challenge (apparently, an optional one, but one you are very likely to get embroiled in, and you do need it for points) arrives straight off the bat as he joins a bunch of bikini-clad girls on the Tahiti beach in a game of volleyball. One of the girls accidentally hurls the ball into the sea, goes out to get it, gets caught up by the current and requires you to pull her out of the waves — and then resuscitate her by giving her CPR. A somewhat realistic scenario — which might be construed as a good thing, until you realize that in order to «solve» the puzzle, you actually have to type in all the proper steps for CPR right out of your manual. “Call for help“, “establish the airway“, “look, listen, and feel“, “give two good breaths“, etc. Technically, it’s a rather sadistic form of copyright protection; substantially, it feels like a forced basic first aid course which you probably did not sign up for when handing over your money. One thing you can expect, though, is for this particular level of «fun» to hold steady throughout the rest of the game.

I must say that deep down in my soul, I can’t help feeling a weird sort of admiration for Jim Walls — the man who gritted his teeth, gripped us in his iron grip and force-fed us gruelling military discipline where we were probably hoping for a fun-filled 007-style experience. Forgot to salute your superiors? Points off, or game over. Forgot to check the proper functioning of your onboard arsenal? Prepare to get fucked several hours later when you least expect it. Too lazy to spend time on the (admittedly elementary) math of decoding encrypted messages? Might as well turn in your badge. You really want to experience the life of a secret agent? Learn to write your reports according to form, you lazy nitwit. You thought all James Bond does is shoot his pretty guns and make love to gorgeous models? Uh-uh. The real James Bond spends his time learning the difference between the different sizes of nuts and washers.

I don’t think the game actually has even a single real «adventure game puzzle» — well, maybe other than that bit at the very end where you have to figure out an (absolutely batshit-crazy) way to infiltrate the compound with the Ambassador and get the guy out of there. Everything else literally depends on how attentively you read the enclosed manual and how closely you follow the given instructions. On those tiniest occasions when the game deviates from standard procedure, you end up wishing it wouldn’t — for instance, it is not enough to not to forget to retrieve your ID after your visit to the Pentagon, but you must also check that you have been given the right one, otherwise it’s game over after a short while. Then again, I don’t know, maybe that is supposed to be the standard procedure — after all, don’t we all know that all federal employees are latent doofuses and couldn’t even wipe their asses properly without Elon Musk standing behind them with a wad of toilet paper?

However, as tedious as we shall find the rigidity of the «puzzles», it’s really nothing compared to the physical torment of handling those submarine controls. It takes ages to understand which buttons to push with which heyboard shortcuts, and even then you’re still at the mercy of the degree of responsiveness of those controls (many a time have I had a game over by being too quick or too slow with that blasted rudder). The battle sequences frequently randomize the outcome: whenever an enemy launches a torpedo, your best bet is to grit your teeth and just pray it doesn’t hit you, and that’s after you have lowered your submarine to just the right depth (if you haven’t, no prayer in the world will be sufficient to save you). In yet another awful sequence, you have to follow another guide sub to your destination, and it takes ages to properly understand what you are really required to do so as not to lose proper track of it. I can safely say that, for all my willingness to endure the often unfair challenges hoisted upon me by Sierra games, the submarine segments of Codename: ICEMAN have come the closest to become the breaking point (thank God for helpful Internet walkthroughs — but who could have predicted those back in 1990?). As subjective as the border between challenge and torture can be, I think that few people even back at the time could refrain themselves from rage-quitting, and that only the strangest minds in the world could endure something like this today. (But I did, in preparation for this review!).

Now, truth be told, as in many games, if you understand exactly and precisely what you have to do at any given moment in the game, the challenges are generally tolerable. It isn’t that difficult to control the submarine; it isn’t that tough to keep the proper distance from the other sub; and even that final chase sequence, where you have to escape the terrorists in a rickety old van over the mountain paths, isn’t too challenging once you have understood the proper pattern of action (speed up, slow down before a turn, speed up, slow down again, and so on). But the game itself only delivers the basic instructions; all the strategies of action you have to figure out for yourself, and doing this under stressed-out conditions that require swift and precise coordination is barely possible. And if you happened to get the game under the innocent impression that it was going to be just another Sierra adventure game — heck, even if you thought it was going to be similar to a Police Quest game, where the worst thing your clumsy fingers could do was to run a red light or crash your car into the sidewalk — well, then you and your money would truly be fucked.

Again, in theory, I can understand and respect Walls’ vision for the game. There is nothing wrong in wanting your audience to relive the realistic experience of a secret agent / submarine pilot / missile shaft repairman / medical brother through the medium of a video game. But it is impossible even today — and certainly it was even more impossible in 1990 — to emulate such an experience directly; an intelligent designer’s duty is to transform it into an experience that can be as captivating as it is intended to be educational. Jim Walls had no idea how to do that — perhaps even no desire to learn how to do that — and the result is just one big failed opportunity.

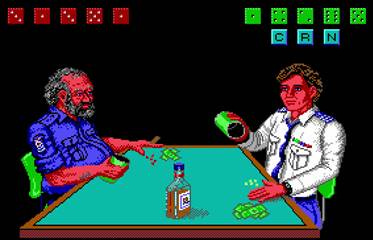

Besides, realism is overrated. One of the sequences in the game has you playing a game of dice against an opponent which, like most games of dice, is almost purely random — and, in a crowning twist of strategy, you are not allowed to «scum-save» because if you try to restore a game after losing, the machine catches you and (after several attempts) rightfully accuses you of cheating, which forfeits the match in your opponent’s favor. Granted, that was a very novel and unpredictable twist — in all of Sierra’s previous games with a gambling algorithm, you could easily roll back after each loss — but in a game where almost nothing depends on the player’s skill, is it really permissible to just let random luck decide your fate? If that’s «realism», well, I suppose the next step should have been including a 15% random chance of dying from a heart attack at any given moment in the game (and push that up to 30% every time you have to battle or flee from the bad guys).

As always in Sierra games, a special challenge is to complete the game to perfection, collecting all 300 points. Discounting a handful of elementary bugs that might you prevent from ever doing that, there are some really odd combinations along the way — for instance, you have to win that dice game in order to acquire a useful gadget from the old sailor, but then later on in the game you must remember not to use that gadget (!), instead choosing a more difficult strategy of getting ashore in Tunisia that will land you more points. You must also know, somehow, that performing certain submarine tasks with more accuracy will net you more points than being careless — but the game itself never tells you about it until it’s much too late. Only a detailed, user-friendly walkthrough can guarantee complete success.

All in all, while I am ready to defend a lot of Sierra games to the death over accusations of poor, user-unfriendly design (in my mind, as long as you get accustomed to the classic rule of «save early, save often», the majority of your problems disappear into thin air), Codename: ICEMAN is where I draw the line and wholeheartedly recommend it as a classic textbook example of how not to design an «action-adventure» game.

Atmosphere

In theory, a game like Codename: ICEMAN should be thriving on atmosphere. It’s a spy thriller! The lush beaches of Tahiti! The bleak corridors of the Pentagon! The oppressive cramped interiors of a military submarine! The mysteries of deep sea diving! The yellow sands of the Sahara! The fanatical Arab terrorists! The hot girls posing as secret agents (or is that the other way around?)! The subterfuge, the chases, the shootouts! Sure as hell beats cruising around the shithole town of Lytton in your old police car all day, picking up deadbeats and writing reports.

It is quite a feat, then, that the entire game somehow ends up packing less atmosphere and immersive power than the first half hour of Police Quest. While Jim and the other designers did dutifully follow the formulaic requirements of a spy thriller (exotic locations / hot girls + stealth / military duty / heavy action), all the elements are presented mechanically, without any actual love shown on the screen. The shithole town of Lytton, for all it was worth, had a rudimentary open-world charm to it. It was alive and moderately active — you could go anywhere on the mid-size map, exploring and investigating. “Hey look, it’s a hotel, I can even take the elevator to the second floor!” “Oh wow, it’s a courthouse, I can go inside and talk to the clerk!” “Okay, while I’m feeling stuck, why don’t I go have a cup of coffee in that nice diner, chat up the owner lady and take a leak or something?” Somehow, the game managed to pull through a whiff of that cozy-cute provincial suburban atmosphere, so that you, Sonny Bonds, actually felt a little motivation for keeping law and order, so as not to let any random scumbags mess up the nice clean streets of the town of Lytton.

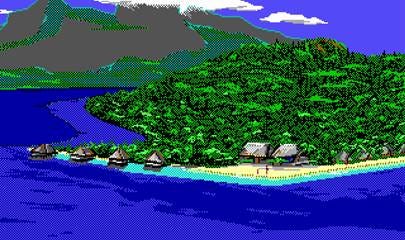

ICEMAN, in comparison, has little time to bother about the everyman. Commander Westland progresses through the game in linear fashion, not wasting too much time in any single location, and the closest place you’ll have to a cozy home will be the submarine with its incessantly annoying humming noise. There are some feeble efforts to stress the «exotic beauty» of Tahiti — the gorgeous contrasts between the beach sand and the dense forest, the bikini babes hopping around — but the scenery is just a couple screens, the only places you can freely go are the bar and your cabin, and the only answer you can get from the bikini babes is “she’s trying to ignore you“. Then there’s the Pentagon, apparently limited to a reception desk, one single corridor, and a conference room that seems to have been accidentally excluded from the U.S. military budget. The submarine, to which you will be confined for about 70% of the game, is somehow a little more spacious than the Pentagon, but equally sterile (talking to people is almost not an option) — and your final destination, a small town on the Tunisian coastline, feels like it’s been recently evacuated (although, for some strange reason, it is still possible to cater for food deliveries!).

In other words, atmosphere as such simply does not exist in the game. Even the «romance» subplot reads like it’s been intentionally transplanted from a «romantic pickup for dummies» textbook (and then is ditched for the rest of the game until the very end, by which time any interest you might have had in «Stacy» must have shriveled after hours upon hours of exerting yourself to death with those submarine controls). It’s as if Walls had so much on his hands that in the end, he only had enough time to implement all that bureaucratic-procedural stuff from his Police Quest experience, diligently describing how you should do all that stuff but completely forgetting to explain to us why you should care about doing it in the first place. Actually, there’s no explanation necessary: you just do it because you’re programmed to do it. For some strange reason, the art of choosing the right color for your Hawaiian shirt and the procedure of making small talk with a lady whom your algorithm prescribes for you to take to bed are not at all discussed in the enclosed U.S.S. Blackhawk Technical Manual. Must have been a technical omission or a limited budget thing.

One could, of course, always turn this around and say, “well, this is the story of a top-class secret agent on a life-and-death mission. What do you want him to do, be able to stop and smell the flowers at any point? hunt octopuses in underwater caves? go out into the Tunisian desert in search of the Little Prince? This ain’t The Witcher 3 or some other open world nonsense like that, you’re on a job and the clock is ticking!” And it is true, there is certainly a sense of urgency in the game — a lot of the sub-missions are on a strict timer, miss it and die — there’s barely even any time to relax back in your Tahiti cabin. But if so, why do we need these exotic locations in the first place? Come to think of it, what was even the point of transporting the top secret agent by submarine half across the world, if not to hunt a couple of octopuses along the way? Couldn’t they have, you know, just flown him into Tunisia as a tourist or something? Nobody really explains the weird logistics...

Overall, given that the «atmospheric» criterion is essentially introduced here to answer the super-important question of «would you want to live in this game’s universe for a period of time?», I think the final verdict is rather self-explanatory.

Technical features

Graphics

From a pure visual standpoint, Codename: ICEMAN is really neither here nor there. All of the studio’s 1988–1990 EGA period games have a conventionally solid pixel-art style which still holds up amazingly well today, even on a big screen, so even if Sierra did not have their top art wizards assigned to the project (Cheryl Loyd and Jim Larsen were relative newcomers who would go on to work with Walls on Police Quest 3), results were still decent and very much in line with the rest of their games from the same period.

Which is also where the main problem lies — graphically, the game does not succeed in establishing its own identity. The opening scenes on Tahiti, for instance, feature lots of cool colors and textures — sea of blue and sky of green, lush vibrant jungle foliage, seductive yellow sands — but it all feels lifted from the second and third Leisure Suit Larry games, where you could experience all the same stuff in far more immersive detail. The modest interiors of the Pentagon feature the same minimalist business look as any official interior in Police Quest. The gadget-filled, thoroughly cramped and overstuffed belly of the submarine feels like it’s got a touch of Space Quest’s Two Guys From Andromeda to it. All of these backdrops can please the eye one way or the other, but there is hardly anything about them that suggests going above and beyond the call of duty.

For honesty’s sake, I can make one exception. There is a sequence in the game in which, after having just spent an hour or so of the most miserable time in your life trying to make heads or tails of those awful submarine controls, the Captain invites you to rise to the surface and climb out of the hatch for a few minutes. The game then transitions to a brief semi-cut-scene with you and the Captain scouting out the Russian battleship on the horizon — with a fantastic psychedelic color mesh of the setting sun reflected on the waters (see the screenshot!). It’s not particularly exceptional for the Golden Age of Pixel Art, but in the overall context of your cramped submarine torment it feels like a brief moment of paradise... then, of course, you have to get down there and spend another hour fighting the goddamn battleship by following red and white lines on the monotonous periscope screen. But for a brief while — a very brief while — you might revel in the idea that perhaps there is something else in this world worth fighting for, rather than the price of crude oil.

Close-up shots, which were at the time pretty much the only possible way of establishing a bit of personality for the game characters, are limited to just a few — I think that your «love interest» / «work partner» Stacy is only shown up close once, and, honestly, there’s not a lot of «personality» in that shot (it’s more of a «hey guys, make me one that’s just as sexy as those you see in Leisure Suit Larry but with a bit of extra muscle on the bone!» approach). Character sprites have two modes: small (default) and mid-size (triggered occasionally, e.g. in the dance-with-Stacy scene), but this is not implemented as consistently as it was, for instance, in Gold Rush!, where you controlled a larger Jerrod inside the buildings and a smaller one on the streets. The sprites themselves are okay, though, honestly, in his Hawaiian shirt Commander Westland is barely distinguishable from a well-toned Leisure Suit Larry. Maybe that was precisely the idea.

Sound

The entire soundtrack of Codename: ICEMAN comprises about 35 minutes of music, which, I guess, is fairly standard fare for the time (only Mike Dana’s brilliant soundtrack for Leisure Suit Larry 3 stands out in this respect, with more than an hour of fully fleshed-out compositions). The music was commissioned from Sierra’s resident composer, Mark Seibert, who had previously worked with Jim Walls on Police Quest 2, and preserves more or less the same style for this game — largely influenced by police drama soap operas and generic action movies, and milking those MIDI synths for suspenseful, spooky keyboard tones and hilariously «tough» MIDI guitar-drenched electrofunk grooves (and a corny romantic interlude from time to time, though more in the elevator jazz than in the power ballad style, fortunately; there was still quite a way to go to the ‘Girl In The Tower’ nadir of the man’s career).

Despite their generic nature and minimal length, these little sound bits are arguably the most significant component in building up the game’s atmosphere, be it the silly catchy dance rhythms of the ChiChi Bar in Tahiti or the «danger lurking on every corner» ambient minimalism of the ‘Tunisian Compound’. It’s all strictly «video game music», no aspirations toward anything more ambitious, but this is precisely why it helps downplay and dilute any of the game’s pretense to seriousness. In all honesty, I cannot say whether Walls intended for the game to send a stern, no-nonsense message of patriotic duty and all, but every once in a while, that message starts seeping through, and Mark’s music does a good job of neutralizing it, reminding you that all of this is just light-hearted pulp, really. (Of course, it’s all a hoot only if you get to hear it in full-fledged MIDI: PC speaker or even a simple SoundBlaster card were probably more of an annoyance even back in 1990).

The game has no speech (still too early for that), which may be a good thing — a very good thing — but it does have plenty of well-processed sound effects, from the waves crushing on the Tahiti beaches to terrorist bullets rattling off during the final car chase. Because of this, the game is almost never completely quiet (unless you bother to turn off all audio), which can get very discomfortable while you’re inside the endlessly humming sub: on one hand, it’s realistic, but on the other, the noise can really get on your nerves while you’re busy dying your innumerable deaths because of your inability to understand or master the barely responsive submarine controls. Worse, the sound effects are there just for realism, never for creating any kind of drama or suspense of their own (for an example of how, in the very same time period at the same studio, sound effects could be used for real emotional impact, check out Conquests Of Camelot). In other words, much like every other aspect of the game, audio is mainly here just because somebody got paid for it.

Interface

Like any other Sierra game from that period, Codename: ICEMAN is based on the original version of the Sierra Creative Interpreter (SCI) engine and features a standard text parser as the main interaction tool between game and player — and when I say standard, I really mean it with my heart and soul. Even the overhead menu is completely stern and minimalist, offering not a single extra perk above the usual fare (save/restore, quit/restart, turn sound on/off, check inventory etc.). The parser works reasonably well (at least, no legendary Larry II-style bugs associated with it), but trying to make the best use of it for immersive purposes hardly ever pays off, because there is really not a lot of stuff you can «look at» or interact with in the game outside of the main storyline (the writers are being quite terse and laconic when it comes to describing any of your surroundings) — not to mention that quite a bit of the time you will simply have to type in instructions from your manual, a pretty excruciating chore when it comes to giving CPR on the beach or selecting the proper washer diameter at one of the submarine’s work benches.

What makes the game seriously different, of course, is the abundance of action sequences and simulators, which is where you are bound to receive the majority of those headaches, especially on faster PCs that are not fully in tune with the game’s original speed settings (and even intelligent emulators like ScummVM cannot always keep up these days). As it often happens in games, the hardest part here is to understand what precisely is required of you — for instance, the submarine switches are unmarked, and the instructions are sometimes ambiguous, so generally I found myself dying due to ignorance rather than poor finger reflexes. The worst part is probably the sequence where you have to follow the guiding sub on the radar, keeping steady on its tail so as not to get lost (and die), or, better, to get a perfect score — the controls for that sequence are anything but intuitive, and I really have no idea how they could be figured out without a hintbook or walkthrough.

The battle sequences are very disappointing: usually, all it takes is understand the correct depth settings for survival (more manual reading), the correct missile type to launch (even more manual reading), and a bit of prayer because there is a random chance of hit-and-miss both from you and your hostile combatants. Read your manual, make sure to save the game at the proper intervals, and watch the black and red torpedo lines overlap with each other on your periscope screen as if this were 1979, not 1989 — gee, fun!

The final challenge — escaping the terrorists in a rickety old van across a winding mountain path — was apparently deemed to be so challenging that, in a rare gesture of mercy, you are offered the option of skipping it altogether. But then, of course, you don’t get the full score, so eventually I had to clench my teeth and go for it. Again, though, it is more an issue of understanding than getting good with your fingers (you really just have to follow a simple accelerate-decelerate pattern for each stretch of the road, not forgetting to do both so as not to get shot down by the bad guys or crash / go over the cliff at each turn), so, unlike the combat sequences, this one bit was actually fun in the end.

Other ways to torture the player include toying around with cryptography, as you have to use a code book to decrypt radio messages (okay for once, but getting a bit mind-numbing as you have to do it at least three times); and a separate screen for the dice game, which is fairly easy to comprehend but fairly difficult to get out of with a positive result (as I have already mentioned previously, this is one of those cases where realism has no place in a computer game). There is also a sequence where you have to use the cursor keys to plot your submarine course by comparing the screen layout to the coordinates on your printed map from the manual — not so much another copyright protection device (though it is) as a trip back to school to do another geography exercise. (Teacher Walls has no patience for slackers.) All I can say is that I respect the creativity — they really tried a lot of different stuff, instead of concentrating exclusively on one aspect — but I’m pretty sure they also saved all the money they could on proper beta-testing. Did Walls ever try to play his own game, for a change?..

Verdict: A glorious failure on all fronts that should never ever be forgotten.

Far be it from me to put this game into the «so bad it’s actually good» category, but «so bad everybody should at least take a look at it» would probably be not too far off the mark. Because Codename: ICEMAN was made at a time when almost all new gaming ideas were actually new, rather than just subtle designer nuances on well-explored mechanics and strategies, it is really quite interesting to look back at even the clumsiest and least exciting implementations of these ideas. Especially since even back then, some of Sierra’s games were already designed according to fleshed-out and rigid formulas — one thing you can definitely say about ICEMAN is that it tries, as hard as possible, to crack the formula from within. Walls’ strict adherence to the «realism strategy» is in itself quite commendable for its time; and if it helped developers and players alike to discern that by-the-book realism was maybe not such a good ideology for a video game, well, so much the better — I mean, you can’t really tell until you give it a proper try, right?

Perhaps the biggest lesson here, though, is a warning to us all about always minding the size of our britches. Although Police Quest was never one of Sierra’s most beloved series, even its harshest critics would have to admit that it was, for the most part, adequate in its combination of player fun and everyday street (and police department) realism, with Walls making good use of his personal experience on the force. But once he got the green light to climb one step higher and apply the same mindset to something he’d never been directly involved in — a spy thriller / heavy-action situation — that same adequacy pretty much flew out of the window, as if Roger Corman had been offered a shot at The Godfather or something. There was no more humor, no more coziness, no more fun, no more proper in-game universe, and most of the people in the game became mechanical dolls with bits of humanity replaced by stereotypical genre properties.

I suppose there is still some sort of soothing romantic vibe about this — I mean, can we even imagine that any major game studio (and by the standards and scopes of 1989, Sierra was a major game studio back then) would offer a retired police officer, with barely any experience behind his back whatsoever, to design and oversee the production of a spy thriller video game? But then again, here’s also your answer to why these things do not happen any more: sometimes your crazy gamble unexpectedly pays off, but more often, it doesn’t. Sometimes you make the wild decision to publish a bizarre action title from a virtually unknown game company — and it becomes Half-Life. Sometimes, though, your wild decisions are just what they are... wild decisions. Which, admittedly, may still attract a bit of wild curiosity in retrospect.

Curiously, there were at least a couple of ideas for potential sequels: one of Sierra’s catalogues supposedly admonished players to “stay tuned for a new chapter in the thrilling Codename: Iceman series“ soon after the release of the original game — and then after Jim had already left, there was a brief period in the early 1990s of toying around with a thematic sequel with a new protagonist, entitled Codename: PHOENIX. Neither of the two projects went anywhere serious, though, and we probably all have a good idea why — though I suppose that in theory at least, superior sequels were possible. The main logistical problem was most likely about how far such a game should deviate from the puzzle-based, text parser / point-and-click adventure game framework, and none of Sierra team players could ever find a satisfying answer to that question, as the studio never really managed to contribute much to the «action-adventure» genre.

In any case, despite hating almost every minute of playing it, I’m still weirdly satisfied that a game like Codename: ICEMAN exists and can be revisited at will with a proper emulator on hand. Bad games that are bad for mindlessly and boringly following established formulas are one thing, but «exotically bad» games that fail while trying to break out of the usual mold at least have a historical and cultural importance — after all, without knowing the bad, it’s not nearly as satisfying to appreciate the good. At the very least, ICEMAN has its own certified place in the history of Sierra On-Line, which in itself is one of the most intriguing and instructive histories of a game studio ever written, so I feel no sorrow neither for the hours spent playing it nor those wasted on writing this review. And wherever you are at the moment, Commander Jim Walls, I salute you — and, uh... may those prices on the world’s highest-grade crude oil be stabilized for ever after, I guess?

Me likes.

One thing about Sierra - as it happened with other adventure game developers like Legend, games were actually developed by several people, even by committee , many times not credited. Al Lowe said in some interviews that he actually had to redo most of the design on the original Police Quest because at first it only consisted of police procedures. I am assuming that PQ2 had also some valuable input from random people, and probably Codename Iceman just did not have that much because most of the team were focused on other games.