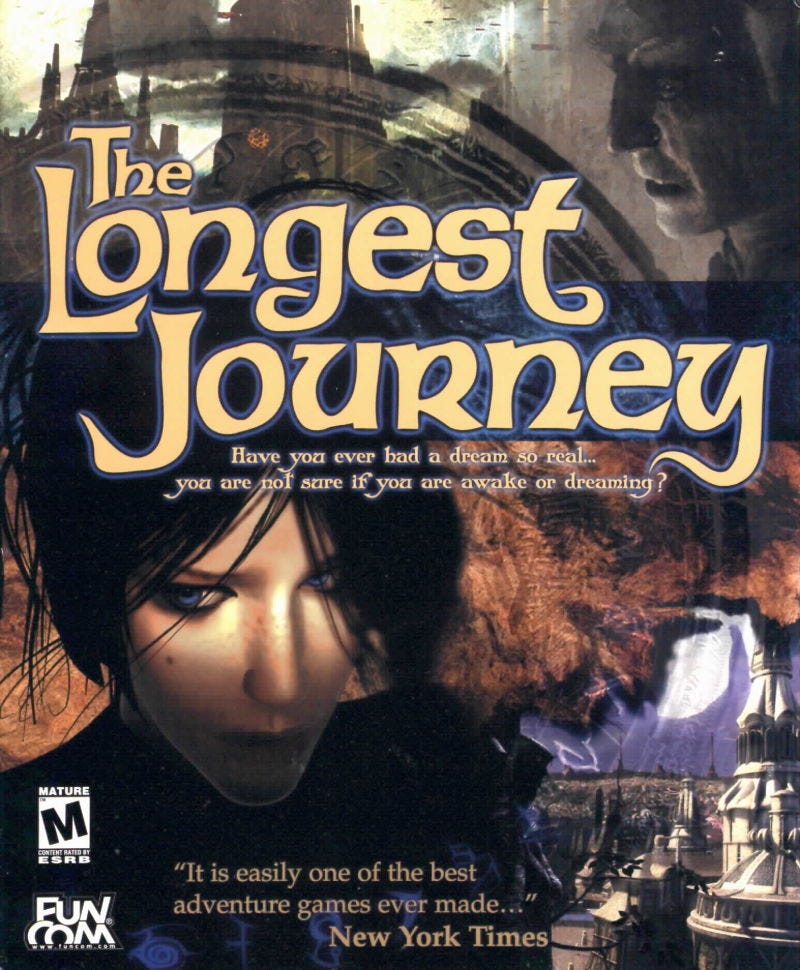

Game review: The Longest Journey (1999) - Part 1

Studio: Funcom

Designer(s): Ragnar Tørnquist

Part of series: The Longest Journey

Release: November 18, 1999

St. George’s Games: Complete playthrough, parts 1-17 (17 hours 20 mins.)

[Note: Starting this week, most game reviews (except those for very short, old titles) will typically be published over a biweekly period - the first part will contain the “Basic Overview” and “Content Evaluation”, the second part will have “Technical Features” and “Verdict”.]

Basic Overview

Conventional historical narrative (such as ensconced in Wikipedia, among other sources) tells us that, although adventure games were essentially dead in the US by the turn of the millennium, they continued to persevere on the European market — which was originally quite slow to catch up with the express trains of Sierra On-Line, LucasArts, and Cyan, but turned out gallant enough to pick up the fallen banner once American gamers had decided that expeditely shooting stuff up was, after all, much preferable to slowly solving stupid puzzles.

While this is not completely true (no generalization ever is), a brief look at a representative list of adventure games does indeed confirm that sometime around the late 1990s / early 2000s the balance switches in favor of such European studios as Cryo Interactive (France), Microids (also France), House of Tales (Germany), Detalion (Poland), Future Games (Czech), and others; most of these were relatively small-scale studios with limited budgets and, consequently, small backlogs (Sierra’s list of titles dwarfs each and every one of them), but in between them all, they at least somehow managed to keep adventure game design on the list of paid jobs (as opposed to completely falling into the hands of computer-savvy devotees working D.I.Y. style on their off days, of which there was also a lot in the early 21st century). The problem, unfortunately, was that in order to prove the ongoing vitality of the genre, you did not just need a studio willing to pay for the job — you needed people with vision, the European equivalents of legends like Roberta Williams and Al Lowe and Ron Gilbert and Tim Schaefer and Jane Jensen or, heck, at least the Miller brothers; people who would not merely pay tribute to the big successes of the previous decades, but actually advance them in a variety of ways.

The main reason why relatively few of the games produced by these studios achieved great fame on the international market was not the international market’s willing ignorance of adventure game titles as such, but precisely the fact that, while many of them were nice and all, they did not exactly demolish the stereotype of an adventure game as something that belongs squarely in the past. Even a genuinely visionary game like Benoît Sokal’s Syberia could still be critically lambasted on so many points that defending it on some sort of «objective» level would be nigh impossible. To keep the genre alive, the European market needed to produce at least one game that would unquestionably, irrefutably make all or most of the Top 10 Adventure Game lists of all time for years to come. That game happened to be Ragnar Tørnquist’s The Longest Journey — and it totally and absolutely deserved it.

Tørnquist, a handsomely dashing (if I do say so myself) Norwegian graduate of Oxford’s St Clare’s School, was hardly what one would call a technician — in his college days, he mostly studied philosophy, history, and art, and eventually got sufficiently savvy in drawing and animation to be hired at Norway’s studio Funcom as a writer and designer. From 1993 to 1999, Funcom was mainly known for small-scale action and sports games, some of them licensed from Disney and other film studios — nothing particularly special or critically acclaimed. However, once its new designer gradually rose high enough in the ranks, he pitched a creative idea which would probably have been vetoed by any American videogame studio at the time. Funcom, whose managers might not yet have learned to calculate their budgets that properly, had the good sense to support it — and ended up with such a critical and commercial winner on their hands that it allowed them... to go into the MMORPG market and produce titles like Age Of Conan and The Secret World. Okay then.

What exactly was the secret of The Longest Journey? It was certainly not a game immune to criticism, as we shall see below in extra detail — from the more than questionable graphics to the often ridiculously difficult not-that-crap-again puzzles, one could (and did) accuse it of the exact same sins which, in many people’s eyes, had doomed the original adventure game market. Its universe and storyline, though certainly original and even unique in some ways (we shall get to this soon), would hardly be enough to make people forgive the game’s transgressions. I read many a thumbs-down review of The Longest Journey from people who just «didn’t get it» — mostly because they focused their attention too much on infamous travesties such as the Rubber Duck Puzzle (see below), and stopped right before making that small, but necessary leap of imagination which would have brought them to the exact place where they needed to be. But change the angle just a bit — make a quick duck sideways to avoid staring into the large hat of the lady in the seat in front of you — and all will be different.

It is not coincidental that one of the chief inspirations for The Longest Journey, in Ragnar’s own words, was Gabriel Knight: Sins Of The Fathers — and, unlike me, he wasn’t even a fan of Sierra games in general. That game, however, struck him as being unusually deep, realistic, and well-researched compared to everything else at the time, and he was determined to take all these qualities even further. His game would completely dispense with the idea of a Narrator, transplanting you once and for all inside the conscience of his protagonist — a protagonist who would walk, talk, and react as close to a real human being as possible, even when (especially when) placed in shocking, supernatural circumstances. His universe would be a multi-layered one, with a back history and lore rivaled by RPGs rather than old school adventure games with their annoying plot holes and tons of questions that needed answering but weren’t going to be answered. His way of thinking would be to combine the best aspects of Sierra — intriguing story, epic flair, emotional pull — with the best aspects of LucasArts — humor, satire, and comfortable game design.

An important additional factor is that, while Ragnar might certainly be described as one of the earliest game designers with a well-defined «SJW attitude» — something that became more and more prominent in the Longest Journey franchise as time went by — he is also one of the few who knows how to handle it just right, or, at least, knew back in 1999. With its female protagonist who was simply impossible not to take a liking to (well, unless you were on the Rush Limbaugh level or something), The Longest Journey probably did more for the cause of equity than any other game before it — Tørnquist proudly reported (though I have no idea how he got the data) that about 50% of people who played the game were women, which would typically be reported as an expected and predictable result for something like The Sims, but hardly for a point-and-click adventure game. Something tells me, however, that he would never have achieved this result if the game were merely a blunt, rigid, clichéd piece of feminist propaganda — instead, its moral values are promoted subtly and, in general, take second place to plot, puzzles, and overall atmosphere. His April Ryan does share a lot of features in common with Jane Jensen’s Gabriel Knight — as she does with many other modern fairy-tale heroes, in fact — but in some ways, of course, she is the perfect antithesis of her inspiration, making it rather hilarious to think about how one of the most endearing «sexist» male characters in videogaming was written by a woman, while one of the most inspiring «anti-sexist» female characters in the same genre was written by a man.

Whether The Longest Journey did indeed single-handedly save the adventure game genre from floundering, or whether it was at least tremendously influential on all adventure games to come, are difficult and subjective questions which I am not equipped to answer (for one thing, I simply do not know enough of adventure game history in the 21st century). But at that particular moment, at least, with the game received so enthusiastically at the exact same time that Sierra and LucasArts were both going down in flames, it really might have seemed to be a critical passing-the-baton moment — with a new generation of intellectual European designers continuing to push forward where American boomers had run out of steam. And even if truth is always more boring than myth, I’m certainly ready as heck to keep pushing the myth if it ensures that some people at least will continue enjoying the hell out of this flawed, but wonderful game.

Content evaluation

Plotline

If there is exactly one thing about The Longest Journey that can have me immediately take it down a peg, it is that, for all of his inventiveness, Tørnquist decided to pin it upon one of the most tired tropes in existence — «A Nobody Becomes The Chosen One And Saves The World» (oh why, oh why does it always have to be The World? couldn’t, just for once, it have been the local kebab stand instead?). It is an admirable achievement of his that, having picked that one (and I do believe that video games abuse the shit out of it on an even more casual basis than literature or cinema), he was able to run as far with it as he did. Still, it did cost me a few hours of relative disappointment once the story of April Ryan began to unfurl, and hence a warning: yes, it is a great game with a solid plot, but do be prepared that you will have to be the chosen one and save the world. (And for the record, Gabriel Knight did not have to save the world, he only had to prevent St. Louis Cathedral from collapsing).

In Ragnar’s defense, the world that he did create was, to the best of my knowledge, rather unprecedented in the gaming world; at the very least, in no previous game would that kind of world be laid out in so much detail and with so much care. As the 18-year old aspiring artist April Ryan, you live in the year 2209 AD on one side of The Divide — in our own world, which bears the code name of Stark and is apparently ruled by Logic and Science; meanwhile, the other side of The Divide, bearing the name of Arcadia (why not Shangri-La?), is the domain of Magic and Chaos, and is populated by all sorts of wond’rous races and creatures (no elves or dwarves, at least). Apparently, both worlds were once one, but then Maggie dropped the salt or something, and in order to save the universe from collapsing in on itself and creating heavy metals, Science and Magic were separated from each other, and a special Guardian of the Balance between the two was appointed to keep watch on both sides from an interdimensional hub. Unfortunately, the latest Guardian turned out a little paranoid, and one day abandoned his post without warning — upsetting the Balance and setting up a chain of events that could join the two worlds back together and unleash Chaos upon both, much to the delight of a group of conspirators on both sides («the Vanguard») who had been dreaming of getting things exactly that way for a long time now...

This entire story is told in much, much, much detail some time into the game and, frankly, constitutes its weakest part. There is nothing all that unusual, per se, in the concept of an alternate unseen universe right before our noses, to which certain endowed personalities can «shift» at will (cue Hogwarts and all). What is unusual is that Tørnquist places his starting world two hundred years into the future and has you more or less equally divide up your time between Hogwarts and Surrey, that is, Stark and Arcadia. Thus, The Longest Journey is equal parts cyberpunk and fantasy, defying genre conventions and setting up an interesting precedent — in particular, it allows Ragnar to try out his socio-political models on a conjectured future and a quasi-medieval fairy-tale space at the same time, showing how the same logic is applicable everywhere (in a nutshell: people get angry and pissed off everywhere, and crave for new leaders and new ideas, no matter how risky and dangerous, to help them alleviate their poverty, their boredom, or both).

This already makes for an interesting setting, which makes it easier to forgive the entire line of the «Guardian of the Balance» and the magic disc that you have to reassemble from four or more different pieces. What is even more interesting is that the actual plot of the game is far from predictable. Ragnar is an odd guy with whom you can never tell — one moment he seems to be enslaving himself to fairy-tale clichés, then the next minute he gets busy inverting and deconstructing them. April’s trips between Stark and Arcadia, for one thing, are completely unpredictable — he Shifts her to another dimension when you least expect her to be Shifted, and he can send you off on a monumentally long side quest errand just as you are expecting to get busy with the main quest. Emotional (sometimes corny-emotional) scenes lodge side by side with sarcastic and humorous ones. Secondary characters who seem to be there to help you only end up baffling you, and vice versa.

All of this confusion can certainly irritate a player expecting something more straightforward; check out, for instance, this curious essay on how one found the experience «frustratingly childlike» in its approach. «Childlike» I could maybe agree with, but «frustratingly»? As far as I am concerned, the humor, sarcasm, and occasional breaking of the fourth wall in the game is an essential part of its charm, without which it would play out like one of those JRPGs that take themselves way too seriously and ultimately reward you with a duncecap for suspending your disbelief.

If anything, I actually find the game lacking precisely in those moments when the script goes for too much pathos and forgets to dampen it with enough humor — a case in point is when April first gets to Arcadia, and the local priest gives her a lengthy digest of the entire History of the Balance while using the temple frescoes as illustrative material and the sweeping orchestral soundtrack for emotional support. This sequence is long, confusing, way too serious and hinting that, maybe, the writer has finally bitten off more than he, or we, can chew at this particular moment — especially because we never really saw it coming, since all the previous sequences in Stark, long or short, were well-tempered with doubts, jokes, and witticisms. Fortunately, The Longest Journey does not have a lot of such sequences over its duration (and it is quite a long journey: my complete playthrough that includes most of the dialogue runs well over 17 hours, which is most certainly a record time for an adventure game title as of 1999).

Of course, ultimately everything depends on how you receive the character of April Ryan. Her shtick — which clearly shows a huge Gabriel Knight influence — is in liking to mix seriousness with sarcasm, empathy with humor, and even (sometimes depending on your dialogue choices) humility and submissiveness with self-confidence and arrogance. In other words, she is quite a multi-dimensional human being, and that is what I’d like to be, too, if I ever got caught up in those kinds of situations: deflating fear, shock, and bewilderment with humor. It is true that she does not get to experience a lot of character growth throughout the game, more or less exuding the same mix of sympathetic idealism and humorous cynicism from the first to the seventeenth hour of the playthrough, but since the entire game takes place over several days, it’s not as if she’d be equipped with too much time for this anyway. (And, for the record, she does undergo a complete transformation of her character by the time of the sequel game, Dreamfall — but we shall leave that for its own story).

Empathy and sarcasm alone would not suffice, of course, if they were not properly worded; and the quality of the writing in the game is usually exceptional (for games, that is). The very first sentences uttered by April, as she finds herself stranded on some rocky height in the middle of a recurring nightmare: "Oh no, don’t tell me I’m dreaming, again. You know, for once — just for once! — it would be nice to have a decent night’s sleep without waking up screaming from a bad dream at four AM". Then, looking at the approaching dark cloud: "Even the weather sucks in my dreams. I feel so charmed". Yes, that’s Gabriel Knight all over for you (who also begins the game with a recurring nightmare), but with a tad more internalized focus on yours pretty, as would befit an enthusiastic teenage soul in the late 1990s (not to mention the late 2200s). And she bites, too: after the initial shock of having a conversation with a talking tree is replaced with annoyance at the latter’s condescending remarks ("oh, we do not expect a human to come to our aid"), she snaps back with "lose the attitude, okay?" Thus we have most of the discerning features of the character established in about five minutes.

Complaints about the game often focus on the length of the dialogue: indeed, in his eagerness to bring depth and realism to the screen, Ragnar often goes overboard — for instance, the full conversation with April’s flamboyantly lesbian landlord Fiona, with all the dialogue branches explored, takes up about 15 minutes of voice acting —that’s just one conversation, and quite a lot of it, such as the juicy details of Fiona’s intimate life, is entirely irrelevant to the story; in fact, Fiona herself is but a minor character, who has exactly two scenes in the early part of the game and then reappears only briefly toward the end. But while I could probably agree with the criticism that too many agents are introduced in the early parts of the game whose story arcs are never brought to conclusion (Fiona, her girlfriend, April’s friends Emma and Charlie, etc. etc.), I could not agree that those parts of Tørnquist’s dialogue that are not essential to the story are entirely useless altogether — more than a story-teller, Ragnar is a world-builder, and with two separate planes of existence, the man has got quite a bit of world to build.

Almost every character in the game who has more than two or three lines of text is a distinct personality — even a couple of lazy repairmen whom April has to convince to put together a broken door at the police station (one is lazy, rude, and sexist; the other is lazy and mentally retarded). At least three in particular deserve to be placed in a Hall of Fame for outstanding merits, all of them encountered in Arcadia. One is Abnaxus of the Venar, a flegmatic, frog-like creature whose people manage to exist outside of the dimension of time, which makes it hard for him to communicate in any language that demands obligatory grammatical marking of tense ("It was late, April Ryan. You were tired. We have talked in the morning when you come to visit me" — I’d advise the poor fella to switch to Mandarin, actually). Most likely, he is simply written in because Ragnar wanted to write in somebody particularly unusual, Castañeda-style, but since we are not obligated to revere the guy as a guru or anything, we can just enjoy his perspective in the overall context.

The other one is evil alchemist Roper Klacks, who lives in a stone tower in the middle of a swamp and has to be tackled by April because he imprisoned the wind needed to take her ship where she needs to go. He is quite self-consciously evil in a Monty Python, or maybe even in an Austin Powers, kind of way — as well as a fan of automobiles, telephones, and America’s Funniest Home Videos. This kind of villain is rather inherited from LucasArts than Sierra, and would easily fit into the context of a Day Of The Tentacle — particularly when April has the choice of challenging him to a set of contests, including hopscotch, tic-tac-toe, spelling bees, and Shakespeare recitals, all of which lead to hilarious losses for her. (Silly fussy people who post walkthroughs on YouTube always miss those activities and go straight for the calculator challenge — guys, the game is not called The Longest Journey for nothing!).

Another legend in his own right is Crow, April’s sidekick who, like most sidekicks, is added for comic relief (as if there wasn’t enough comedy without him already!). Lazy, lascivious, politically incorrect, he comes from a long line of Sancho Panzas, and although, other than his being a crow and all, I can hardly think of anything that makes him particularly unusual in that line, he just does a good job of deflating April’s ego from time to time, as well as faithfully playing out the Taoist image of the Least Significant Being in the Universe Making All the Difference. That said, the efficiency of his character probably has more to do with his voice actor than his spoken lines, so we’ll get to that in its proper time.

Special mention should be made of the game’s finale, which I won’t spoil for those who have not played the game; let’s just say that Ragnar is not much of a fan of happy endings (neither am I), and I can think of few other games in which the act of saving the world left behind such a sharply pronounced feeling of dissatisfaction. I mean, people would go on to curse the ending of Mass Effect in large part due to the unavailability of the «and they lived happily ever after» option, but at least BioWare made sure that the galaxy was saved in a truly Monumental Fashion; you could be indignant about your own insignificance, but you could not deny the atmospheric importance of the moment on a grand scale. In The Longest Journey, the saving of the world is done so casually that you hardly even notice. You might as well just have saved that kebab stand. But the trick is that you will be feeling empty and dissatisfied along with your title character — empathy on the prowl — and that will most certainly get you thinking about whether saving the world is really worth it, as well as the balance between individual importance and freedom of will, on one hand, and destiny / karma, on the other, that sort of thing. Morale of the story: if you absolutely do have to have yet another round of gratuitous world-saving, at least make sure that you got absolutely nothing out of it. Maybe next time you’ll think twice before listening to creepy old men and overrating the importance of your nightmares.

Puzzles

In later years, when Ragnar would design the sequels to The Longest Journey (Dreamfall and Dreamfall Chapters), he would be consciously drifting away from the 1990s adventure game model, focusing almost entirely on the story and downgrading the actual challenges to an almost elementary level. The original game, however, was still very much aware of its point-and-click adventure nature — and although I get the feeling that Ragnar himself was getting caught up so much in the story that the difficulty of the puzzles curvaceously dropped all through the game, the first several chapters present quite substantial obstacles on your way to restoring the Balance. Nothing particularly unusual about them — most of what you have to do is related to finding stuff and manipulating it one way or the other — but the same kind of criticism that is commonly applied to classic Sierra and LucasArts games is just as easily applicable to The Longest Journey as well.

At least one of the puzzles — the infamous Rubber Duck Challenge — has probably been featured on every worst-of list of challenges in adventure game history (which is good, because The Longest Journey still needs all the publicity it can get). At one point early in the game, you need to get an electrified key off the subway rails in order to use it in a completely different location, and to do that, you need a bit of rubber and some leverage. Any normal person, of course, could have simply bought a pair of rubber gloves, but since the city of Newport seems to be strangely devoid of general stores, you shall have to do with whatever is lying around, and concoct a pretty grotesque device to achieve your goal.

That said, you could at least theoretically imagine your rubber duck device existing and functioning in the real world — you’d probably have to go through several months of training to learn to use it properly, but it could exist. To me, far more logic-defying is yet another frustrating puzzle from the same chapter, when you have to get a rather dim-witted movie theater employee out of your way by tricking him with a toy monkey (called «Constable Guybrush», by the way) and some additional paraphernalia — I remember having far more trouble with that puzzle just because I could never bring myself to believe that the answer would be on that level of phantasmagoric. What makes the whole thing even more unpleasant is that the preceding parts of the game roll along smoothly and do not in any way prepare you for this level of difficulty or absurdity — and that both the Rubber Duck puzzle and the Constable Guybrush puzzle are only necessary because you have to sneak inside a movie theater... when you could instead have simply bought an entry ticket or something.

Fortunately, once you have your first Shift and finally get to Arcadia, such situations are trimmed down to a minimum, and the game becomes much more balanced and logical on the whole, while still retaining a reasonable level of difficulty. Every once in a while, Ragnar introduces a «special» puzzle — such as finding your way in the cheating maze of Roper Klacks’ castle, or building a magical telephone line on the island of Alais — but these are original and fun to do. Sometimes success depends on whether you have done enough reading (in the Marcurian library) or talking (do have patience and try to exhaust most of the dialogue trees with your talkative NPCs — it is often impossible to progress without doing so), but this is more a matter of diligent perseverance than anything else.

In strict accordance with the classic LucasArts codex, Ragnar makes sure that the game can never place you in an unwinnable state — even despite lots and lots of traveling from place to place, April can never technically end up anywhere where she is not in possession of or cannot pick up an object required to complete her next objective — and that you can never die, not even in the direst situations. The latter is actually weirdly unrealistic: for instance, in one case you end up locked inside a small tree house with the local Baba Yaga on the prowl, and both of you will simply end up standing opposite each other, with the game waiting indefinitely until you complete the required action to win. Similarly, you cannot drown, get burned, be captured, be devoured by the Chaos Storm — all of which is convenient for the player, but detrimental from an atmospheric perspective, since it essentially transforms both Stark and Arcadia into completely safe zones, while story-wise, the game is constantly trying to tell you exactly the opposite. This is one aspect of the game that Ragnar probably realized was wrong himself, since he would fully reinstate the possibility of dying for Dreamfall.

Finally, the LucasArts strategy is also adhered to in dialogue trees, where the player often has a choice of replying in several different ways — yet the choices almost never matter, apart from just one decision, taken early in the game, which will lead you to go through one out of two possible supernatural experiences. Most of the time, the different options are only there for you to build a slightly more appropriate personality for April; you can react more rudely or more politely, with more sympathy or more sarcasm, more inquisitiveness or more indifference, etc., the final outcome will, as a rule, always be the same. (There is a curious moment when one of the characters, the disgustingly foul-mouthed but helpful Flipper, promises you to reveal more of his backstory if you truthfully answer his question of "are you a virgin?" — and although both "I am a virgin" and "None of your business" are both options, apparently the required answer is "I’m not a virgin", as it is the only one that will get the guy to disclose himself to you. Apparently, Ragnar believes that for an 18-year old to remain a virgin in 2209 is beyond believability — in which case one could, of course, wonder why the hell would the Flipper even bother to come up with the question). But at least it makes for a tiny bit of replay value.

In any case, a few specific complaints aside, there is no question that The Longest Journey is indeed a game, not just an interactive movie experience — and a pretty solid one as far as adventure game rules / logic are concerned. This might turn into a problem if you are enraptured with the story (and I wouldn’t blame you), but, fortunately, the most difficult puzzles will be there for you before you get the chance to become fully enraptured, so, all in all, Ragnar Tørnquist may be fully deserving of his own title — Guardian of the Balance.

Atmosphere

As I already mentioned, the most unique feature of The Longest Journey is that it combines two distinct genres — cyberpunk and fantasy — in hopes of making you yourself feel all possible parallels and distinctions between the two. Both of Ragnar’s imaginary worlds, Stark and Arcadia, are clearly influenced by (and, in parts, copied from) various sci-fi and fantasy works, yet both also strive to be original enough for us to at least respect, if not necessarily admire, the attempt. At the very least, the universe of The Longest Journey cannot be called «generic»: it is a focused artistic creation, rather than merely a convention for testing out playing strategies and solving puzzles.

Of the two worlds, be it here or in the Dreamfall sequels, I must say that I always prefer Stark. Arcadia, the land of Magic and Chaos, is imaginative enough, but much too often, it just seems that the author’s main concern here was about how to make this place not seem like any other magic place ever created. Hence, no generic elves or dwarves — in their place, we get the blue-skinned exotic Dolmari (fortunately, this was ten years before Avatar), the genetically-related but evolution-separated aquatic Maerum and aerial Alatiens, and the faceless Dark People, who look like a more talkative and bibliophilic variant of the Dementors. But despite all of Ragnar’s noble efforts, Arcadia still does not end up looking that much different from the average fantasy / fairy-tale world out there (honestly, there’s just so many of them that conjuring up a fully original one even in 1999 would be akin to trying to write a completely original three-chord punk rock tune). An evil wizard turning people to stone, an ugly old hag luring innocent travelers to her house for dinner, a sea monster speared by a brave hero... now where exactly have we seen all this before?

It is perhaps most obvious when you get to the Alatien village where you have to listen to four lengthy folk tales in order to get the correct answers for an audience with the Elder — all of them are variations on traditional motives (such as the myth of Icarus), albeit with a noticeable feminist flair (such as the Icarus in question being a girl, which does not save her from sharing the same fate). They certainly aren’t irritating variations or anything; it’s just that it is hard for me to fall in love with Ragnar’s Arcadia as a whole. Specific characters can be wonderful, such as Abnaxus or the gentle giant Q’aman with his Zen attitude ("Man, you got relaxing down to a fine art!" – "Q’aman not be knowing anything about fine art. He be a philistine"), but the world as a whole is nowhere near as impressive as, say, Tim Schaefer’s Land of the Dead from Grim Fandango, which came out only one year earlier.

Tørnquist’s «Stark», however — essentially our own world two hundred years into the future — is a completely different matter. It is an extremely interesting half-utopian paradise, half-dystopian nightmare, which also has lots of literary and cinematographic parallels (comparisons to Blade Runner are fairly frequent), but does not quite ideally fit in any of the models I am familiar with. The game begins in «Venice», a charmingly dirty bohemian area of the bigger city of Newport (April: "Rust is the very definition of Venetian architecture. Venice wouldn’t be the same without the rust. It would be better, but not the same") populated by free-thinking spirits and peppered with cool bars and art schools — yet the first object in April’s reality with which she can have a conversation is a «friendly» voice communication terminal who, upon learning that she does not have sufficient funds, warns her to "refrain from voice communication in the future, or you will be reported to the F.U.B. and charged for processing time" (April: "F.U.B.?". Terminal: "Fair Use Bureau. They are authorized to carry deadly arms").

This three-way contrast between intoxicating creative freedom, impressive technological progress, and vigilant police state defines everything in Newport (and, it may be assumed, Stark in general). Apparently, the world is run by a tight alliance between corporate interest and security forces, to the extent that, as a semi-friendly cop consents to explain to April, "the police department is a subdivision of the Bokamba/Mercer Company and the Bingo! Corporation" (April: "Doesn’t that constitute a conflict of interest?" Cop: "Not if we don’t arrest any employees of either company"). Class segregation is rampant (April will even have to get a special ID to take her where she needs to go in the end), drug addiction in crime-ridden quarters is worse than in the city of Baltimore, yet in all the spheres that are not necessarily tied to corporate activity, there is total freedom — freedom of creativity, freedom of worship, etc. And technological warfare, in which government and corporate agencies battle brave little hackers protecting individual freedoms, runs deep and wide.

This angle, as you can probably already see from bits of dialogue, allows Ragnar to drag in a lot of sarcastic humor, most of which actually works — maybe even too much humor, since in his next games he would continue to depict Stark in a more serious light, leaving most of the humor to specific select characters. Interacting with this weird world as April, poking fun at its inconsistencies, bureaucratic stupor, and undercooked artificial intelligence, is a gas — there is, for instance, an extremely easy-to-miss sequence where April tries to get inside the police station through the front door (most people just go for the covert entrance right away) and is stopped by a cop who is an actually an actor practicing for his next role, but was still hired for the job to save the powers-that-be a bit of expenses (Cop: "I’m not a weirdo! I’m an actor!" April: "No offense, but... isn’t that an oxymoron?"). A sequence that is impossible to miss is one where poor April has to go through the hellish procedure of getting just the right official form to get the couple of repairmen off their lunch break (Police lady: "The 09042-A? Why the hell didn’t you ask me for that one in the first place?" April: "Because I’m a cruel bitch, and I love torturing you. In fact, I’ve made it my life’s mission to haunt you forever and ever with requests for useless forms and documents.") And just wait until April finally makes it to Colonial Services, where people are essentially taken away to nearby asteroids for a lifetime of indentured servitude ("how does it feel to work for the Dark Side?")

As dark-humorous and parodic as it all seems, Ragnar’s Stark might, in fact, be one of the most believable portrayals of our not-too-far-removed future (next to all the zombie apocalypses, of course) that I have seen in the world of videogames, so it is hardly surprising that I have really enjoyed spending quite a bit of time with April in Stark, and could not help but be a little sad every time she got whisked away to another adventure in Arcadia. To make things even more snappy, Ragnar sometimes inserts his ideas on how history — even recent, 20th century, history — shall eventually become compressed and flattened out in the minds of people of the future: thus, one of the game’s main characters, the mysterious old Cortez, is introduced as a fan of «old movies», so April has to seek him out at a vintage movie theater, where she can read the titles to some of the movies and share her ideas with us ("‘The Maltese Falcon’... oh yeah, I remember this one. It’s a Disney cartoon about a falcon who, uh, goes looking for a black cauldron... it’s got singing mice in it, I think... I mean, don’t they all?"). Or, when she gets her hands on an old pocket calculator that somehow made its way to Arcadia, she mentions something about "Elizabethan times", and it would be rash to think that she actually meant Elizabeth II.

Precisely because the game is so fun and sharp whenever it is taking a satirical turn, I am less pleased when it tries to take itself more seriously. In particular, all that mumbo-jumbo about the Balance, the Guardian, the Draic Kin, the Vanguard, the magic disc, etc., essentially most of the «core lore» of the game, could take a hike for all I care — for all I know, it is only there to give you an excuse to travel from place to place, meet colorful characters, and be proud of yourself for earning achievement after achievement (by the end of the game, April will be able to introduce herself as «The Wave», «The Windbringer», «The Waterstiller», «The Venar Kan-ang-la», and «Bandu-embata of the Banda», earning more titles than an Achaemenid King of Kings). The game is always at its best not when it tries to be pathetic and monumental, but cozy and homely — Ragnar is just so much better at writing the first half of Fellowship of the Ring than Return of the King, if you get my drift.

Still, all is forgiven with the game’s final act, which could have included a lot of drama and cheesy epicness, but instead prefers to offer a surprisingly chamber-like conclusion; at one point, it unexpectedly jumps into psychologically disturbing territory (the vision of April’s Dad — not a particularly pleasant spectacle for those who are easily shocked and offended), and then, as I have already mentioned, leaves our poor protagonist at a crossroads with absolutely no idea of what to do next — with the dialogue, the music, the visuals beautifully (if the word ‘beautiful’ is applicable here at all) conveying this feeling of emptiness which you get when you get your job done to no gratification whatsoever. It acts, at the same time, as a hook — you know you desperately need to get back to this world, because this cannot be and will not be the end, not by any physical means — and as a harsh reminder about "what does man gain by all the toil at which he toils under the sun?" It is easily the least satisfying and the single best ending to an adventure game up to that point — well worth enduring all the puffed-up lore for.

In conclusion, it should be added that most of the atmospheric qualities of the game are provided by the writing — and the voice acting: as we shall see below, The Longest Journey is quite flawed (even for its time) when it comes to the visual aspect, which, unfortunately, will be an immediate turn-off for many players, particularly those who like to complain about the length of the dialogue or the «immaturity» of the title character (because, apparently, having a sharp sense of humour and irony is seen by some people as «immaturity»). But if you are willing to look past the technical flaws and concentrate primarily on the substantial virtues, the universe of The Longest Journey will be genuinely hard to forget.

To be continued…