Studio: Bethesda Softworks

Designer(s): Vijay Lakshman; Ted Peterson

Part of series: The Elder Scrolls

Release: March 25, 1994

St. George’s Games: Complete playthrough Parts 1-13 (13 hours 5 mins.)

Basic Overview

Just to impress everybody about how much not of an RPG-obsessed person I am, I should probably start this review with a stunning disclaimer that, as of the exact moment of its writing, The Elder Scrolls: Arena is the only game in the entire Elder Scrolls series that I have had the time to actually beat. I am familiar with all the other major titles in the series, all the way to Skyrim, but I still have a long road to travel here, and, as usual, I prefer to tackle that road in proper chronological order, which is a good way to let you look past the inevitable technological limitations of the old titles and assess them not from a «retro-historical» point of view, but from a «time machine» point of view, sort of reliving life from one stage back in time to another stage forward. When Arena was released, back in 1994, I had no chance whatsoever of playing it, for various reasons (one of them being that my PC probably couldn’t have handled the stress); but playing Arena before getting properly spoiled by the likes of Skyrim is precisely the way, I think, to be able to more properly appreciate both Arena and Skyrim, as well as everything that came in between.

Of the two big B’s in the world of CRPG, Bethesda and BioWare (there’s also Blizzard as the third one, but its primary focus is more on strategy and action than RPG), I am naturally more partial to BioWare, whose goals — at least, while the studio was in its prime — were always to combine an outstanding storyline, populated with memorable characters, with elements of role-playing; The Elder Scrolls have always prioritized role-playing over story, giving the player much more freedom of action at the expense of making these actions feel like they really, really matter. However, as far as tools for the «build-up-your-own-story» construction kit are concerned, few, if any, competitors have matched the ambitions of Bethesda over the years — and as The Elder Scrolls: Arena amply shows, these ambitions were there right from the very start. Pretty much every game in the series always tries to bite off far more than it can chew — and pretty much every one fails, to some degree or other — but the failures themselves still manage to be fascinating, and their sins forgivable.

Unlike BioWare, a company that pretty much started out with its dream transparently laid out on paper and went from nothing to stardom upon releasing its second game (Baldur’s Gate), Bethesda Softworks seem to have waddled into the RPG market almost by accident. For eight years since its incorporation in 1986 by Christopher Weaver, it was putting out a rather motley assortment of sports simulators, shooters, and rather lackluster action-adventure titles like the Terminator franchise; it is probably safe to say that few of those provide even purely historical interest at present time (I’ve not played any of them myself, but watching the old game footage on YouTube has not been particularly arousing). However, sometime around 1992–1993 the stars aligned rather happily for the company, putting together three talented people — designer / producer Vijay Lakshman, senior designer Ted Peterson, and programmer / engineer (also occasional composer) Julian LeFay. (Cue voice of doom) It has been foretold in The Elder Scrolls... that some day three heroes would cross paths in order to design a really cheesy game about teams of warriors traveling through an epic world, fighting each other in the various combat arenas scattered across the land until only the strongest remained, or some crap like that. Fortunately, collective intellect won over collective stupidity, and the raw game mechanism soon took on a life of its own, with its creators wisely following their instincts and creating something completely different from what was originally planned.

Thus, although The Elder Scrolls: Arena still happened to retain its original name, for whatever technical reasons forced it to, there are no «arenas» in the game whatsoever — instead, having (accidentally, I’d like to believe) discovered that all three of them were fans of tabletop RPGs as well as already prolific CRPGs of the Ultima variety, Ted, Vijay, and Julian simply decided to make nothing less than the hugest, grandest, most ambitious RPG of all time. Perhaps if they’d already had a lot of experience with the genre, they might have reined in their ambitions and settled upon something of a smaller scale — but fortunately for history, they knew very little, if anything, about how to make an RPG, which is a great starting condition for a terrible, laughable embarrassment if you lack talent and insight, or for something truly outstanding if you do not. And for all its major flaws and all of its under-reached goals, The Elder Scrolls: Arena was truly and verily outstanding.

Even those who would find the game tedious and unplayable today would still have to acknowledge that it was quite a breakthrough in several important aspects. It implemented the huge, near-infinite open world game mechanic like never before — absolutely breathtaking in pure geographic scope (even if most of that scope was rather illusive, as we shall find out eventually), it remains the great-great-grandfather of the majority of today’s open-world RPGs. It was, arguably, the first title to successfully and convincingly introduce first-person perspective into RPGs (inspired in large part by Ultima Underworld, for sure, but that game looks laughable next to Arena). It placed a huge emphasis on atmospheric properties, utilizing sound and visuals to trap the player in its virtual reality. It... well, let’s save all those other things it did for the actual review.

Unfortunately, it also did most of these things somewhat crudely — or, to put it more politely, it was somewhat ahead of its time with many of its ideas. In most of the veteran gamers’ memories, I believe, the legend of Arena has been largely eclipsed by the memory of The Elder Scrolls: Daggerfall, the follow-up title from 1996 which is commonly brought up as the proverbial Bethesda masterpiece from the early days. I happen to actually prefer Arena myself, and I think it is largely due to the fact that I’ve been late to the party by more than twenty years; today, Arena, as played through various DOS emulators on PC, no longer feels as cumbersome and unwieldy as it must have felt to most PC owners back in 1994, and to me, its sprawl feels a bit more balanced than that of Daggerfall. However, this is, of course, a matter of opinion — both games have their own elements of uniqueness, and ultimately it all depends on what you’re really here for.

Back in its day, of course, Arena had its fair moment of glory, with Computer Gaming World voting it the best RPG of 1994 and gamers worldwide amazed at its dashing sprawl. Yet due, among other things, to the fact that it failed to properly and definitively establish the lore of The Elder Scrolls — something that would only happen with Daggerfall two years later — Arena had the misfortune to become sort of the «spiritual black sheep» of the series, an early take that feels disconnected from the fantasy universe of Tamriel built up in the later titles. For that reason, present day devotees of the Elder Scrolls saga are often found scoffing at the game, inciting novices to start their journeys with Daggerfall (if they want a particularly harsh «old school» challenge) or any of the ensuing games from Morrowind to Skyrim. But I think that even if Arena happens to be totally excommunicated from the Church of The Elder Scrolls, it still has quite a few delights to offer on its own, as a stand-alone title. In fact, precisely because of the fact that it spends a little too much time looking over its shoulders at achievements of the past, always thinking about how to improve on them, rather than on building up a grand new universe for the future (which is the chief occupation of Daggerfall), it ends up being more adequate and balanced in some aspects than its somewhat chaotic follow-up hodge-podge of kaleidoscopic ideas. In the ensuing sections of the review I’ll try to show more specifically what I mean — and yes, we’ll have to resort to quite a bit of comparative analysis in the process.

Content evaluation

Plotline

Most of the Elder Scrolls games are, to some extent, defined by how their «main quest» is integrated (or not integrated) with the «side quests», and the specialty of Arena is in that, after a short while, it is only the «main quest» that remains worth following. After creating your character, you start the game in a dungeon where you, the last survivor of the loyal Imperial Guard, have been thrown by the evil mage Jagar Tharn after he has staged a coup against the Emperor Uriel Septim VII, imprisoning the poor guy in Oblivion and assuming his shape in order to rule for his own sinister purposes. As you escape from the dungeon, guided by the instructions of the friendly (but dead) sorceress Ria Silmane, your obligation is to restore the Emperor to power and deal with Tharn — to do this, a powerful magical artifact, split by Tharn into eight pieces, has to be found and reassembled piece by piece; only after this can you actually storm the Imperial Palace itself and confront the traitor face-to-face in a final showdown.

It is a simple and repetitive plot — perhaps the simplest ever in an Elder Scrolls game — yet, in a way, it is rather surprisingly effective. Starting with Daggerfall, you always run the risk of getting way too confused and mixed-up while sorting out the endless mutual strifes and bickerings of the various factions, with the big goals (if they can even be called big) getting diluted in an endless sea of local problems. Of course, this is all perfectly normal for ambitious CRPG settings, but sometimes there is something to be said about straightforward simplicity, too, and Arena is as simple as they come. Later games would be all twisted and zig-zaggy; Arena’s mechanism is straight as an arrow. Each of the eight parts of your precious artifact (the Staff of Chaos) is hidden in one of the eight provinces of Tamriel. By getting a first clue from Ria and then asking around, your hero is directed to a location in one of the cities, where some king, mage, or priest asks for an initial favor — which always means clearing out a huge dungeon — to provide a map of the location where the Staff piece is hidden, whereupon you go there and clear out a second huge dungeon to get to the piece in question. Then you get a dream vision of Jagar Tharn who gets more and more mad at you, even sending in a couple of assassins that are easily dispatched. Then rinse and repeat.

Ultimately, this means having to complete a whoppin’ sixteen huge dungeon crawls, two for each province, before the final, eighteenth one (the first one is your escape from the starting dungeon) where you shall have to confront your strongest enemies, including Tharn himself. Although there are some tiny bits of lore associated with each of these individually designed places (as opposed to procedurally generated mini-dungeons scattered en masse all over the continent), most of your time in them will be spent finding your way around and fighting monsters rather than talking or interacting in non-combat fashion. The good news is that most of these places have their own personalities — ruined castles, abandoned mines, ice-encrusted strongholds, mist-filled gardens, lava-choked volcanic craters — and although the designers’ fantasy eventually begins to run out toward the end, as a rule, scouting out each of these locations is its own experience, though it certainly has to do more with «atmosphere» than «plot».

The aforementioned tiny bits of lore are, however, relatively worthless. The basic thing for us to understand is that we simply have to go to the dungeon, kill everybody in our way, get the required McGuffin and go forward. Paying serious — let alone emotional — attention to your local ruler or wizard explaining why he or she needs the item in question is not in the least obligatory to complete your assignment. Very occasionally, you might require to collect bits of information in the dungeons you explore in order to answer some of the riddles that the game’s locked doors sometimes ask of you; other than that, there is hardly any «knowledge» you need to assemble in order to facilitate your progress or feed your emotions. A couple of the crawls are accompanied by your slowly unwrapping the details of some terrible Shakespearian tragedy that had happened in the place in question (such as the mini-story of the brothers Mogrus and Kanen inside the Labyrinthian), but there is no actual involvement on your side in these stories, and with minimal text and no voicing going on, their artistic value is non-existent: really, they’re only there to make the crawls a touch less monotonous.

Things are even worse with the side quests, most of which are randomly generated from pre-written blocks — these usually involve rescuing some damsel or noble’s son from a dungeon, accompanying somebody somewhere, capturing a criminal, or, on a rare occasion, hunting down a unique artifact that will help tremendously boost some of your stats. None of these quests, which you typically get from hanging around with innkeepers or nobles wherever you come to visit, have any relation to the «main quest» or, in fact, can even be considered as a minor part of the «plot»; they are simply there to provide extra content, extra opportunities to get extra loot and cash, buff up your character, and help you catch a breath in between the major dungeon crawls. I would typically find myself getting a small bunch of these early on in the game, then forget about them altogether — because you can really level up all the way you want while simply doing the main quest. (And those tiny four-level dungeons generated for side quests are usually very, very generic and boring anyway).

Still, in a sprawling RPG game like Arena there is something to be said about minimalism, I guess — and although the final encounter with Jagar Tharn is rather short and disappointing (he does not even get his own unique sprite, and by the time you meet him face-to-face, you’ll probably be leveled and buffed up to such a point that you’ll take him out in a jiffy), the way he keeps pestering and taunting you through each of your achievements does feel epic. At least there is a very clear goal and a very clear — and cleverly increasing in difficulty — path that leads to it in a very classic mythological, labour-of-Hercules sort of way. And while subsequent games would strive to make your living in Tamriel being a bit more on the mundane, realistic side, this is precisely what makes Arena stand out — a bit of an epic, poetic feel to it which would already in Daggerfall be replaced by a far more pragmatic and even cynical approach to all that hero business. It’s a bit like pitting The Iliad against A Song Of Ice And Fire, if you catch my drift here. There’s probably a place in our life for a little of both.

Action

Compared to how Arena looked and felt upon release, the things you could and would do within Arena must have seemed somewhat underwhelming. Essentially, Arena does what any generic RPG expects you to do. You start off with «rolling» a character (most people usually keep on re-rolling until the initial stats look impressive enough) — prior to which you may or may not wish to have the game assist you in choosing your class by testing you through a series of easy-to-see-through questions (e.g. "your neighbor stole your watch, do you (a) beat the shit out of him?, (b) hypnotize him to make him return it, (c) rob him blind in the middle of the night for revenge?"). Then you tweak your typical RPG stats (Strength, Intelligence, Agility, Luck, etc.) a little, and off you go to an existence that shall largely consist of three constituents: Communication, Commerce, and Combat. Beating the game is much more about grinding in all these three areas than anything else.

Simply put, to learn the locations of the artifacts you’re supposed to collect you have to travel around — usually at random — and ask the various people you meet on your journeys. They don’t have a lot to talk about — sometimes they can deliver you a random, and usually meaningless, piece of news for sheer virtual pleasure, or point you to a place where you can find a generic side quest to complete; but sometimes, completely at random, they do give out a valuable piece of information. Thus, all that’s needed here is patience. Once you have finally been pointed in the right direction, before invading one of the «macro-dungeons», you need to stock up on decent weapons and protective equipment (everything from armor to magic potions); this is done at local stores, all of which look alike, where you’ll probably do a lot of bartering at first, that is, before you become so overloaded with money that bargaining becomes merely a time-consuming chore. (I usually end up buying a shitload of health and other potions, which saves you quite a lot of time in the dungeons).

Finally, there are the dungeon crawls, which will probably occupy about 85-90% of your entire playing time — and it’s a good thing, because Arena is really all about dungeon-crawling. The smaller dungeons, procedurally generated for the sake of minor side quests, are not very interesting — they usually consist of about four levels each, with a small number of random enemies scattered around differently configured corridors and chambers, and once you’ve explored a couple of those, I don’t see how it could be particularly interesting or fun to waste time on even more. The large, hand-crafted dungeons, are an entirely different matter altogether — not only do they have interesting bits of unique design, but they typically offer an extra level of challenge, where you have to guess riddles to open locked doors, find your ways around deep pits and lava pools, locate hidden keys on bodies of occasional mini-bosses, and regularly meet new, stronger types of enemies as the older types grow weaker and weaker while you level up.

Combat itself, like in most classic, pre-action-adventure day RPGs, is not difficult, and its results usually have more to do with the current level of your character, as well as the luck of your dice rolls, than with true player agency. Incidentally, Arena was the first, or at least one of the first, games to introduce mouse-based combat into PC RPGs, but this just means that you have to constantly move your mouse back and forth while slashing at the enemy, requiring no special player agility at all; the results of your slashing will always be determined by your and your opponent’s respective levels — and quite a bit of luck, nothing else. Thus, (a) leveling up is really important, (b) packing stuff is really important, (c) understanding when to fight and when to run like crazy is really important. That’s about as much intelligence as it takes to beat Arena to its conclusion.

Now, of course, if you want to, you can get pretty creative, particularly if you are a magic user — like quite a few RPGs, Arena makes the mistake of being obviously rigged in favor of the wizard class. Thieves may be extra sneaky and fighters may be extra tough, but living your Arena life as a thief or a fighter ultimately becomes quite boring, whereas wizards have the advantage of constantly learning new, more complex and exciting (and expensive, not to mention mana-costly) spells — in fact, Arena boasts the presence of its own spell-constructing kit, where you can waste hours of your life designing the most bizarre spells in the world. Want to have a spell that launches a fireball at your opponent, while also poisoning him at the same time, making you invisible and sending you off to levitate in the air? Yes you can, provided you got the money and you got the spell points required for casting the little wonder. Easily the single most challenging and brain-wrecking task in the entire game is to come up with your own ultimate doomsday spell that shall make even the most dreadful boss creature disintegrate before your eyes in less than a second...

...the only problem here being that all these things are essentially not required, they’re all here for the sake of entertainment only. The regular spells that you can buy at the various Mages’ Guilds cover all of your needs perfectly just as they are, and the practical use of a complex spell that makes you invisible, cures you of poison, and destroys your enemy at the same time is pretty dubious in the first place — usually, you’d want to do those things separately rather than all together. It would actually be nice if, every once in a while, the game would force a magician to use the Spell Construction Kit — just to emphasize its importance for boss battles, for instance — but it never does. Consequently, having fooled around with the system for a short while, I quickly grew bored and disenchanted with it, sticking to regular spells from then on.

In the end, player qualities that Arena rewards the most are patience, obstinacy, and (optionally) calculation, which, of course, is hardly surprising for any CRPG veteran. Building up and properly equipping your character, accurately mapping out the huge, twisted dungeons, diligently saving all over the place after making another small bit of progression — all of these things demand far more of your time than they do of your intelligence. Hence the obvious question: with so simple a plot, and such trivial a path of action, is there truly anything in Arena that could be worth your time?

Atmosphere

Indeed, if there still remains one reason for people to continue bothering with Arena, it is simply the fact that it has a fairly unique «aura» to it. Perhaps the best way to feel it out is to compare the dungeons of Arena with what must have been its chief inspiration — Ultima Underworld, released two years earlier. While I have not played it myself, watching bits of gameplay on YouTube clearly shows just how much Bethesda specifically pilfered from its scrolling 3D landscapes. There is the same first-person perspective; the same endless labyrinth of stone corridors, walls and doors arranged in chaotic and befuddling manners; the same limited field of vision, with new walls and corridors — as well as unexpected enemies — rising to meet you out of the darkness, with creepy music following you around and occasional juicy pieces of loot strewn on the ground. However, the two years elapsed between 1992 and 1994 proved to be rather crucial: while Ultima Underworld’s dungeons, at best, might look «fun to navigate» to some people, Arena’s dungeons continue to feel creepy as hell, easily just as unnerving when you return to them in the 2020s as they were back in the era when they represented the ultimate pinnacle of digital technology.

Much of this has to do with the game’s handling of sound, arguably the game’s highest technical achievement and one of the finest examples of atmospheric audio in any game I have ever played, period (yes, it compares quite masterfully even to modern titles in that respect). But this is not the only component of the game’s atmosphere, far from it. On the whole, Arena succeeds in building up a bizarre, but believable alternate reality in which the principal, if not the only, goal is to survive, and in order to survive, you have to build yourself up as diligently as possible. Formally and superficially, this is a common goal in most RPGs, but not all of them flash it in your face as persistently as Arena does. Paradoxically, even if its sequel, Daggerfall, would on the whole be a much more difficult game, in which the balance between life and death is very much skewed in favor of death, Daggerfall, to me, rarely feels as tense and unnerving as Arena.

In their tales of their own struggles with Arena, people frequently complain about the difficulty curve and how it took them 15 or 50 tries to even get their character out of the starting dungeon. This complaint usually has more to do with not perfectly understanding how the game works — in addition to a lot depending on the luckiness of your initial rolls, you are pretty much supposed to take plenty of damage from even minor enemies, such as Rats or Goblins, at the beginning of the game, and use safe spots and niches to rest and recover. Once you got that simple tactic down, Arena is not particularly difficult, except when you run into one of its many bugs; however, even after that it does not cease to be creepy.

Honestly, there are fairly few games out there in which the enemies would be as persistently nasty as they are in the Arena. Typically, they creep up on you from somewhere ahead in the darkness, where you can sometimes discern them from a little afar by the distinctive sounds they make; however, they are just as liable to creep up on you from behind and stab you in the back when you least expect it (usually, I think, it happens when you go past a closed door without bothering to check what is behind it, and alert your presence to the enemy — but sometimes it feels as if the game is simply scripted to have fiends materialize from nowhere). As a rule, they are really ugly and really persistent, their only purpose in life being to hunt you down for no reason at all — malicious killing machines, yet endowed with their own species-specific personalities. However, as you gradually level up, formerly formidable enemies gradually become nuisances that you easily dispatch with a couple blows or a couple well-placed spells — until, by the end of the game, once you have accumulated enough XP, even the most dangerous challenges such as Liches or Vampires go down before you like sacks of potatoes.

At the beginning of the game, though, hoo boy, you’re in for some really tough time. At least the opening dungeon is relatively small; but already your very first serious mission — find a tiny piece of parchment in the huge dilapidated castle of Stonekeep — can overwhelm you with its sheer scope and deadliness. The designers lure you in with simple enemies at first (the same rats and goblins that you have already become accustomed to in the starting dungeon), then begin mockingly introducing you to speedy wolves, brutal orcs, nearly unbreakable skeletons, paralysis-inducing spiders, and, finally, club-wielding, disease-spouting Ghouls, defeating even one of which takes pretty much all you’ve got... and there’s a whole pack guarding that blasted parchment. Above all, it is the space of the whole thing that shall take the wind out of your sails. Dining halls, libraries, flooded dungeons, earthy basements, underground currents — by the time you’re finished with your dungeon crawl, you’ll be literally sweating. And there is no «Recall» spell as there would be in Daggerfall — having made your way deep into the bowels of the dungeon, you’ll have to crawl out of it as well, only praying on your way back that all those innumerable enemies have not yet had time to respawn.

As you gradually level up and become more used to your enemies’ treacherous tactics, the atmospheric qualities of Arena are liable to begin inducing boredom — even if, as I already said, the designers try to keep the main quest dungeons as diverse as possible, there is only so much you can do with a fixed set of starting blocks, and by the third or fourth piece of the Staff, all those underground pits and lava rivers will no longer feel particularly exciting. Still, there always remains a certain element of charm in the meticulous exploration of all that hand-crafted dungeon space, especially if you are endowed with the famous Passwall spell that allows you to remove a piece of the dungeon wall if it seriously gets in your way or if you’re too tired of endless backtracking from dead ends. Eventually, subtly, the game morphs from «survival horror» to «cartographic lessons», which could very well appeal to the obsessive elements of our nature — my main complaint is that the cleared maps, which all look so nice and neat on the Map screen, are wiped clean after you leave the dungeon; so if you want to return to one of them for some reason, you’ll just have to start mapping them out all over again.

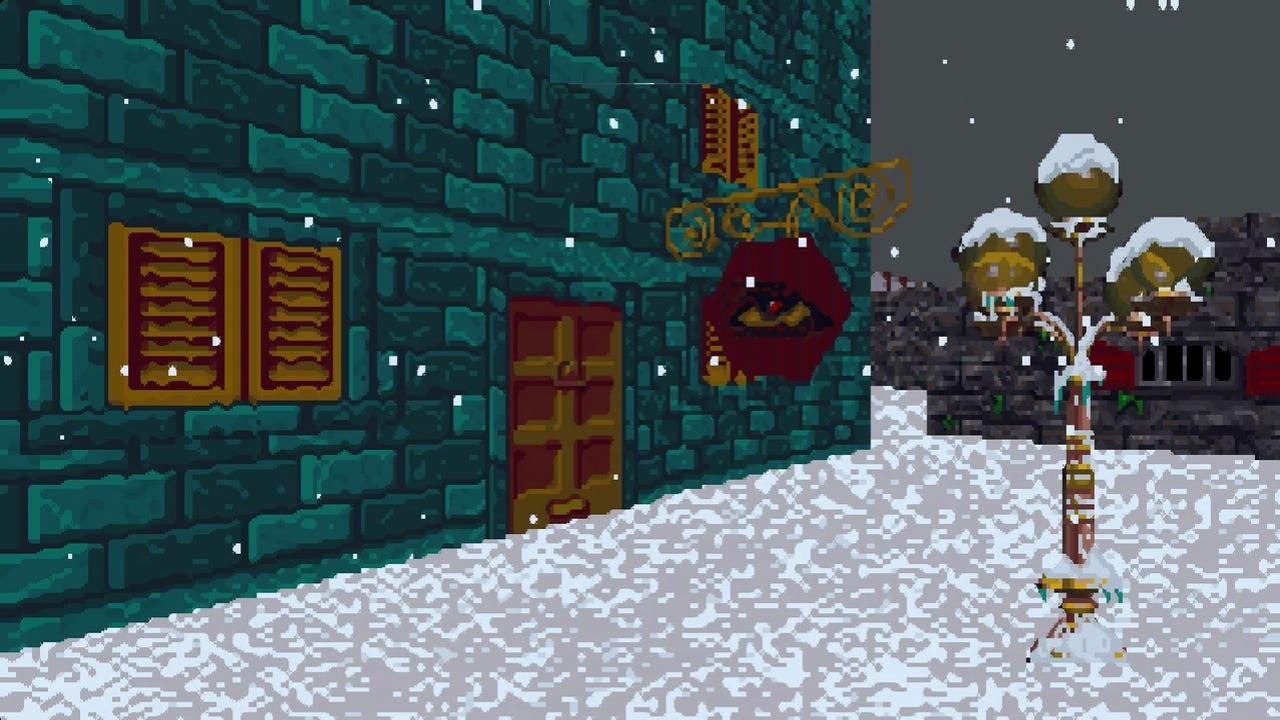

Outside of the dungeons, the atmosphere is, of course, provided by the vast open spaces — endless plains strewn with randomly generated roads, trees, rocks, farmlands, and an occasional loot-filled, monster-populated mini-dungeon every once in a while. Added to this is an expertly crafted day-and-night cycle and occasional weather effects (e.g. snowfalls in the Northern provinces). Unfortunately, as it usually gets with procedural generation, the vast world does not really come alive all that much: there is nothing you can do with the immovable random decorations, and you cannot even properly get by foot from one area to another. Interaction with the locals scurrying around the towns and the countryside is possible and at first even looks varied as they introduce themselves to you, share pieces of local or general news, drop hints about finding work and provide information on the city’s taverns, guilds, and shops; pretty soon it becomes obvious, though, that all of that chatter is procedurally generated just as well, and that not a single person you meet in the streets or inside the building is actually a personality — not even the several «specially» named characters (like «Queen Blubamka of Rihad»!) who have unique pieces of main quest-related dialog (once they’ve exhausted those couple of paragraphs, they simply revert to being a part of the same nameless crowd).

Generally speaking, it is clear that the creators of Arena were first and foremost obsessed with size. The big cities of Tamriel are truly big, each one containing dozens of landmarks; the dungeons generated for the main quests take hours and hours to properly map out; the distances between cities are infinite; and if, through some crazy desire to set a really stupid Guinness record, you wanted to visit, explore, and map out each city, town, village, and dungeon on the continent, it could literally take you a lifetime of doing nothing else (although Daggerfall, I believe, would take that approach even further). For PCs back in 1994, the results must have felt monumental, provided they were capable of running the game in the first place; today, eyeballing this largely meaningless vastness is about as exciting as settling down in your comfy chair and reading aloud the first half a million sequences in a decoded strand of DNA. Yes, we know that space is infinite but we also know that it is mostly empty — although, granted, some people may get off on the idea of vast empty space.

To me, the most appealing point of Arena’s atmosphere is not the game’s sheer size, but the very contrast between «safe» and «dangerous» space. The best feeling? When you happen to arrive in some town late at night, with all the shops and guilds closed and occasional monsters and bandits roaming the streets. You’re looking for a place to stay, and there is nobody around to give you directions, and suddenly some unknown enemy hits you in the back and takes off a solid chunk of your health bar, and you have no idea if it’s a measly Orc or an overpowered Wraith... and you run for your life, desperately looking for signs of salvation, and then, finally, you see a heart-warming tavern sign... you rush inside, still pursued by your unknown enemy, and suddenly find yourself in the «comfort zone» — bright, warm, pleasant, with merry music playing around, an opportunity to rest your bones, recover your health, and check the local gossip. That is the kind of thing Arena does incredibly well, and even if it cannot properly bother to make any of its NPCs come alive, at its best, it makes you feel very much alive by staying on your toes in a world where pretty much everything out there is out to get you, sooner or later.

Strange as it seems, too much emphasis on the plot might have probably ruined some of the game’s atmosphere, as it ended up happening with Daggerfall, a game which — I absolutely insist — is seriously less atmospheric than its predecessor, much more concerned with giving the player more freedom of action and pseudo-diversity at the expense of emotional reactions. I, therefore, do not mind all that much that we do not get to properly bury ourselves in the court intrigues of the many rulers of Tamriel, concentrating instead on killing as many monsters as possible to get to that coveted next rank.

Technical features

Graphics

While it is obvious that in retrospect, the visuals of Arena have no chance of remaining its strongest selling point, back in 1994 Bethesda’s achievements on this front must have felt quite spectacular. With a native VGA resolution of 320x200, the game’s engineers still managed to get it at least up to the level of Doom — no mean feat for the time — and perhaps even improve on that level, as the graphics of Arena strive for a bit more realism and complexity. However, they also have to struggle with the same issues as Doom, or just about any 3D action or RPG game released at the time — most notably the «open world» principle, under which the number of on-screen visuals available for the player is technically supposed to be infinite, meaning that they are all composed of pre-crafted «building blocks» that may be combined in an endless variety of ways. As a rule, this principle does not really transform into aesthetic beauty; the only thing that matters is the illusion of plunging the players into an alternate reality, unconfined by the limits of their monitors.

However, I would not be too sure to insist that the graphics of Arena are entirely subdued to purely pragmatic purposes, as becomes obvious when you compare it to the likes of Ultima Underworld. First, adequate care has been taken of the little details. The sprawling dungeons feature wall decorations, rusty chains, dirty weeds, gnawed bones scattered across the floors, etc. The cities, towns, and hamlets of Arena have lamp-posts, fountains, statues, nicely trimmed lawns, etc. Probably the most disappointing places are interiors within townhouses — as a rule, they just feature empty spaces, sometimes with tables and chairs (there aren’t even any closets or beds, for that matter — whenever you go to sleep in an inn, one wonders whether you’ve just had to spend the entire night flattening your bones out against what looks like a primitive surgical table) — but at least you’re not really supposed to be spending a lot of time in there.

Second, it would not be right to deny a certain style to all these building blocks. The dungeons, with their huge stone slabs, earthen floors, and low-hanging ceilings, have a brutal, claustrophobic look that sometimes actually makes you wonder about who and under which circumstances could ever have populated their territory with such menacing structures. The towns, most of which look very much alike apart from a few environmental details here and there (e.g. palm trees in some regions vs. fir trees in others, etc.), give off the probably intentional-and-desired effect of «human anthills», where people scurry about their business just because such is the law of nature. In some ways, the relative primitiveness of the graphics even in comparison to Daggerfall only accentuates the idea of the world being a dangerous and depressing place (both the exteriors and the interiors in a typical Daggerfall town would look a tad nicer and cozier, suppressing the overall feel of danger).

Third, the 3D aspects of Tamriel are handled reasonably well. Although the game’s draw distance is laughable by modern standards (you can do something about it by fooling around with the Details slider in the settings, but not too much), having blurry faraway objects suddenly transform into houses, statues, and people before your eyes is still impressive — or jump-scary, whenever your advancing in a dungeon triggers the emergence of some particularly nasty enemy from out of the shadows (one reason I always go for a Light spell early on in the game — somehow having your Vampires and Golems appear out of a brightly lit nothing slightly reduces the chances of a heart attack if you have them appear out of total darkness right under your nose). And the scaling issues with NPC and enemy sprites are almost non-existent: they look just as realistic up close as they do from several meters away (compare, for instance, the really clumsy scaling results with Sierra On-Line games released just a year or so earlier, when small-size sprites would look awfully pixelated when moved to a virtually «close-to-the-player» position). (Of course, we’re talking 1994 standards here, not 2020.)

Serious care was applied to the enemy sprites, making most of the monsters truly antipathetic. The multi-legged hissy spiders are all brown legs and feelers, ugly as roaches and stretched out like Martian war machines (more intimidating than spiders in Daggerfall, which kinda look like puffed-up rubber toy models in comparison). The vomit-colored ghouls look like walking puddles of infectious disease (which they are). The ghosts and wraiths actually look ghostly, with semi-transparent pixelated bodies through which you can walk (if you are brave and sturdy enough, that is). The Liches have rather uncharacteristic manes of red hair flowing atop their skulls, which gives them a bit of a progressive rock-star look on the whole — an original touch that actually makes this type of enemy more memorable than the one in Daggerfall. Unfortunately, this does not apply to the main antagonist (Jagar Tharn), who, for some reason — perhaps they ran out of budget at the last minute — does not even get a unique sprite to his name and is «disguised» as just a regular Vampire, which always confuses players at the end of the game (and makes the final boss confrontation quite underwhelming).

On the other hand, Jagar Tharn is one of the few game characters who gets an actual close-up (along with Ria Silmane and the Emperor), so that’s at least worth something — and speaking of close-ups, the game’s few attempts at actual hand-drawn art, mostly represented by exterior depictions of the eight locations containing the eight pieces of the Staff, are surprisingly vivid rather than purely schematic. Too bad they couldn’t have more of them, to make at least some of the game’s locations a bit more individualistic.

Sound

If there is one thing that Arena does better than most of the early games in the Elder Scrolls series, it is the audio part of the entertainment — I’d go as far as to say that the game is more worth picking up to be heard than to be seen, and that most of its atmosphere is conveyed by means of (a) its actual musical soundtrack and (b) one of the most effective uses of sound effects in a video game I’ve ever witnessed. The full CD-ROM edition of the game also has a third audio component — voice acting — but it’s a really small one, even if it does significantly contribute to the atmosphere as well.

Let’s start with the soundtrack. It was composed by relatively little known video game composer Eric Heberling, who had already provided the General MIDI soundtrack to Bethesda’s proto-Doom-like Terminator: Rampage — which is certainly OK as far as shooter-style rhythmic electronic soundtracks are concerned, but predictably monotonous in its harsh, kill-’em-all aggressive vibe. By contrast, even if the collective length of all the tracks written for Arena barely exceeds 40 minutes, they feature an astonishing range of vibes and attitudes — and some are even quite catchy at that! Considering that, as you stroll through Tamriel’s towns and dungeons, this soundtrack has to accompany you for hours on end, it is almost a miracle that I never find myself wishing to turn down the music, despite its continuous loops.

Heberling introduces a fairly strict division between «safe space» and «dangerous place» music — the tracks played at daytime in the towns and countryside, on one hand, or at nighttime and inside the dungeons, on the other. For the first group, the main inspiration probably comes from various strands of Renaissance music, though he obviously applies the «ABBA filter» (take a classical piece and simplify it to the point of being instantly memorable and accessible, that is) and makes full use of MIDI synths as autonomous atmospheric entities rather than just piss-poor emulations of real instruments. The result is some truly beautiful soundscapes such as ‘The First Seed’ (which typically plays on bright summer days inside and outside the cities) and ‘Winter In Hammerfell’ (playing, respectively, on wintery, snowfall days in the same locations). There’s really nothing like getting enveloped in the «cute solemnity» of the former or the «friendly frostiness» of the latter when you need an antidote to the robotic randomness of Arena’s hustle-bustle going around — with the slightly otherworldly feel of the MIDI tones (and I’m pretty sure it just wouldn’t work if played on real instruments), the game is instantly elevated to a whole other level, making it so much easier to suspend disbelief than through chatting with the lifeless, AI-generated townspeople.

The «dangerous» music is more on the ambient level; thankfully, it never goes into full-on shooter-mode (after all, you are not supposed to rush through dungeons in Arena, shooting up baddies with badass-looking carbines — it’s a slow and meticulous affair here), preferring instead to concentrate on suspenseful, unnerving tones; one possible complaint might be that there is no actual «combat music» even when you actually run into an enemy, but since you run into enemies so frequently, that might mean too many abrupt interruptions, so the decision to keep the same low-key suspenseful ambience even when you start hacking away at a pack of goblins is understood. In any case, the experience of sitting through a couple hours of this creepy ambience and then finally escaping the dungeon for the local tavern, where you are greeted by a cheerful bit of Celtic dance, is an absolutely heartwarming one.

As monumental as later era Elder Scrolls soundtracks would become, naturally culminating with Skyrim, there is an absolutely unique charm to Heberling’s creation here — and I am not saying this out of general nostalgia (which I couldn’t experience even if I wanted to, having never played Arena until the 2010s) or out of some «early MIDI music is always cool!» puffed-up principle: I just happen to recognize talent when I hear it, and I think that Heberling actually made the world of Tamriel a more unique place in nature than Jeremy Soule did with all the Elder Scrolls games later on (starting with Morrowind). The Arena soundtrack is simpler, quieter, less pretentious, a little child-like in places, and does a much better job of transporting you into a universe of «naïve childish beauty (and/or terror)» than the later soundtracks for games that were trying to advance from the level of pure make-believe to a certain degree of «fantasy realism» (and, for that matter, failed more often than succeeded in achieving that goal anyway).

Another area in which the game truly excels are the sound effects — although this applies exclusively to its dungeon-crawl sections. Inside the dungeons of Arena, hearing is even more important than seeing at times: enemies typically announce their presence to you by making typical sounds which you can hear from afar, coming from ahead in the corridors or even from behind the walls (so sometimes it takes a long, long time for you to face an enemy after having been made aware of its presence). And the effects work really well — particularly at the early stages of the game, when you have to be constantly on the watchout for overpowered enemies who can dispatch you very quickly if you get ambushed. Somehow, those couple of seconds allocated for each type of enemy characterize them perfectly in individual ways — from the busily angry mumble-grumble of the Goblins to the sheer carnivorous guttural roar of the Orcs; from the ethereal wails of the Ghosts that somehow manage to combine sadness, surprise, and menace at the same time to the «advanced» level of the same combo from the Wraiths (who add a particularly threatening guttural croak to the «cleaner» Ghost tone); from the cat-like venomous hissing of the Spiders to the «never-a-moment-of-peace-for-poor-me» constipated moans of the Ghouls; from the calm, cool, and collected pitch-black-deep roar of the fire-breathing Hell Hounds to the terrifying battle scream of the Vampire — I’d really like to give out a hug to whoever designed (and voiced!) those effects. Not only are they cool per se, they are also, to a certain degree, unpredictable, and not always corresponding to the usual stereotypes we associate with these kinds of enemies.

Finally, the full CD-ROM edition of the game throws in a bit of voice acting — specifically, a female voice for the visions you get from Ria Silmane (allegedly provided by one of the female programmers at Bethesda) and an unknown male one for Jagar Tharn (who also only appears in visions). Tharn’s actor overstates his function a bit with way too much mwahaha, look at me I’m so evil! pizzazz, and Silmane’s voice is rather monotonous and emotionless, but neither performance is cringeworthy, and I find it almost surprising how much they actually contribute to the atmosphere — even with their relatively rare appearances, they provide a bit of extra urgency and thrill that is very much needed to alleviate the robotic mechanicity of the miriads of identity-less NPCs in the game. (Why they never bothered to add any voice acting to Daggerfall beyond the opening scene is a mystery to me — surely this would have been even easier to do in 1996 than in 1994).

I am sure that a lot of Arena’s audio charm has to do with the slightly «amateurish» nature of the game — with the Bethesda team plunging into the genre without any previous experience, and with PC-MIDI technology still relatively fresh, they were not nearly as dependent on fantasy game clichés as just about everybody has been for the past twenty years or so. What other players might, therefore, dismiss as a naïve early approximation to how a fantasy RPG might sound, I prefer to approach as an inventive and occasionally unconventional take — giving the game its own unrepeatable flavor. Ironically, much, if not most of this soundtrack would later be carried over to Daggerfall as well, but while the older tracks would be augmented by a whole bunch of new soundscapes, none of them would quite match the weird magical effect of the Arena compositions — almost as if Mother Nature wanted to show us how «inspiration» eventually settles into «routine» (although I still prefer most of what Heberling, with his more «playful» approach, did for the series to Soule’s «monumentality» that started with Morrowind and continues on to this very day).

Interface

In terms of general gameplay, Arena did not revolutionize the traditional RPG mechanics in any obvious way I could think of. From the start, your character has the same standard set of parameters that most RPG experiences have, some of which are more important for one group of classes (Strength, Vitality, etc. for a Fighter-type class) and some for others (Intelligence for a Mage-type class, etc.), and all of which are influenced by the relative luck of your initial rolls (during character creation) and subsequent ones (when you level up). XP for leveling up is harvested in a very simple way — by killing monsters and absolutely nothing else — but the good news is that in order to beat the main quest in Arena, you don’t necessarily have to grind: as long as you do not arm yourself with a walkthrough and make a straight beeline for your coveted target in any of the main dungeons, instead of exploring them meticulously and mopping up all the monsters, you are guaranteed to level up rather smoothly. People often complain about the opening dungeon being too hard, but I never experienced the same kind of problems with it as I did with Daggerfall (where it is indeed recommended to quickly find the shortest way out of the dungeon as soon as possible).

The main interface, with a grid of options at the bottom of the screen, is convenient enough to be operated either with the mouse or with some nifty keyboard shortcuts. If you want to cast a spell, for instance, you click on one of the options to open up a menu of available spells in the bottom right corner of the grid, leisurely choose the spell (since opening the menu pauses the game) and blast the enemy; later on, you can press a shortcut key to re-cast the spell rather than reopen the menu again (this is my preferred way of healing myself — if you have enough mana, patching yourself up right in the middle of combat with even your toughest enemies can be a cinch). If you want to save mana and use up a charge on one of your magic objects (some of which you can also loot in dungeons, while others can be bought for astronomical sums at blacksmith shops — I am personally much more of a seller than a buyer in this game), you open up a similar list of artifacts in the same window, although, to the best of my knowledge, this is an action for which there is no keyboard shortcut.

Moving around is performed with the aid of a map (which opens up in a separate window) and a compass; the map is fairly simple compared to the 3D vision-breaking monstrosities of Daggerfall, and you can even make nifty little notes, for instance, to mark the locations of valuable loot if you are already overloaded and want to come back later. If you want to travel from one town to another, you open up a separate «maxi-map» of the provinces of Tamriel where you circulate between locations. Travel itself is fairly uncomplicated — it merely eats up your time — and the only drawback is that there is never a set time for your arrival anywhere, so you may very well end up at your destination in the dead of night (and be immediately attacked by a bunch of bandits or ghosts).

Dungeon-crawling is generally not too complicated, and the «good» news is that there is practically no way to die in any dungeon other than be killed by enemies — you cannot starve, you cannot hurt yourself by falling into a deep pit, and you cannot drown in any underground water current (unless you happen to be paralyzed by a spider while in the water, in which case you instantly drown — one reason why my preferred character race in Arena is always High Elf, as these guys are naturally immune to paralysis). Oh, right, you can drown in a river — if it happens to be a Lava Current, that is, and you have no spells or potions that could make you resistant to fire. One reason, however, why I tend to avoid swimming if at all possible is that this happens to be one of the most bugged areas of the game: much of the swimming takes place under the stone floors of the dungeons (not sure how this is possible physically, but that’s 3D game magic for you), and if you happen to emerge in a place guarded by an overhead enemy, you tend to get stuck, unable to do anything while the ruthless fiend pulverizes your health bar from above. (The same can also happen when you fall down a pit and navigate the underground passages in one of the game’s «mine-type» dungeons, so beware!).

Speaking of bugs, the original game was quite heavily criticized for their variety and game-breaking potential — something that would later go on to become more or less a staple for the Elder Scrolls series in general, but can, perhaps, be excused as an almost inevitable consequence of an unhappy marriage between Bethesda’s limited resources and limitless ambitions. In any case, playing the game decades later on DOSBox, where just a bit of twiddling with the settings gets the game to run quite smoothly on PC, was more or less a walk in the park for me. Yes, the combat thing is very primitive — all you have to do is wave your mouse around the enemy, mash the attack button and pray your hit connects — but then, precisely how much more primitive is this than the shooting mechanics of Doom, or just about any random shoot-’em-up / beat-’em-up game in which the quantity of mowed-down enemies matters more than the quality of the actual fight?

Essentially, most of the complaints about the playing mechanics of the game are exactly the same as applied to any other RPG. For instance, the loot system: for your first couple of dungeons, you shall probably be excited at every single stash of loot you find around the place, but pretty soon you’ll get overloaded with tons of useless crap, all of it likely inferior to the weapons and armor you are already equipped with, and will either have to drop it or waste time hauling it over to various shops to bargain with the merchants (actually, there is only one type of merchant in Arena, always conveniently doubling as a blacksmith). Eventually, you’ll have way more money than you really need for anything, at which point collecting loot will simply be an optional bore. Another thing is the already mentioned «Spell Construction Kit» — an idea that sounds good in theory, but is absolutely useless in practice, since you can easily achieve any goal in the game by simply using whatever is pre-available at your local Mages’ Guild. But in fact, complaining about these things is not too honest, either — they are completely optional, as, for that matter, is almost everything else in the game that is not directly related to the goals of the main quest.

Verdict: A simultaneously humble and ambitious start to the Elder Scrolls saga — one in which atmosphere matters more than historical importance.

You may have noticed that throughout this review, I’ve been surreptitiously throwing out little jabs at Daggerfall, the second game in the series — but not so much to undermine the legend of this fan favorite as to point out that, contrary to popular opinion, upon release Daggerfall did not, in fact, make Arena fully and completely obsolete and redundant. In trying to do more, more, more, more than Arena, the same way that all the games in the GTA series would try to insanely expand the amount of choice available to players of Grand Theft Auto III, Daggerfall ended up losing some of the first game’s atmospheric charm and «primitivism». I actually like, for instance, how the Main Quest of Arena is structured like a compact piece of some traditional Greek or Indian mythological epic, where Daggerfall, on the other hand, would plunge straight into all sorts of quasi-medieval political intrigue where you would soon lose the multiple threads of whatever was going on. I am more or less satisfied with the limited number of side quests that can you pick up — as uniform and monotonous as they are, they feel a bit more honest than Daggerfall’s simulation of an incredible diversity of tasks which, nevertheless, still amount to the exact same thing (visit a dungeon, mop up all the occupants, find something / someone and bring it / him / her back). And that sonic atmosphere of Arena... say what you will, but there is still nothing like it in subsequent games.

There is a funny paradox embedded inside Arena: while — purely formally — being the biggest game in the entire saga, the only one in which you can explore the entire continent of Tamriel and map out its contents for literally years and years, it is also the smallest in terms of actual original content. Outside of the sixteen dungeons of the Main Quest, there is little to do in Tamriel other than simply walk around Tamriel, be a ramblin’ man, trying to make a livin’ and doin’ the best you can. Some will rightfully say that this is a somewhat cheap attempt to deceive the player, lure you in with promises of a huge sprawl, all of which turns out to be generic, repeatable routine (hey, sounds just like real life for most of us, doesn’t it?). But as long as you are properly forewarned — disregard the hype, only believe 100% verified information! — there’s a certain kind of charm, too, in this «simplicity-over-complexity» approach, where you can feel yourself being a tiny grain of sand in a huge, infinite world while at the same time realizing your own epic importance in a save-the-world-from-tyranny kind of mega-quest.

It’s funny to realize that with all the technical and substantial progress in the art of video gaming, the one thing that modern RPGs are no longer capable of replicating by definition is that exact feel — simply because it would take too many resources and too much work for a procedural generation of an Arena-type world on the modern level of gaming demands. This is neither a good nor a bad thing; it only means, as I never cease to repeat while writing either about music or about video games, that certain types of sensual experiences are exclusively confined to their respective eras (in this case — a particular, very short, time window in the mid-1990s), and that losing the opportunity to wind up a game like Arena on one’s computer would mean losing access to a pretty unique type of sensual experience indeed. Fortunately, with Bethesda having released Arena as freeware quite a long time ago, there is little danger of that as long as there is at least a single «Eternal Champion» running around with a DOSBox emulator.

[Technical note: You can clearly see how much more popular Daggerfall remains in the hearts of gamers through the sheer fact that there is a complete and fully working modern version of Daggerfall, written by loyalfans in the Unity engine, openly available to the public — however, the parallel OpenTESArena project, having started around 2016, still remains in its initial stages and does not even have a fully playable demo. Honestly, I do not hold much hope, but I can at least dream that some day freedom fighters around the world might be able to resume their hunt for the Staff of Chaos in a smooth, perfectly running and bug-free modern graphic environment.]

This and other video game reviews at St. George’s Games

I think these old midi soundtracks generally do a good job of matching medieval sounds with catchy melodies. I was quite partial, to the extent of having tried recreating it in music notation, to the medieval piece from the Lost Vikings 2 ost (called Dark Ages) which I think is also from around 1994. These pieces that you linked actually seem better than that LV one. I always wonder where these video game composers come from, they're typically totally unknown to me. Are they amateurs with an interest in midi music or just people who studied composition at a music school?

I think you didn't comment on the idiotic cover image of the porn model next to the three barbarians. Given that it's the first thing you might see when you get the game it's a pity they elected something that would immediately date the game to not just a period of different technical capabilities, but one of seemingly different values.