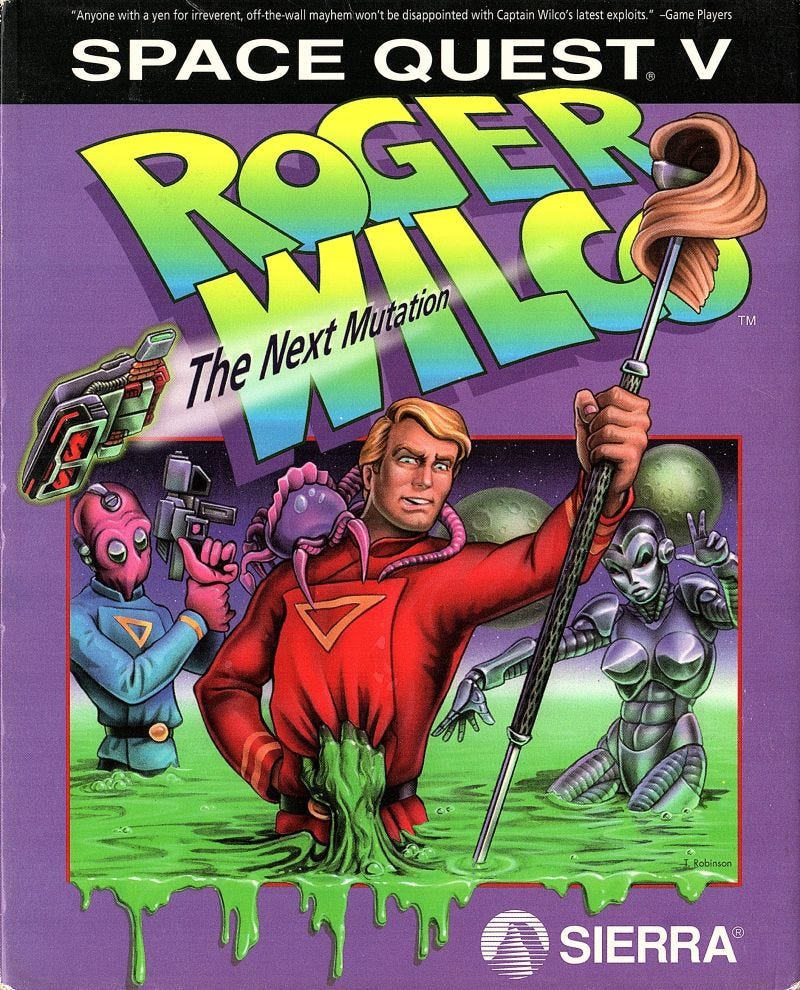

Game review: Space Quest V - Roger Wilco The Next Mutation (1993)

Studio: Sierra On-Line

Designer(s): Mark Crowe

Part of series: Space Quest

Release: February 5, 1993

St. George’s Games: Complete Playthrough Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5

Basic Overview

By 1992, the Two Guys From Andromeda were no longer a working reality. In 1990, the ever expanding Sierra On-Line had purchased the smaller video game company Dynamix, which it was able to lead into a small golden age of its own (with well-known titles such as the flight simulator Red Baron and the wonderful constructor puzzle of The Incredible Machine). In the process of merging and restructuring, however, Mark Crowe somehow ended up in Eugene, Oregon, working on Dynamix projects instead of Sierra proper — yet somehow, he also managed to take the obligation to produce the next Space Quest game with him. Space Quest V is, therefore, a unique project not only in that it was the only Space Quest exclusively designed by Mark without Scott, but also in that it was the only adventure game in a classic Sierra series to be designed and produced outside of Sierra itself — which most certainly left its mark on the game.

All of this seems like a recipe for disaster, but it probably helped that creative juices were bubbling high at Dynamix around 1991-1992, and Sierra itself was also coming out of its rather wobbly transitional period from parser to point-and-click. Crowe himself found a talented working partner in the face of David Selle, one of the leading designers and writers at Dynamix, and together they actually wrote a plot for the game which, while far from being totally original, reintroduced intrigue and tension that were largely lost with the previous game in the franchise. Among fans and critics, Space Quest V is often called a direct parody of Star Trek; this is only partially true, because while a lot of the details do indeed spoof characters and plotlines from the Trek universe, there are also plenty of references to other sci-fi sources, from Alien to The Fly, as well as inside jokes reflecting on Space Quest’s own history. Most importantly, though, Space Quest V does feel like a fairly wholesome and well-integrated chapter in the story of Roger Wilco, so even if it does tend to be more explicitly parodic of classic sci-fi, fans of the Space Quest series should still have no problem accepting everything in it as «canon».

That said, even though the game was a modest commercial and critical success upon release, it has not really gone down in history as a classic: unlike King’s Quest VI or Larry VI or Quest For Glory IV, its contemporary competitors all of which still feature prominently on various lists of best adventure games of all time, I never ever see Space Quest 5 in there — most likely because of those two stigmas that became attached to it, namely «how can a Space Quest created by only One Guy From Andromeda be any good?» and «how can a game whose chief goal is to parody Star Trek be any good?». This attitude seems a bit unfair and prejudiced because, after all, Mark Crowe and Scott Murphy aren’t exactly John Lennon and Paul McCartney; also, Sierra’s history in the early 1990s showed that it actually often helped to bring in new blood for working on established series, e.g. Jane Jensen’s involvement in King’s Quest or Josh Mandel’s writing for Laura Bow. This is not to say that I want to be controversial and declare this game a forgotten masterpiece; this is simply to say that I had a lot of fun playing this game when I was young, and almost as much fun replaying it upon reaching middle age. So let us take a closer look at its various aspects — to provide specific evidence for that final verdict.

Content evaluation

Plotline

Unlike Space Quest I, II, and IV, where Roger Wilco got into the middle of hot action right from or almost right from the get-go, Space Quest V prefers instead to follow the Space Quest III model and take its time. At the beginning, Roger Wilco is a part-time student, part-time janitor at the StarCon Academy (obviously a spoof of the Starfleet Academy), failing miserably at both tasks, yet still having Lady Luck at his side when a malfunction in the system ultimately leads to his appointment as captain... on a garbage scow, of course, because how else would we be able to justify even more of those janitor jokes? Regardless, the exposition unwinds at a leisurable pace, as Roger experiences several run-ins with the game’s principal antagonist (Captain Quirk — har har!) and his future love interest who had been foreshadowed in Space Quest IV (Ambassador Beatrice Wankmeister — hee hee), cheats on his tests, mops the floors, and just generally wanders about the Star Trek and Star Wars references-riddled corridors of the Academy. Even after boarding his new ship and getting to know his merry, racially (or, more accurately, specially) mixed crew, a certain amount of time is spent simply cruising around and getting into random bits of trouble before the game’s main mission becomes clear.

Much like with Space Quest III, I really adore this model. A lot of time and care is invested into fleshing out this new version of Roger Wilco’s universe before the main story begins to distract us from it, yet the story eventually materializes, and the last several acts of the game significantly raise the stakes on action and tension, just like in a good Trek episode. All the early-appearing characters have enough dialog and charisma to them for you to actually care when they find themselves in jeopardy (like Cliffy the Engineer floating in space or Beatrice frozen in cryostasis), and there is enough freedom of movement to soak in the atmosphere of both the Academy and outer space (unfortunately, once you go out there, the designers made it so that you can never return to the Academy again — probably one of those budget things).

The main twist of the story — saving the universe from a failed genetic experiment whose results infect people with a terrible virus and turn them into «pukoids» — is hardly original, but it is well executed, with a bunch of unpredictable plot devices, a couple jump scares, and well-thought out juggling of action-packed sequences and periods of leisurely respite. And since the game is relatively long for its age (at least two or three times as long as Space Quest III), it feels almost surprisingly complete and satisfactory, making good use of all of its characters (even Spike, the cuddly alien face hugger!).

Precisely one turn in the story left me with an ambiguous feeling — the sequence in which Roger is chased down by a female droid bounty hunter and has to concoct a plan to annihilate the threat. Although, on its own, the sequence is well realised, and the underlying two-part puzzle is clever, this is obviously merely a slight twist on the similar story in Space Quest III, which gives you the unfortunate impression that the authors may have run out of ideas and have to resort to pilfering past legacies. Given that the game has no other instances of such blatant self-plagiarism, I assume that the character of W-D40 was intentionally written in as a self-homage, as well as a funny «tough girl» take on the oh-so-very-masculine character of Arnoid the Droid, maybe even as a parody on the slowly increasing ratio of powergirl fighters in pop culture. Yet the intuitive feeling is still one of fan service: «we know y’all are still pining for Space Quest III, so here’s something for ya that will really make you feel like you’re back in Space Quest III». I have nothing against the character of W-D40, and later on she makes a great addition to the crew, but that initial encounter could probably have been handled better.

Speaking of Trek, it is impossible not to mention that one episode here is well known to be a direct homage to the classic Trouble With Tribbles, replacing the original fast-multiplying furry creatures with dehydrated Space Monkeys and reproducing the Scotty vs. Klingon fight with a hilariously inverted twist from the original ("but captain, he called the Eureka a garbage scow!" — "Cliffy, the Eureka is a garbage scow!"). The entire episode is an excellent example of a creative, as opposed to unimaginative and boring, exploitation of a borrowed trope: if you are not familiar with any of the game’s influences (and, not being a genuine sci-fi buff, I am sure that I have missed many of those myself), you will probably never suspect of their existence, so well do the writers work around that material.

Space Quest V also marks a first in introducing a romantic aspect to Roger Wilco’s personality — and, unlike the rather clumsy and corny romance in the next game, handles it relatively well: Roger predictably starts out as a dork in the presence of his new passion, then gradually works out a heroic attitude as circumstances require some damsel-in-distress-saving action. There is very little explicit romance, actually, which is good (the comedy angle should always come first in a Space Quest game), but Roger’s conversations with Beatrice in the cryo chamber still manage to create a bit of an intimate atmosphere around the general chaos, and do not at all feel out of place.

Overall, I would probably rank the plot of Space Quest V as second-best in the series — and if duration, detalisation, and dialog are taken into account as primary factors, it might even beat out Space Quest III (I just do not think it would be completely fair, given the huge changes in gaming technology, stylistics, and aesthetics that took place between 1989 and 1992). Although, every once in a while, it does tend to reduce its title character to a bunch of Roger Wilco stereotypes, it more than compensates for it by giving Roger some much-needed extra depth; and, unlike Space Quest VI, it does not spend approximately 90% of its running time trying to shove the «Space Quest Legend» into your throat and make you chew on it, trying instead to expand on that legend and make the Space Quest universe an even better place.

Puzzles

By the time Space Quest V came around, Sierra designers had largely managed to eradicate their classic issue of «puzzle deadlock» — being unable to complete the game after a certain checkpoint because of having missed some action or object earlier — and Space Quest V, too, goes relatively easy on the player, since after leaving the Academy Roger and his ship operate in a quasi-open world environment, being able to freely move from planet to planet (and pick up forgotten stuff at any point where it was forgotten). However, the other classic issue, Death Around Every Corner, has dutifully not been fixed — much to the fans’ delight, because few of Sierra’s deaths are as classic as Roger Wilco’s, and Space Quest V does not disappoint (that said, most of the deaths are almost boringly logical and predictable).

As far as complexity is concerned, the puzzles of Space Quest V will hardly raise much concern. Arguably the most «puzzlish» episode is Roger’s above-mentioned escape from the droid gal, whose solution is nicely and subtly hinted at during our guy’s test session at the Academy — but whose difficulty mostly lies in correctly figuring out the sequence of your actions. Other than that, there is really not a huge lot of thinking you got to do to beat the game: much more of your time will be occupied by reading, pixel-hunting, oh, and battling some of the game’s unfriendly arcade sequences.

Unfriendliness of the latter has, unfortunately, become exacerbated with time, as some of the things you have to do are directly tied to CPU processing speed and become ridiculously hard or just plain ridiculous on more powerful computers — for instance, early in the game Roger has to use a Scrub-o-Matic Floor Scrubber, moving it all across the dirty floor; on modern PCs, the machine zips through the screen at light speed, making it almost impossible to effectuate any control. Even worse is the sequence in the middle of the game, where you have to rescue your engineer from floating in outer space by pursuing him in a pod and grabbing his body with a mechanical arm — the time you have to do that is limited by your oxygen supply, and it is downright impossible to perform the task on anything higher than a good old Intel 80486. (Fortunately, running the game with DOSBox solves most of these problems in the modern age).

Other distractions are not nearly as detrimental from a technical side, but can also be questionable in terms of the fun factor. Thus, at one point you are forced to play a game of «Battle Cruiser» with Captain Quirk, which is every bit as fun to play as your regular Battleship — the only piece of good news is that Dynamix has not trained the AI even one little bit, so, unless you are exactly as stupid as your untaught computer opponent, you have absolutely zero chance at losing the game (but it will still take a long time to explode all of Quirk’s ships, so gird thyself with patience). At another point, you shall have to navigate a maze (of course!) of ventilation and elevator shafts inside a giant spaceship, with absolutely no indication of where to go and more or less random chances of being squashed by a moving elevator every once in a while. Finally, there is a minor reaction-based sequence which might just gross you out in Resident Evil-style fashion, but at least it only requires you to press the left or right arrow buttons three or four times, nothing more. (Still was enough to give me nightmares back in my impressionable childhood!).

As usual, a few of the actions / puzzles are optional (you have to perform them to better your overall score); the only one of these to earn my indignation is the requirement to cheat on your StarCon Aptitude Test instead of having to solve it on your own. Considering that the Test itself is quite hilarious ("To ensure that your crew’s microwave meals are heated adequately you should: ... [e] inject a radioactive plutonium isotope into each piece of food: when it glows, it’s ready"), but perfectly solvable on one’s own, I’d have thought it would be more just to give you more points for solving it rather than for cheating on it... but, apparently, the designers have such a high opinion of their players, they think that coming up with a cheating scheme would be below their adventure gamer’s intuitive morals. And who knows, maybe they were right about that, too.

Atmosphere

Playing Space Quest V actually feels good. The introductory part, at StarCon Academy, is not all that great because you are severely limited in space, confined to just walking around a small rotunda with a bunch of scripted events in rooms which you cannot properly explore. But once you get out there, Space Quest V brings back that actual feel of, well, space that was so well done in the third game, yet all but forgotten in the fourth. You navigate from planet to planet, watch them come into or fade out of orbit, interact with other ships, even engage in a couple of tense stand-offs — all in all, spend almost as much, if not more, time in the deep dark void as you do on lush green planets. And while there is really not a lot to do with your ship controls, at least you really do have a proper control interface once again, making you feel in charge and genuinely responsible for the life and well-being of your morally ambiguous crew members.

Speaking of crew members, this is the first (and last) Space Quest game ever where you will spend much of your time with company on your hands — the Eureka, your trusty garbage scow, starts out with three crew members (Weapons Officer Droole, Com Specialist Flo, and Engineer Cliffy) and eventually gets even more populated, which implies the possibility of a whole lot more dialog than in the previous games, where Roger mostly used to go it alone (you still do whenever you go on a planetary exploration, but back on the ship, your crewmates always got your back, or at least pretend to). Most of the dialog is played for comedy — Droole showing off his first-rate nihilism, Flo gradually developing a crush on you, and Cliffy making it his life’s purpose to avoid any difficult or dangerous tasks — but each character is quite well written for 1992, with tons of personality and charisma that make you explore even the least useful options on their dialog trees (Droole: "You’ll have to excuse Flo. She has a bit of a problem dealing with male authority figures, but she’s really not so bad once you get to know her" — Flo: "Can it, lobster boy!").

This is probably one of the biggest stylistic departures from the previous games, where it was almost always «Roger Wilco Alone Against The Countless Dangers Of The Galaxy»; the most company you ever had on your ship was a droid co-pilot (well, the Two Guys did briefly join Roger at the end of Space Quest 3, but you didn’t even have time for a proper conversation). Given the abundance of contacts at the StarCon academy as well, or the far livelier atmosphere at the Space Bar than at Monolith Burger, it feels as if the Space Quest universe has finally become a more colonized, civilized, and even safe space — which is, in my opinion, a welcome change from the endless space jungle-braving affairs of the previous games.

The other big departure is the introduction (under the influence of all those sci-fi shows and movies) of genre elements which were previously not on the Space Quest list at all — namely, action and horror. Although you did have to do a bit of space fighting at the end of Space Quest III, it was nothing compared to the lengthy stand-off between the Eureka and the Goliath, where you have to organise the defense, plan the evasive action, and then, in the middle of the stand-off, dash off into space to rescue your careless engineer. This time around, saving the universe requires almost as much flash and brawn as it requires stealth (Roger’s traditional weapon), which seems good to me, provided there is no side effect of actually turning the whole thing into an action game (and there is none).

The addition of (body) horror elements is more questionable. Previous Space Quest games did not really make a point of grossing you out, at least not until it came to all those gruesome death scenes (and vivid textual descriptions of them) which you were guilty of yourselves. Here, once the main plot takes off, nastiness — depicted quite vividly and graphically, might I add — becomes an inescapable part of it, even if you yourself manage to avoid all the death traps. Opinions will most likely be divided on whether this choice contributes to the quality of the game or detracts from it. One certain thing is that, along with the accompanying story of corporate corruption and catastrophic bioengineering decisions (à la not-yet-existent Resident Evil), it gave the game a facelift in the «more serious» direction: every now and then, you get to almost forget that the whole enterprise is a parodic spoof, only to be reminded of it at the least appropriate moment (for instance, at the very end of the game when, in a climactic sequence, the W-D40, with a battle cry of FREEZE SCUM!, begins shooting liquid nitrogen at the infected Goliath crew out of her metallic tits).

In the end, though, I don’t think I have a problem with that. Maybe it makes the game less suitable for really young players (like, anybody under 8 years of age), but I think that the horror elements serve to sharper emphasize the humor — enduring the pressure of Droole and Flo’s authority-debasing jokes upon having just escaped the threat of being «puked to death» somehow feels more fulfilling after the ordeal. Besides, what might have looked genuinely terrifying in the early 1990s now feels like innocent childplay after the Golden Age of Survival Horror; other than one or two small jump scares, there is hardly anything here to leave a lasting disturbing impression on the player. There is enough, though, to make the game feel significantly different from all the previous Space Quests without betraying the quintessential spirit of Space Quest, and this is what makes it such a fresh and admirable entry in the series.

Technical features

Graphics

Space Quest V was not released during any particular graphic revolution, but the fact of its being developed at Dynamix rather at Sierra proper certainly resulted in a stylistic change. The art director for the game was Shawn Sharp, who had previously worked on the more kid-oriented Adventures Of Willy Beamish, and before that, in the comic industry; Mark Crowe, despite having been responsible for most of the art in the previous games, was too busy designing the story to continue working on the game’s art, though he most likely gave some directions and supervised the game for artistic compatibility with the «classic» Space Quest universe — which is why, in the end, the stylistic changes did not so much reveal themselves in the actual art as they did in the general approach.

Thus, when you look at most of the backdrops — the interiors of the StarCon Academy, the space fields, the lush landscapes of several of the visited planets — what separates them from Space Quest IV is mainly an increased attention to detail, from shadows to small cracks to tiny rocks and plants peppering the screen in a more consistent manner than before. But it does not matter a whole lot, to be honest. What does matter is that, in an intentional struggle to make the game come more alive before your eyes, Sharp includes a whole lot of (usually animated) close-up images during character interaction. Never before in a Space Quest game have you seen Roger Wilco that up close so many times, with so many different emotional states on his face — or, for that matter, never before have you gotten a chance to see almost all of the side characters in close-up perspectives (one of the very first images to come up on your screen is, in fact, the huge mug of the dashing Captain Quirk, whose facial features formally match those of the stereotypical Hollywood action hero, but whose expressions clearly betray him as a major villain from the start).

It does not always work exactly the way the artists (probably) expected: for instance, Roger’s new passion, Ambassador Wankmeister, looks hip and sexy (a bit Sharon Stone-like, which is hardly a surprise given that Basic Instinct became a hit in 1992) in one screenshot, but rather plain and whiny in another — I suppose that there were at least several people working on the graphics at the same time. Still, what matters is not necessarily the quality of the images (no masterpieces of digital art here), but their very presence, which, in turn, makes the characters’ minuscule sprites look miserable in comparison. It’s a good thing that such a large part of the game is spent sitting in the cockpit rather than walking around.

Sound

There is not much I can say about the MIDI soundtrack to the game other than it is quite functional. Just like the classic Space Quest theme (which, by the way, is constantly played around the StarCon corridors with whistling as the lead instrument, sounding cute at first but quickly getting on your nerves), most of the new compositions are given slightly futuristic arrangements yet are, in general, derived either from military marches (the Quirk / Goliath theme), from elevator muzak, or inobtrusive ambient themes. Created moods are well synchronized with the story — the background music in the Space Bar with its Latin rhythms is lazy and relaxing (this does create a comical dissonance when the Space Bar begins to be demolished by the freshly hydrated Space Monkeys), the music on the devastated colony world of Klorox II is tense and ominous at the intersection of two improperly synchronized à la Steve Reich keyboard loops, and the music at the abandoned space laboratory of Genetix mixes a little danger with a little melancholy, as if specially to let you know that you are going to encounter unpleasant evidence, but nothing specifically life-threatening at the moment.

Overall, the music is decent, the sound effects are top notch for 1992-93, and the obvious question is — where the hell is the voice acting? With Space Quest IV being one of Sierra’s first fully voiced games, and with the voice acting out there (particularly Gary Owens’ narration) as one of the game’s chief selling points, one could certainly have expected the sequel to make some progress in that department. In the end, though, it is all about the budget, and as late as 1992-93, voice acting for Sierra games was by no means a guaranteed proposal (see Larry V, Eco Quest II, Pepper’s Adventures In Time, and other examples as proof). In the case of Space Quest V, this is particularly unfortunate, given its propensity for dialog and wonderfully sharp-mouthed characters like Droole and Flo. There is so much dialog, in fact, that I am absolutely sure the game was designed and written with voice acting in mind — until reality stepped in and delivered its terms.

There are a few last-minute vocal effects, like the yowls of pain uttered by Roger each time he is punished for a stupid physical action, and the indiscernible mumble of the StarCon professor during test time (which kind of looks like an unintentional homage to Charlie Chaplin’s mockery of movie voices in Modern Times), but overall the lack of proper voiceovers easily puts Space Quest V as the first in line begging for a remake — which is not likely to happen, since in the past twenty years the fan community has mainly been busy recreating games from the studio’s older, parser-era period. Unfortunately, with Gary Owens having passed away in 2015, even if it ever comes to a fully voiced remake, perfection is no longer an option...

Interface

With the game developed at Dynamix rather than Sierra, it is hardly a big surprise that it has a somewhat different look from the typical Sierra game of the time. Although the basic principles of organizing game space and control interface remain the same, text windows and menus got a slightly more industrial, gray-metal sheen, and even the classic Sierra fonts were replaced by an all-caps version closer to the comic book standard (even dialog between characters occasionally came in the form of comic book speech bubbles). Since there was no voice acting anyway, this look might seem suitable for the game, even though it breaks continuity of the series (Space Quest VI would roll back these changes).

The main interface, nevertheless, retains all the standard elements of classic Sierra. The list of options to choose from includes the obligatory Look, Operate, and Talk icons, to which the game adds an experimental fourth: Order (replacing the far less practical, but somewhat more funny Nose and Mouth icons of the previous game). Unfortunately, the only time that the two have a useful distinction is in your cockpit, where «Talking» to your crewmates results in small talk on various subjects, while «Ordering» them to do something actually gets you moving around space and shooting stuff, if necessary. From a clean design perspective, I suppose this could have been handled more pragmatically, i.e. with an extra console on the cockpit screen; as it is, the «Order» option creates the illusion that you can boss around every single being in the universe, when in reality your commanding skills are strictly reserved to your crewmates.

As I have already mentioned, there is plenty of dialog to be had with said crewmates, but this does not translate to the rest of the game. The designers of Space Quest V did not have either the time or the budget of the creators of such concurrent games as King’s Quest VI and Larry VI, meaning that approximately 90% of «useless» point-and-click actions will get a strictly generic response. You will not be able to talk to trees or rocks, grope random stuff, or even humorously fail to pick up whatever cannot be picked up; at best, you can «Look» at all this stuff, but «Touching» it will be fruitless. (Sometimes it actually works in a detrimental fashion: there are a few instances in the game where you have to use one object on another so that their invisible hotspots intersect — otherwise, you get a generic you-can’t-do-that type of response and may be discouraged from trying out the correct approach).

The quasi-arcade sequences do not present much of a challenge, except for the infamous get-my-engineer-back-to-safety assignment where you have to guide your pod to Cliffy’s resting place and then use an extended mechanical arm to grab him. Even with the CPU speed problem taken care of (see above) this is still a bit messy and counterintuitive, continuing a long tradition of Sierra’s bumbled mechanical puzzles (Codename Iceman, anyone?), and it makes me happy that most of the «action» sequences in the game still take place in the regular point-and-click mode.

Verdict: Not a bad way for a Space Quest game to show some maturity... for once!

As I have already said, Space Quest V is rarely placed in the upper league of Sierra games, but there is also such a thing as a nice, solid, middle-of-the-road Sierra game: carefully designed, intelligently paced, with an interesting, if not outstanding plot and no particularly noticeable innovations to speak of. This is Space Quest V in a nutshell: nothing to be insanely proud of and (almost) nothing to be ashamed of, either. It made good use of all the technological advances accumulated to that point, it made its protagonist grow up a bit and show a few extra talents, and it seemed to give fans of the series an assurance that the adventures of Roger Wilco would continue evolving, retaining the series’ classic humor but also throwing in bits of action, romance, horror, or whatever other inspiration might come their way. It is quite a pity that this assurance would dissipate by the time of Space Quest VI — and then, of course, be gone for good.