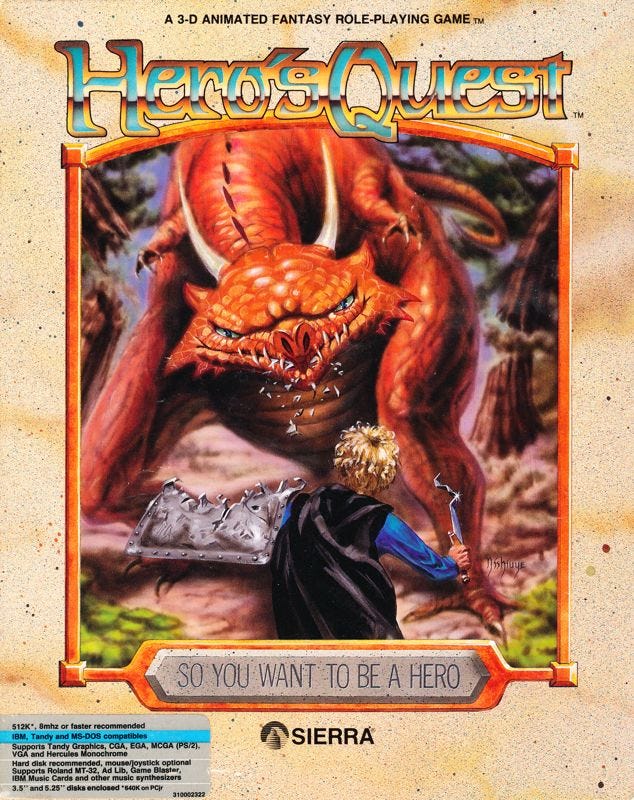

Game review: Hero's Quest - So You Want To Be A Hero (1989)

Studio: Sierra On-Line

Designer(s): Lori Ann Cole

Part of series: Quest For Glory

Release: October 1989

St. George’s Games: Complete playthrough (5 hours 10 mins.)

Basic Overview

It is interesting that in his book on the history of Sierra On-Line, founding father Ken Williams mentions Lori Cole only once, stating that, despite not liking her all that much (on a personal level?), it did not prevent her from becoming one of his favorite game designers — and this rather neatly ties in with the fact that the Quest For Glory series, in which this game was the first entry, eventually became the only series of Sierra adventure games to reach a satisfactory logical conclusion.

Indeed, Lori Cole would be one of the few Sierra veterans, along with Jane Jensen, who would be allowed by their new overlords to complete their projects after the sellout and artistic death of classic Sierra — which, I guess, had not so much to do with the quality of the games themselves as with Lori’s strict work ethics and sense of organization, leaving the industry bosses convinced that she, of all people, would be able to deliver even with the entire adventure game market on the wane. Indeed, Quest For Glory must have been one of the hardest, if not the hardest, Sierra series to properly design; and after all these years, it still stands out as, arguably, the single most «game-oriented» franchise in the classic catalog, as opposed to the rest of its «puzzle-oriented» franchises.

In the early days of its business activity, Ken and Roberta Williams’ Sierra did dabble a little bit in CRPGs, even getting to act as publisher for the Apple version of Ultima II, but none of its proper employees happened to be interested in actually designing a role-playing game — Roberta, the main writer for the studio’s earliest titles, was an avid reader but not much of a dungeon master, and the same applied to almost everybody else. Mainly for that reason, Ken Williams preferred to hold off producing any of his own RPGs until Sierra found a truly experienced DM to work with — and although they never found anybody close to his true ideal, they did hit upon a pretty solid approximation when Corey Cole, a programmer and part-time DM with a decade of experience, came to work for Sierra in order to port its SCI game engine to Atari ST in 1988. This gave his partner (both in the romantic and in the D&D sense), Lori Ann Cole, the perfect chance to pitch a unique proposal to Sierra, and even if, as we know, for some reason Ken Williams never took a serious liking to the person behind the idea, he was still unable to resist the idea itself.

And who would? To this day, Hero’s Quest remains one of the most daring, innovative, efficient, and unparalleled genre syntheses in the entire history of video gaming. By 1989, the aesthetics and mechanics of parser-based adventure games, on one hand, and the aesthetics and mechanics of CRPGs, on the other, had pretty much been set in stone, and were as distinct from each other as, say, heavy metal and synth-pop in the musical world. The main distinction, of course, was that the former were basically interactive fiction — a mostly linear plot which the player had to get through by solving puzzles, immersing oneself in the adventure but not so much in the adventurer. CRPGs, on the other hand, were much less about creative puzzles as such and much more about world-building and stats-juggling, with a focus on your immersion and survival in an imaginary world, based on your own rules, schedules, and general preferences.

To combine both approaches within a single game, so that it might pique the interest of both groups of fans rather than pissing them off, might have seemed like a virtually impossible task to accomplish, but true talent conquers all, or, at least, all those who deserve to be conquered. I can judge by my own example — in my early days of gaming, I was a 100% adventure game fanatic, enthralled by Sierra’s and LucasArts’ unique and individualistic approaches to the crafting of their virtual worlds and generally shuddering at the sight of a typical screen in any typical isometric CRPG game, with its inventories and statistics and clone-like NPCs and interchangeable party members and everything else that made them look less than a magical cartoon and more like an animated game of super-chess. Yet I found myself embracing Hero’s Quest pretty much from the very moment I booted it up (actually, I think I played the later point-and-click remade version first, but my ultimate love still belongs to the parser-based original) — and, in fact, I owe it to the Quest For Glory series for teaching me how to appreciate CRPGs, looking beyond the robotic mechanics and discerning the actual soul inside (at least) the best of them.

The combination of adventure and RPG elements, however, was not the only serious innovation that Lori and Corey Cole brought to Sierra. Hero’s Quest was the first game designed by the studio which was, from the very beginning, conceived as the first part of a multi-part epic journey — and we are not talking here of a «work on Adventurer’s Quest 2 had already begun before Adventurer’s Quest 1 even hit the shelves...» type of situation; we are talking of a series of four titles, representing four different cultures and each corresponding to one of the four elements, etc. etc., that Lori had in mind from the start (along the way, the planned quadrilogy somehow ended up turning into a pentalogy, but that’s just a minor detail). No previous game franchise had ever been organized so diligently — and certainly no previous game franchise offered the player a possibility to save their game stats at the end so that they could import them into the next one, which was not even on the horizon yet — something for which, today, the public usually kindly remembers the likes of Mass Effect, except that Lori Cole did the exact same thing eighteen years earlier.

These and other factors (all of which I’ll be glad to mull over in the following sections) are the reason why, although not a lot of people have played the Quest For Glory series, pretty much everybody who has ever done so seems to have a very fond memory of the experience. Sierra On-Line’s many ventures all have their admirers and detractors, but I have yet to see a directly negative opinion of Lori Cole’s creation (well, some of the five games, like the third one, occasionally get a colder shoulder than other ones, but the average reaction is always positive). The trick was to pull off the first part of the game, demonstrating to themselves and to the public that they could make this mix of adventure and RPG, world-building and plot constructing, seriousness and silliness work its magic on the player. Once this was achieved, the next three or four parts would come more easily — the basic formula would remain the same, but the cultural and atmospheric setting would be completely changed due to the «Hero» being transplanted to a completely different region (think the first and best few installments of Assassin’s Creed, only linked together through the same main character and plot continuity). This ensured that the franchise would be remembered as a strong and consistent multi-part series, rather than a set of individual titles, where even the weaker bits could still be pulled up and supported by the strikingly memorable ones.

While the individual games sold fairly strongly throughout the history of Sierra and earned the studio critical respect as well, the only potential general weakness they had was the RPG-inherited «blank slate» approach to the protagonist — whom, according to Lori’s plan, you, the player, had to shape out according to his chosen class and the choices made along the journey. This means that the main hero of the series — who does not even flash a pre-set hero’s name like «Geralt» — failed to achieve the same iconic status as Roger Wilco, Leisure Suit Larry, Gabriel Knight, Sonny Bonds, or King Graham of Daventry, to name a few of Sierra’s most memorable protagonist figures. And yet, this does not prevent Hero’s Quest or any of its follow-ups from feeling even more personal and intimate than any of those other classics where your protagonist’s personality has been laid out for you in caring detail. That’s the magic of the game, in a nutshell — let’s find out why!

Technical note: The original 1989 release of the first game in the series was called Hero’s Quest: So You Want To Be A Hero, with plans to continue the franchise as Hero’s Quest that had to be scrapped because of a copyright conflict with the board game HeroQuest, also released in 1989. For all the subsequent titles, Hero’s Quest had to be renamed Quest For Glory, including Sierra’s own VGA remake of the first part released in 1992. Since my review will mostly be centered around the original parser-based EGA release, rather than around the graphically superior but otherwise inferior remake, I will continue to refer to the 1989 game as Hero’s Quest throughout, while reserving Quest For Glory to describe the franchise in general. Let’s hope this will not be too confusing.

Content evaluation

Plotline

The challenge set out for Lori and Corey Cole from the very start was a pretty difficult one. Previously, each of Sierra’s franchises carefully carved out its own genre niche, making sure that players would never confuse one with the other (although an adorable line of Easter eggs, sprayed all over the games, used to subtly connect them all together inside a single «Sierra multiverse»). There was King’s Quest for the fairy-tale lovers, Space Quest for the sci-fi buffs, Police Quest for Miami Vice fans, and Leisure Suit Larry for the raging hormones and dirty jokes — under the supervision of Ken Williams, Sierra made sure to establish its presence in each and every corner of the market, utilizing one parser-based game engine to rule them all and in the darkness of your parents’ basement bind them. Life was good and stratified to perfection.

Lori’s pitch of yet another fantasy series, set up in magic lands and centered around a chivalric hero, would be the first to directly overlap with one of Sierra’s niches — and not just any niche, but the «royal» niche of Sierra’s flagman series, King’s Quest, the personal brainchild of Ken’s spouse Roberta Williams, the studio’s primary calling card and, as a rule, also its chief source of income. As you watched your nameless (or, rather, randomly named) hero in his adventurer boots and cape enter the gates of the small town of Spielburg back in 1989, you most likely couldn’t help getting a «King Graham» vibe — oh no, not another wizard-monster challenge — and that might just as well have been one of the reasons for Ken’s distrust of the Coles: diluting and dissipating his carefully constructed edifice by posing a direct challenge to the loyal fandom of King’s Quest that had always constituted Sierra’s main base of support.

However, even if we force ourselves to forget about the crucial difference that could never be overlooked by players — namely, that King’s Quest was a pure adventure series while Hero’s Quest was an adventure-RPG hybrid — it clearly becomes evident that the two franchises are conceived and written with fairly different goals and perspectives. King’s Quest largely acts as a set of fairy-tales, connected to each other through a shared universe, with Roberta drawing her chief inspiration from classic European fairy stories and focusing more on the principal storyline in the here and now rather than on the RPG-essential art of world-building; in addition, most of the games have fairly romantic and/or sentimental plots, and even when they don’t (like the very first game in the series), the plot still borrows heavily from fairy tales in all of its minor developments (like the «perform three valiant deeds to gain the throne» trope is fairly mythological, but Graham’s actual encounters with trolls, witches, and giants all come from traditional children’s entertainment).

By contrast, Hero’s Quest, as per Lori’s original vision, would be based on mythological and pagan lore, taking serious care to properly build up its scenery. The universe of «Gloriana», as it eventually came to be called (though I am not sure if that name actually crops up in any of the games themselves), consists of several distinct regions, each of them dominated by (but not always exclusively restricted to) a certain cultural-historical tradition analogous to one in the real world — thus, the area of Spielburg, as is already hinted at by the name, is depicted largely along the lines of the classic Germanic universe of feudal barons, woodland deities, and heroic rogues, but with moderate admixtures of elements from Slavic (Baba Yaga), Greek (the Centaurs), and other traditions, even already including a «preview» of the next game, based on the Near East, with the Katta’s Tail Inn and its owners and guests square dab in the middle of Spielburg itself.

Likewise, the plot, although it does have a central point — namely, lift the curse off the house of the Baron of Spielburg and reunite him with his long-lost children — is more about a set of loosely connected trials, supposed to test out and shape up the moral and spiritual values of the «blank slate» title character, than about «getting the girl» or «finding your parents» or «rescuing your family» as it is in a typical King’s Quest game. Along the way, said title character — let’s call him Blondie for short, given that you cannot change his appearance and that he hasn’t earned himself any mighty titles as of yet — has to complete a bunch of (usually non-optional) side quests, educate himself on the lore of the land, befriend a variety of colorful characters and, above all, learn to love to live in this parallel universe, embracing both its dangers and its temptations. The universe of King’s Quest was largely there as an entertaining, but pragmatically-oriented backdrop; the universe of Quest For Glory, from the very start, invited you to establish a second home in that location, quite in line with the typical recipe of a typical RPG but buttering the proposition even stronger with its hybrid nature.

That said (we’ll get to the world-building delights soon enough), Hero’s Quest, the first game in the series, actually cares more about making its main plot clear, compact, and concise, than any other one — which is where the relative small size of the location and the shortness of the game can be seen as a plus rather than an unfortunate technical limitation. At the beginning, you, «Blondie», as a newly graduated alumnus of the Famous Adventurers’ Correspondence School For Heroes, arrive in the small town of Spielburg with no specific goal in mind whatsoever other than put your freshly acquired learning to the test and «become a Hero», whatever that means or is supposed to take. Quite likely, your first few hours of gameplay will simply consist of getting your bearings and poking around. Soon enough, however, you begin to realize that there is a very precise mission to accomplish: Baba Yaga, the classic evil demoness from East Slavic folklore, believing herself to be wronged by the Baron of this thoroughly Germanic land, has cast a terrible curse over his household, which led to the disappearance of both his young daughter and son, and the land of Spielburg will find no respite until both children have been returned to their grieving father and the nasty Ogress driven out of the Spielburg Valley for good.

An important observation here would be that, although the character tropes themselves are borrowed from Germanic and Slavic cultural traditions, the actual story is relatively original — in King’s Quest, you usually have a pretty good idea what to do if you have diligently read up on your classic fairy tales; in Hero’s Quest, you are expected to proceed in accordance with issues and solutions thought up by Lori Cole herself, so no matter what you already know about getting rid of Baba Yaga from Russian folk tales, that is not going to help you here. Every once in a while, the plot twists in a surprising manner; you are never quite sure about what to expect from the characters you meet and interact with. At the same time, Lori knows the importance of not overdoing it — Hero’s Quest is not some sort of Monkey Island, i.e. a game where a basic framework of modern values and modern realities is run through an intentionally crude and broken-up «17th century filter» for the sake of humor and parody. What you get is an ever so slightly modernized take (mainly through the influence of Monty Python, on which we’ll comment more in the Atmosphere section) on what could very well pass for an opening chapter in some medieval heroic saga, give or take a few components.

Modern gamers, used to standards set by RPG sprawls like The Witcher or Dragon Age, will probably complain about the plot being so miserably short — indeed, the first game in the series is probably the shortest, and out of its three major «acts» (save the Baronet, save the Baron’s daughter Elsa, deal with Baba Yaga), only the Elsa quest is given full attention in terms of details and challenges. For the standards of 1989, though, I would say that the game’s running length was quite adequate (at least compared to other Sierra games), and most importantly, every single part of the story feels complete: the characters and their motivations are introduced with perfect logic and clarity, and the game’s main conflict — the struggle between the protective, well-meaning Baron and the intrusive «squatter» Baba Yaga — has a slight touch of sentimental dramatics that is neither overlooked nor overcooked, if you know what I’m talking about. And if you take the time to exhaust all possible dialog options with all possible characters (not an easy task in the parser age, where you actually had to think up possible topics for dialog instead of simply choosing them from a menu), you will see that almost all of them have their own personalities — eccentric, haughty, facetious, sarcastic, idealistic, or melancholic; a far cry from the oft-too-robotic presentation of her fairy-tale tropes by Roberta Williams.

This being an adventure game first and an RPG second, Hero’s Quest does not really have any «side missions» per se (i.e. quests completely unrelated to the main story, but rather having to do with world-building and powering up the player), but in order to complete the game perfectly (you can fail at least two of your major tasks), you will need to seek out and interact with a variety of colorful characters — hermits, snow giants, pixies, dryads, eccentric wizards with talking rats, you name it — most of whom will require additional tasks from you, usually amounting to something a bit more than simplistic «fetch quests». All of them are written laconically (again, everybody wrote laconically back then), but vividly enough to enrich the story. And although the story itself does not allow for much branching — except of the alternate puzzle solutions which you do based on your class — you can experience different types of endings, depending on what you did right or wrong.

(Nothing is perfect, though: a poor design choice manifests itself when you come straight to the Baron’s Castle upon rescuing Elsa, expecting to simply get a reward and instead finding out that you have finished the game — without being offered a chance to set things straight with Baba Yaga. Ah well, hope you saved your game and all, as is typically the case with Sierra. On the fair side, I think Hero’s Quest is generally free of random soft-lock situations, though you do, of course, have to be properly prepared if you venture out into particularly dangerous or demanding zones of Spielburg).

That said, the Quest For Glory series is no Game Of Thrones and is not really meant to engage you with the sheer strength of its storytelling; its puzzles, its action, and its atmospheric presentation are far more important than unpredictable plot twists, so let’s move along onto discussing the true strengths of the game.

Puzzles

Every CRPG ever made, on top of its endless combat sequences, stats grinding, and open-world scenery, has something by way of puzzles — and they almost always suck as puzzles, because the rules of the game strictly prohibit the developer from taxing the player’s brain in that manner (most of the player’s brain activity is supposed to be allocated to solving the pressing question of whether it makes more sense to equip the Ice Sword of Mithander or the Fire Halberd of Ur-Guluk to defeat the Legendary Demon of the Sixteenth Underworld). Meanwhile, classic adventure games were designed with a completely opposite goal in mind — and no, the goal was not about «making as much money on additional hint books as possible» (in fact, for a while Sierra actually opposed the idea of publishing separate hint books, and only consented to it after their phone help lines became overflooded with customers); believe it or not, it was really about stimulating the player’s intelligence, even if sometimes the designers did go a little crazy with their moon logic (nowhere near as bad as modern retro-reviewers sometimes make it seem, though).

In any case, Lori Cole was stuck here with a really difficult dilemma — she had to design a kind of game that would be equally as acceptable to two completely different kinds of players as, say, a certain musical piece could be acceptable to opera fans and reggae lovers at once. The RPG elements had to be «authentic», but not too twisted so as not to turn off adventure gamers; and the puzzles had to look satisfactory for adventure gamers, but not too difficult for RPG fans who would not at all be amused typing up commands like «put the airsick bag in the bottle of hair rejuvenator». Would this be manageable at all?

Well, in my opinion, it was perfectly manageable, and, in fact, Hero’s Quest is one of the more outstanding examples of how to do this kind of challenge right — as right as possible, at least, because clearly in this context you are going to accept some compromises, and satisfying everybody is never an option. On the RPG front, Lori adopts the basic tenets of the genre: you select one of the three major classes (Fighter, Wizard, Thief, specializing in brute strength / magic / stealth respectively), you have a bunch of «general» («major») skills such as Strength, Agility, and Intelligence, and a bunch of «specific» («minor») skills such as Climbing, Lock Picking, Attack, Parry, etc., to some of which you can add extra points at the beginning of the game. The nice little trick you can use here is that you can actually add points to skills that are non-native to your class, so if you want to make a Thief or a Fighter capable of casting magic spells, for instance, you are free to do so — or, if you take your coffee black like your men, play it completely pure and rely exclusively on your God-given talents for each specific class.

Grinding your stats in the game can be every bit as excruciatingly (and/or delightfully) masochistic as it is in any given RPG: to raise your climbing skills, for instance, you have to type "climb tree" over and over again until your fingers bleed or you run out of stamina (in the early stages of the game, it’s going to be the latter, but as you gradually power up, it’s going to be more and more of the former), and if you are determined to go all the way and raise a given skill to the top level of 100, it’s going to take a long time (actually, this is one of the points at which the game is somewhat broken: some skills have to be practiced only at specific, and rather random, locations to maximize, and others cannot really be maximized at all without cheating in the debugger mode). But on the safe side, you absolutely do not need to maximize any stats to get through the game — in fact, there are only a few rather basic tasks for which you really need to grind, and even most of the game’s ferocious enemies can be avoided as combat opponents, though do not count on getting a really high final score if you chicken out of tough fights with tough opponents.

One thing that was cut from the classic RPG experience is leveling up: Lori, somewhat reasonably, thought that having your character progress from "Level 1" to "Level n" would be superfluous if you can simply have him increase his stats throughout the game — thus, for instance, your amounts of health, stamina, and (for magic users) mana simply rise in direct proportion to pumping up your Strength, Vitality, and Magic scores by fighting enemies and casting spells, with no need to tie this to the extra procedure of advancing from level to level. A rudimentary trace of that mechanic is the somewhat baffling inclusion of an XP parameter — you do accumulate tons of XP as you go through the game, but the parameter is absolutely meaningless, since in a typical RPG accumulated XP allows you to eventually increase in level; in Hero’s Quest, however, there are no levels, and the parameter becomes a useless atavism. (It would be removed in subsequent games).

Naturally, this kind of «lite-RPG» experience would be laughable to seasoned veteran players of the genre — it’s just the basic arithmetic — but for adventure game fans, unaccustomed to the full RPG service level (like I was myself when I first played the game), it must have felt just right. Everything «RPG-ish» about Hero’s Quest can be easily understood by a total noob in about 20-30 minutes of playing, after which you can just relax and have fun with the game. Even getting upgrades for your armor and tools is a simple process — you can only do this once or twice, as you earn enough money to buy the higher level stuff, and you don’t have to calculate any baffling AC or THAC0 scores to understand what suits you better. All in all, I think that the «minimalist framework» for an RPG experience simply couldn’t have been handled with more intelligence.

The combat system designed for the game did come under critical fire from time to time, but then it isn’t really that much different from simplistic combat systems used in most 20th century CRPGs — at least, you do have the options to attack, parry and dodge, unlike, say, the early Elder Scrolls games where you can only wildly hack away at enemies. In all honesty, though, I found myself using the Parry and Dodge mechanics only with the explicit goal of raising those stats (and the accompanying Major Skills such as Agility), because it is difficult to «read» your enemies’ animation moves — they are simply too fast — and assuming defensive strategies when fighting a Saurus Rex or a Cheetaur is a rather hopeless waste of time. The one thing you really have to understand well in Hero’s Quest is when to fight and when to run from an enemy that is way too overpowered for your current stats. (For that matter, Lori does take care that particularly strong enemies, such as the above-mentioned Saurus Rex and Cheetaur, only begin consistently harrassing you once your overall stats have crossed a certain threshold).

Now, as to the actual adventure content — here, the experience has been somewhat simplified as well so as to accommodate the tastes and habits of any potential RPG fans that might want to try out the game. The «puzzles» in Hero’s Quest are, on the whole, notably simple in comparison to the average «pure» Sierra adventure game from the same time. The actions you have to perform are generally logical; there is no complex manipulation / juggling of several different inventory items to produce the result you need; and the majority of puzzles have alternate solutions, ranging from simple brute force to something more delicate — also, sometimes in order to solve a challenge your main task is to simply raise a particular skill.

For instance, at one point you need to obtain a ring from a bird’s nest. In a typical Sierra game, you would probably have to scour the map for some tools to do it, or think of some tricky way to lure the bird away from the nest (e.g. obtain a woodwind instrument and learn to imitate the bird’s call on it). In Hero’s Quest, all you need to do is raise your climbing skills high enough to be able to first scale the tree trunk and then to move along the tree branch without falling down. Or, alternately, you can raise your throwing skills for a more violent solution and knock the nest down with a rock. Or, alternately, you can use magic and burn the nest down with a Flame Dart. Or, alternately, you can refrain from violence once again and use a Fetch spell to simply retrieve the ring — provided, of course, that your Fetch spell is well-trained.

If you pursue a minimalistic goal of simply beating the game, at whatever cost necessary, you won’t ever need a hint book or an Internet walkthrough — just grinding your fighting, spellcasting, and/or stealth skills will be enough to easily make it through most of the challenges, as I cannot really think of any particularly tough spot to get stuck upon. Of course, if you want the top score and the most «refined» solution to all the challenges (e.g. without having to resort to a lot of violence), this will require a bit more creative thinking, but not a whole lot more. Probably the most difficult segment in the game is at the end, where you have to think quickly and out-of-the-box in order to survive while breaking through to the Brigand Leader in their den — this section might cause some frustration, especially for those who play it on modern computers, due to potential issues with event timing — but even there, it is easy enough to figure out the right sequence through trial and error (you WILL die, though — quite a lot — so, as usual in any Sierra game, save-early-save-often).

Also, as usual, the most difficult thing in the game is to collect all 500 points — to do that, you have to be very meticulous about everything you do, avoid «brute» solutions as much as possible, and, most importantly, exercise your brain when conducting dialog with various NPCs. Most of the time, the game simply awards you points whenever you strike any basic conversation with any of them, but sometimes, a specific question must be addressed to a specific NPC on a specific topic to gain those precious extra points, and without a dialog tree you have to be able to figure out the topic all by yourself. To be fair, there are maybe only two or three spots in the game that require you to do this, but if you miss even one of them, say goodbye to the coveted «500 out of 500»! (No such problem exists in the remade point-and-click version, of course, where the parser has been replaced with said dialog trees — unnecessary frustration removed, some will say with relief; stimulating challenge cut off, others might grumble with disappointment).

Ironically, I have a feeling that it is precisely this intentional «dumbing down» of the puzzle difficulty level, resulting out of the necessity to smoothly hybridize adventure and RPG elements, that ultimately contributed to the Quest Of Glory series being more fondly remembered than any other Sierra franchise — at the very least, it is never quoted for the proverbial «frustration over moon logic» that most of those have suffered from over the years. Apparently, mechanically grinding for stats pisses off less people than having to put airsick bags into bottles of hair rejuvenator — even if mechanical grind makes you sometimes feel like a robot, it doesn’t make you feel like you’re stuck with no options, and being able to do something, no matter how tedious or repetitive, is always better than not being able to do anything. Besides, as I said, merely beating the game requires only a relatively small amount of mechanical grind.

Instead of wracking your brain, Hero’s Quest simply invites you to have fun — such as trying out different solutions for the same problems, which, up until then, has only been an occasional, «bonus» element in some of Sierra’s games, but is implemented here as a core concept of the game. My favorite way of playing, however, has always been a bit «cheatish»: I always roleplay my character as a Thief with more-than-zero Magic skills, which means I can master any skill in the game, cast most of the spells, fight (daggers only, no sword-and-shield), and still be able to rob the entire population of Spielburg (= a whoppin’ total of TWO different households) blind to the best of my abilities. (And if I then import my character into the second game as a Wizard rather than a Thief, I’m pretty much set to explore all the possibilities in Quest For Glory II). I mean, why limit yourself to apple pie when you can have chocolate ice cream as well, right?

Atmosphere

My general opinion is that the measure of success of an average CRPG seriously depends on the way you answer the question: «would I want to live in this virtual world, or at least pay it an extended visit from time to time?». And when it comes to the Quest For Glory series, my answer is almost always un unequivocal yes — meaning that the games actually succeed as an adventure-RPG hybrid. Whereas all the other Sierra games are largely goal-based, meaning that you can certainly admire the scenery but are hardly ever distracted by it from keeping your mind on solving the next puzzle and advancing to the next location, Hero’s Quest is the first one of these that encourages you to simply get lost in your environment for a while and settle into a dangerous, but comfy routine of world-roaming, monster-hunting, tavern-sitting, and stats-building. And somehow it manages to do all this without the advantage of a sprawling open world, but keeping it all limited to just a couple dozen or so screens of explorable space, amply proving that in this situation, size really does not matter.

Much of this has to do with a highly intelligent level of general design. When you enter the Town of Spielburg, you quickly discover that it is very miniaturesque: precisely four screenfuls of outside space, and about 7–8 interior spaces that may be entered (some of them illegally, accessible only to the Thief class): basically just two streets forming a V-shape, one dead end dark alley, and a bunch of tightly clustered houses. Yet all of it feels neat, welcoming, and complete: a tavern, a general goods store, a magic shop, an adventurers’ guild, an inn to spend the night, a couple of cozy dwellings, and even a secret location for a Thieves’ Guild. Compare this to, say, the sprawl of a large town in the likes of The Elder Scrolls: Daggerfall, with its procedurally generated gazillions of similar-looking roads and mass-produced internal environments, and, honestly, I’d rather live out the rest of my life on those two streets of Spielburg, where everything is close at hand and you can expect elements of individual, hand-crafted design in each of the houses you enter, as well as unique, personalized dialog from each of the NPCs you get to interact with (I think there’s about five of them, but each one is worth five hundred mannequins roaming around you in Daggerfall or its ilk). Buying apples from the local food stand, enjoying a brew at the bar, chatting to the Kattas during an evening meal at the tavern, reading the notice board at the Adventurers’ Guild... that’s the life!

Of course, the game is not confined to just the Town of Spielburg: once you step outside the gates, the first thing you are told is that "you are on your own in a very dangerous place", and the warning should be taken seriously. Just as it usually happens in a typical RPG, your first hours of roaming around the place are the most dangerous of all — an underleveled Hero can very easily die in his very first round of combat with a random enemy, even a relatively puny one, so it always makes sense to try and build up your skills as best as possible before leaving the town or its closest outskirts. The forests of Spielburg by daytime are a lovely sight, a delicate mixture of browns-and-greens populated by chirping birds and largely free of «static» dangers, except for one or two particularly troublesome corners. But random enemies pester you quite consistently from all angles as you travel from screen to screen, so be always prepared to run back to the shelter of Spielburg’s walls in case you have not stocked up on health potions (which are rather expensive, and not easily available to you at the start of the game).

Then, of course, there is the day-and-night cycle: at night, the palette expectedly changes to darker, more threatening colors (with quite a sinister effect) and even more threatening enemies, like the nearly-unbeatable Trolls, begin coming out. There are only a couple of side missions you are actually obliged to perform in the forest by night, and both can be put off until near the end of the game — this is to say that the atmosphere does make me somewhat fidgety when I have to explore the forest after dusk, particularly since, I believe, the randomizer works in such a way that your chances of meeting enemies, and really dangerous enemies in particular, seriously increase after dusk, and pretty soon you might see yourself running away in panic from an overpowered Saurus Rex only to run into a Troll just as you think you’re out of danger. The two «safe spaces» placed in different parts of the forest — Erana’s Garden and the Hermit’s cave — feel like a real blessing, especially since you can spend the night there and venture back out in the forest under the protective rays of sunlight.

Appropriately creepy visuals and music enhance the effects of Spielburg’s most dangerous locations — such as the Kobold’s Cave and, of course, Baba Yaga’s hut itself, places rife with death traps and an overall desire not to spend more time there than necessary (even if you happen to kill the Kobold itself). On the other hand, the Brigand’s Lair is designed in such a way that it focuses on the intensity of the situation rather than the death traps — it’s not spooky, it’s just designed so as to kill you as fast and efficiently as possible, requiring quick thinking (which is not as easy as you might imagine, given how typically the game urges you to rather take it slow, relax, and just bathe your senses in the surrounding ambience).

But in addition to the prettiness and the coziness of it all, and the creepiness and suspense, on the other hand, there is a third equally important component in the game: humor and irony. Where the typical RPG usually plays it in a straightforward manner, often getting bogged down in its own seriousness and pomp, Lori Cole had a far better developed sense of humor than Roberta Williams ever did; in particular, she and Corey were big fans of Monty Python, which became a major influence on the Quest For Glory series in its generally successful attempt to cross-pollinate the epic seriousness of the Arthurian legend with the absurdist Monty Python take on it. Humor manifests itself already in your early exploration of the town, where, for instance, the Adventurers’ Guild proudly displays a Moose head among its treasures ("courtesy of Sierra Online Prop Department"), and has a reference to Two Guys From Andromeda slaying another of Spielburg Valley’s fearsome monsters. Humor reappears consistently in the speech patterns of various NPCs, ranging from friendlies (Henry The Hermit = a fantasy variation on the old joke of ‘Henry The Eighth’) to baddies (the Skull on Baba Yaga’s front gate, sort of an ancestral premonition of the much more famous Murray The Demonic Talking Skull in the Monkey Island series). Humor, as befits a Sierra game, accompanies many of your death sequences — the funniest of these, of course, consisting in the fact that you can actually try to grind your lockpicking skills by typing «pick your nose», but you should never try it if your skill is too low, because "unfortunately, you push it in too far, causing yourself a cerebral hemorrhage".

Most notably, though, humor in the game is associated with the eccentric wizard Erasmus and his sidekick, Fenrus the Talking Rat — the Monty Python universe is referenced here directly in the opening scene, when you have to pass the Gargoyle’s three questions test to enter the tower ("WHAT IS YOUR NAME? WHAT IS YOUR QUEST?"), and from there on it’s an unending flood of gags, puns, and unpredictability, some of it brilliant, some of it stupid or tasteless, but overall wonderfully relaxing if, for instance, you had only just spent a miserable morning trying to shake off some annoyingly overpowered enemy in the nearby forest. After a traumatic experience like that, nothing restores the spirit better than a friendly cup of tea, a bunch of silly jokes, and a competitive game of Wizard’s Whirl with the local crackpot enchanter and his sarcastic rodent friend.

Of course, some of those coming over from the CRPG side of the fence might feel undignified under such sudden barrages of questionable humor ("do you know what you get when a Tyrannosaurus running eastwards meets a Tyrannosaurus running westwards? — Tyrannosaurus wrecks!"), highly atypical for the «true» disbelief-suspending role-playing experience where humor is usually either lacking completely, or is very carefully tailored so as to function strictly within the rules of the constructed universe. Even so, the finest creators of alternate universes have always been those with a habit of gently deflating the pomp and pretense (e.g. Baldur’s Gate with its occasional subtle references to various elements of modern pop culture), and Lori’s integration of a Monty-Python-lite sensitivity into her world feels perfect to me. The humor is not being shoved down your throat at every juncture — Quest For Glory is not a LucasArts game — but is confined to specific areas and circumstances, centered around specific characters who act like legitimate «comic relief» and, overall, do a good job of modernizing the atmosphere without feeling completely out of place and time. And, for that matter, I happen to believe that Lori Cole does have a great sense of humor, even if the actual jokes vary in quality and originality.

Arguably (I would say «pretty much inarguably», but you can always find people wanting to argue about such matters anyway), this mix of seriousness and hilariousness would only reach its peak three installations later, with Shadows Of Darkness being the Quest For Glory title par excellence that can in equal parts make you die from laughter or get genuine emotional goosebumps. In 1989, neither Sierra nor, in fact, any other game studio were truly ready for conquering players’ emotions on the level of solid literature or cinema. But they were ready to create a wholesome and generally responsive universe which, despite its small size and technical outdated-ness, still feels vibrant, fun, and intriguing today, even if you load up the original parser-based game rather than the later, «prettier» remake — at least, that’s how I feel about it.

Technical features

Graphics

As I already mentioned, Hero’s Quest was the only game in the series to receive an official Sierra remake — the original parser-based, EGA-graphics 1989 release was replaced in 1992 with a point-and-click interface VGA-level version, which is usually the one that «retro-gamers» load up today (I think that most of Sierra’s later compilations only included the VGA remake, making the original a bit hard to come by, particularly in pre-Internet days). My firm conviction is that point-and-click is always a downgrade compared to the parser, but in this particular case, the remake also provided a rather grating discontinuity, as the second game, also parser-and-EGA-based, never got around to getting a similar remake (well, at least not until the unofficial AGD Interactive remake in 2008 which is a whole other story altogether). In any case, the following comments on the game’s technical features only apply to the original EGA experience; I might try to tackle the remake later, along with notes on other Sierra remakes, in a separate review.

The original graphics team for the game consisted mostly of Sierra regulars (from Jeff Crowe to Cindy Walker, you can find their credits listed in plenty of other Sierra titles), but this was the peak of Sierra’s EGA period, during which the studio consistently produced wonderfully-looking games whose visuals still hold up today — and, additionally, I suppose that the thrill of working on something as «completely different» as Hero’s Quest added to the overall drive of making the game look as stunning as possible. It certainly looks much more detailed and colorful than, for instance, the disastrous Codename: ICEMAN, released several months later. The opening sequence alone, in which a playful blue-scaled dragon arrogantly burns down the opening Sierra Presents announcement, which then transitions into a flaming reproduction of the game’s title, was rather unprecedented-ly creative for its time — and the ensuing animation, featuring the title character cockily pursuing a little Purple Saurus and then, as the title Hero’s Quest changes to the sub-title So You Want To Be A Hero, showing him running away from a large Saurus Rex in total panic, does a great job of deflating the pompousness right from the opening seconds. No second thoughts about it — graphics-wise, this was the most creative and memorable introduction to any Sierra game up to that particular date.

And you do not need to go far beyond the opening shot to realize this is going to be something special. The camera opens on the title character entering Spielburg right at the intersection of its V-shaped couple of streets, facing an elongated building neatly separated into three parts: a permanently closed barber shop, Hero’s Tale Inn where you are probably going to spend most of your nights, and the inaccessible Sheriff office. All form parts of a continuous whole, yet each one has its own style and color — dull brown for the barber, bright yellow for the inn, weird pink for the Sheriff. The windows have different stylings, with the inn being flowery, the Office being covered in official insignia, and the barber shop sporting the usual trademarks of a barber shop. The porch is being inhabited by the Sheriff himself, smoking a well-animated pipe, and his assistant, Otto the Goon, playing with a well-animated yo-yo. There’s just something about all this that instantly suggests a wealth of possible opportunities — even if the streets remain suspiciously empty of any random bypassers.

Compare this, for instance, to the opening images of Los Angeles as pictured in Leisure Suit Larry II: that game’s perspective of L.A. is technically far more huge (at least 10-12 different screenshots of exteriors next to the meager two in Hero’s Quest), but each screenshot focuses on one particular building, most of them quite sparse in design and oddly bereft of people; there are two or three backdrops that suggest a whole lot of life might be happening somewhere far in the distance, but as for you, you happen to be stuck in a weirdly desolate section of the city, pretty much dead on the outside, only displaying signs of life if you start seriously looking for them, like you’ve just been placed in the middle of some Kafka novel. Here, on the contrary, with only two shots and a minimum of animated NPCs on the screen, the team has concocted for you the impression of a quietly breathing, generally welcoming quaint little town, relaxing on a hot summer day. If there’s any trouble waiting around, you’ll have to look for it. It won’t come to you on its own, willingly and obediently.

The major challenge for artists responsible for backdrops was to create the impression of a large, sprawling space — the Spielburg Valley, with its forests, meadows, rivers, caverns, cemeteries, and walled town — while limiting themselves to a budget covering approximately 60–70 screens at most (the entire grid is formally 11x11 squares, but not all of them are filled in). The effect is achieved sometimes through surreptitious measures: for instance, parts of the map are walled off with dense bushes or rocks so that it takes you much longer to travel from point A to point B even if they are adjacent to each other. At other times, it’s just a clever use of perspective: for instance, Spielburg Castle outside the town gates looks like a faraway presence, though it is actually reachable by simply moving your character one screen north. As for the majority of forest-based screens — the ones that function only as transition points, with nothing interesting happening other than a random enemy skirmish — they are similar enough to provide continuity and a sense of natural homogeneity, but are also different enough from each other to make sure you don’t get the typical RPG feel of procedural generation. Each background, no matter how similar, is crafted by hand, rather than consisting of pre-fabricated «building blocks».

Special honors go to whoever designed the day-and-night cycle: although it comes in but two versions (well, «day» and «night», with no transitional phases in between), the night-time palette adds a feel of somber weirdness, rather than merely drowns you in darkness. Walking around Spielburg forest at night almost turns into a psychedelic experience, except it’s a kind of psychedelic experience where you can easily get chewn up by an overpowered enemy. (And I’m not even speaking about what will happen if you eat some of those magic mushrooms at night...). Interestingly, Erana’s Garden, the single most colorful place on the map, has its rainbow-like effect completely unchanged regardless of whether it is day or night — perhaps to place additional stress on the supernatural exclusiveness of this charmed location.

Next to the exteriors, interior decoration is not nearly as seductive, but there is actually not a lot of it in the first place, as if the designers intentionally allocated 80% of the graphics budget to illustrate the wilder areas of Spielburg rather than its meager traces of civilization. For instance, you never properly get to visit the Castle — there is only one screen of the main audience room, around which you do not even have any agency — and not a single other building consists of more than one internal screen (sometimes there are additional doors, but you can’t get inside them anyway). Only the Brigand Lair is presented as a complex of oddly meshed courtyards, mess halls, and trick rooms, but I wouldn’t call any of those brilliantly designed, and even if they were, this is the «intense» part of the game where you will mainly have to concentrate on immediate issues of survival, rather than contemplate the scenery.

Pixelated character sprites are generated and animated up to the highest standards of 1989 — they might not look too realistic, but they are distinctive, and the pixels do convey a certain amount of emotional diversity: for instance, Otto the Goon and his compadre Crusher belong to the same species and share the same body proportions, face contours, etc., but the former always has a silly, happy smile on his face (even when he is trampling on you if you bumble your break-in into the Sheriff’s house), while the latter has a consistently and unmistakably menacing expression. And the design of Baba Yaga’s sprite (green eyes, flowing white hair, bushy eyebrows, one white pixel representing one tooth in an appropriately toothless mouth) deserves special appraisal as, perhaps, the most successful attempt at depicting a sinister presence in a Sierra game up to that moment, even if it’s hardly all that impressive in retrospect.

Typically of Sierra, the game does not feature any cutscenes, and NPCs regretfully lack full-portrait-style representation even when holding conversations (at the time, such ruthless expenses were mainly reserved for products supervised by Sierra’s reigning queen Roberta Williams, such as The Colonel’s Bequest). However, you do get animated close-ups of yourself and your enemies in combat, which certainly helps increase terror and tension (Cheetaurs, Trolls, and Saurus Rexes all look quite scary), and there are at least a couple nice «transformational» sequences at key points in the game’s plot which also help out quite a bit with immersion. On the whole, though, it would be quite a while before the dramatis personae of Quest For Glory would start getting all the graphical assistance they really deserve.

Sound

In order to bring the game to life through aural means, the Coles had to fall back on Sierra’s chief composer-in-residence, Mark Seibert — probably not the most talented musician to ever work for the studio, but always a steady and reliable presence with a good knack for understanding the designers’ needs and the essential spirit of the game. Thus, the soundtrack to Hero’s Quest consists of about half an hour of relatively short vignettes that expectedly range from the «generally epic-heroic» to the «medieval / folksy» to the «facetious / hilarious», faithfully reflecting Lori’s triple inspiration of generic D&D themes, European folklore, and Monty Python.

The main ‘Hero’s Theme’ (or ‘Quest For Glory Theme’) arguably became one of Sierra’s most recognizable ditties — even if, melodically, it is very much a fanfare-style pastiche of John Williams’ Indiana Jones theme, mixing a formal epic flair with humorous braggadocio. (Considering that Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade was just making the rounds at the time, the influence might have been almost inevitable). I wouldn’t say it is an absolutely perfect fit for the game, because, unlike Indy, your title character does not really have all that much himself by way of personality — not only is he a blank space, he is a mute blank space, being almost as much a passive observer of the bubbly atmosphere of Spielburg as you are on your own. But then again, it’s difficult to imagine what would have been a perfect fit, so let’s just roll along with the flow.

Most of the other themes are less catchy, but work wonderfully as just the right kind of incidental music to sharpen your impressions of whatever is going on. A humorous music-hall theme accentuates the «comic relief» aspect of the ’airy ’Enry The ’Ermit in his lofty cavern. A joyful, bouncy polka that will have you whistle along in no time accompanies the presence of Yorick the Jester relieving the life-threatening tension in the Bandits’ Lair. A mystical waltz gives stately dignity to the otherwise naughty frolicking of the pixies in the Mushroom Meadow. A walking jazz bassline with threatening saxes gives your thieving break-ins into other people’s houses the feel of some 1950s’ caper movie. A Mid-Eastern theme greets you in the Katta tavern, church organ predictably haunts the graveyard at night, and the classical guitar serenity of ‘Erana’s Peace’ almost awaits a Joan Baez or a Sandy Denny for a guide vocal (but no, thank you). And while I cannot say for sure if Baba Yaga’s theme was actually influenced by some nightmarish Scriabin piano piece or not, I think that Mark was aiming here for a bit of that «Russian take on Bald Mountain» feel in general (actual Russian folk music is rarely scary enough, so you still have to look for inspiration from the likes of Mussorgsky or Scriabin).

All in all, despite the overall brevity, the Hero’s Quest soundtrack is one of the better ones from Sierra’s early soundcard / Roland MIDI years, and perhaps even the best one out of all those commissioned from a composer-in-residence (though it still cannot compete with those commissioned from outside professionals, such as William Goldstein for King’s Quest IV or Mike Dana for Leisure Suit Larry III). Additional sound effects, unfortunately, are rather limited — but at least there’s plenty of birds chirping around the forest, or occasional spooky odd sounds a

t night, helping the environment come to life. (No speech, unfortunately — the NPCs of Quest For Glory did not gain the gift of spoken language until the fourth game in the series, which is very much a pity).

Sound-wise, I think the best aural snapshot of the game can be captured right at the start. The (wannabe) Hero struts into the peaceful, relaxed town of Spielburg on a hot summer day. The unseen birds accompany his arrival with bouts of lazy chirping. The brutish-looking, but amicable Goon is swirling his yo-yo in a clock-like manner, symbolizing that there’s so much more to life than monster-hunting and crime-fighting. And the ‘Hero Theme’ is very, very quietly whistling away in the background like a reprised echo of its bombast you just heard in the introduction, suggesting that.. well, maybe just that it’s a long way to the top if you wanna rock’n’roll, no? There’s just something alluringly confident, ironic, and relaxing about that kind of combination at the same time — quite a subtle sonic allure for the standards of 1989.

Interface

To match the hybrid nature of the game, the Coles needed to introduce quite a few significant changes to the traditional Sierra game engine and interface — although it does warm my heart that, instead of starting over from scratch (for which they did not have the budget anyway), what they did was simply take the classic parser interface and expand it with additional RPG-style options. For the most part, you are going to do exactly what you usually do in those Sierra games — walk around with the cursor keys and type in verbal commands. But you also have an additional piece of interface to assist you — the Stats screen — and you have a special Combat window whenever you find yourself attacked, with the ability to use cursor keys for attacking, parrying or dodging your opponents, a mechanic that could occasionally crop up in another Sierra game from time to time, but only in Hero’s Quest becomes a major part of the show.

Everything is smoothly designed and intuitively obvious; the only complaint, perhaps, is that the Coles forgot to properly map out any options to function keys — thus, in order to grind your climbing or throwing skills, you will have to type in climb, climb, climb or throw, throw, throw until your fingers go blue (luckily, the F3 key still works in the usual Sierra «repeat last command» mode). Likewise, in combat you will actually have to type in cast Flame Dart to magically harm your opponent which — dare I say it — does somewhat break the immersion, and this is coming from one of the last remaining Defenders Of The Parser in this fallen point-and-click universe. (Then again, remembering the convoluted command system of something like Ultima V from the previous year, I’d say that Hero’s Quest gets off pretty lightly).

The parser works reasonably well, even if, looking under the hood, you can discover quite a few lines of dialog that do not seem to be triggered by any possible command — most likely, due to buggy programming — and, as I already mentioned, exhausting all possible dialog topics with characters is quite a challenge (but not an unreasonable one). As for the «action» part of the game, well... the combat system is tolerable if you do not waste too much time on trying to figure out the perfect combination between offense and defense, and end up simply hacking away at weaker enemies and staying away from enemies that you cannot properly handle as of yet. The most «unusual» of all is the stealth mechanics: in a typical modern RPG we usually expect a good stealth level to allow you to creep up on enemies without being detected, but here increasing your stealth points mostly just leads to decreasing the probability of encountering a hostile presence on the next screen you enter. (Also, it’s damn hard to raise stealth — at first, you can do this by simply sneaking around from screen to screen, but eventually you only begin gaining stealth-related XP by triggering «enemy-avoiding» situations, so if you’re really anal about grinding up to the maximum 100, prepare to waste hours of your time in the worst manner possible).

I also do believe that most, if not all, versions of the game were among the first Sierra product to leave in the «debug mode», even if it was obviously not announced in the game manual, and unless you knew how to crack the code (but then why would you even need a «debug mode»?), nobody would ever guess that typing in razzle dazzle root beer would give you easy access to tweaking all your stats, as well as a lot of other options. With the arrival of the Internet, of course, it did not take too long for the secret to spill out, and now only the most loyal roleplayers would want to honestly grind for those stats.

In all honesty, though, you don’t really need to grind for high stats — first of all, you can pretty easily beat any challenge if you raise them over 50–60 points on the average, and second, it is much easier to compensate for your shortcomings after you import your character into the second game (where the skills respectively peak at 200 rather than 100 — then at 300 for the third game, and so on). And yes, at the end of the game you were diligently offered the choice to save your character stats into a separate file which you could later load at the start of Quest For Glory II. Neat!

Verdict: A promising start for the single best RPG-adventure hybrid franchise in history.

If there is one glaring flaw about Hero’s Quest, and the entire five-game franchise in general, then I’m happy to say that it actually starts to glare long after the initial period of excitement about stepping into the shoes of the newly established «Hero Of Spielburg». For all of its brilliant design choices, inventiveness, originality, and humor, the game does not offer much by way of substance. Your «Hero» starts out as a blank slate — and pretty much ends as a blank slate. He is unable to talk; any plot choices he has to take or moral dilemmas he has to solve are usually limited to «to kill or not to kill»; and even the slightest, most trifling and short-lived NPC that he meets on his travels has a more memorable presence than his own pretty face. On top of that, though, all of said NPCs are ultimately clichés of the genre; and the overall message of the entire story is a straightforward «save the world from evil and go home», without any deeper implications. (Well, I guess there may be tiny buds of a family melodrama trying to break out of the clearly uneasy relationship between the widowed Baron and his children, but most of the actual sprouts are left to your imagination).

Naturally, compared to more modern, multi-dimensional takes on the same subject — The Witcher obviously springs to mind — Quest For Glory feels like a pretty primitive effort. But then, after all, it is a game, not a movie or a book, and like all good games do, what it lacks in terms of intellectual or emotional substance it is supposed to make for by way of immersion and engagement, and on this front, it is a brilliant example of achieving an ambitious goal through very modest, laconic means. For the first time in Sierra history, a game was made that made you not just want to beat it, but actually live inside it for a while — exploring, admiring, fighting, resting, training, talking, taking your time to prepare for a challenge rather than rushing into it head first; and all of this without that nasty mechanical residue that often lingers in your head after a session of playing some sprawling, procedurally generated RPG.

As for depth and complexity... well, you know, sometimes we deserve a break from depth and complexity. As much as I love the Witcher games, not everything needs to be sprawling, politically convoluted, and bathed in fifty shades of black-and-white as you are forced to choose the lesser of two evils and all that. (We make those choices in our real life every day, so sometimes it’s nice to be able to simply stick to the Absolute Good, you know, at least in virtual reality). And Hero’s Quest offered us that possibility with much more subtlety and intelligence than, say, the average King’s Quest game, which usually featured far more stereotyped NPCs, far more predictable and linear plot twists, and far less engaging humor. In addition, the first game was just the start: soon enough, «Gloriana» would begin expanding on all fronts, soaking in even more cultural references, offering even more choice opportunities, and even, at its best (Shadows Of Darkness), providing that much-necessary emotional pinch when you most need it.

Ultimately, there is a fine lesson in So You Want To Be A Hero for all game designers, especially those modern ones who seem to think that a gigantic open world, in which the player might get lost for years, is somehow a precious value all by itself: no, sometimes less is actually more, and there is something to be said about a small, cozy environment which you can call your home, as opposed to endlessly scrolling locations through which you always go as a tourist. Especially if that environment integrates a bit of heroism, a touch of whimsy, and a pinch of humor into its adorable scenery. Just don’t drink the Dragon’s Breath at the tavern, and life will always be beautiful in the Valley of Spielburg!