«Incidental music» is almost as much of an offensive term as «accidental music», basically implying that, whatever happens, there can hardly be a valid reason for listening to this kind of music on its own, outside of non-musical context for which it serves as relatively lowly, forgettable by-product. And like every stereotype that ever managed to take hold of collective consciences, it is not entirely untrue — rather, it is a notion which correctly applies to many (if not the majority of) encountered situations, but with those few situations to which it does not apply being at a terribly discriminating disadvantage.

I have actually listened to quite a few «OSTs» on their own in my lifetime, but mainly out of general curiosity and/or respect for the visual media they accompany. John Williams, Bernard Herrmann, Nino Rota, even Ennio Morricone — all of these gentlemen have produced their fair share of genius themes, contributing immensely to the cumulative effect of the respective films, but I do not ever recall myself thinking, "hey, I’m in the mood for some Good, Bad & Ugly music today", or, "it’s been a long time since I enjoyed those lush strings of Vertigo, let’s throw it on real quick". There’s something slightly shameful about it, because, let’s face it, what is it exactly that makes something like ‘The Imperial March’ a lesser piece of work than any solid instrumental hit on the pop market from the last 70 years? (It may certainly be "lesser" than Wagner or other great classical composers who influenced the Hollywood styles of composing, but then, pretty much everything is "lesser" than Wagner, so this comparison simply does not count). It’s just that somehow our mind has decreed that ‘The Imperial March’ needs actual storm troopers to reach its full potential. If you visualize it differently, it becomes parodic, or, at least, "meta" in a culture-playing manner.

(On a side note, this can also work unpleasantly in reverse: choosing non-incidental, original music, especially great original music, as part of your movie soundtrack can actually cheapen its impact, as if you’ve selected a superior piece of equipment to deliberately perform an inferior function. This is why, for instance, I’m not a huge fan of Scorsese always relying on Rolling Stones’ and other classic rock artists’ back catalogs for his movies — I mean, I want to enjoy ‘Gimme Shelter’ on its own, not subjugated to some other pretentious dude’s artistic ambitions.)

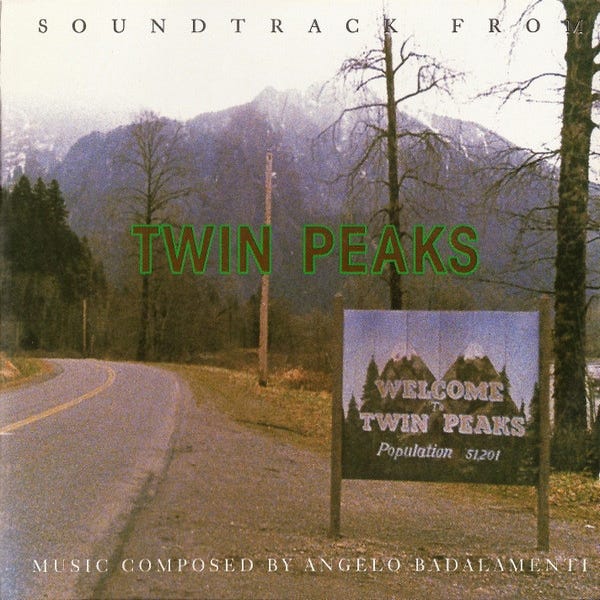

Ironically, the one and only OST in my life to which I regularly find myself returning for its own sake is also the one that, in most people’s minds, is completely and utterly inseparable from its visual context. Without a doubt, I have certainly listened to Angelo Badalamenti’s Soundtrack From Twin Peaks many more times than I have watched the show — like any good child of the 1990s, I love Twin Peaks, but not nearly enough to loyally rewatch it every year (or, God forbid, waste kilotons of time trying to «decode» its «message», which I approach from a simple scientific point of view: what is easy to understand about David Lynch’s vision should be fairly evident from the start, and what is difficult to understand about it most likely means that it never existed in the first place and is just an empty slot upon which people are free to project their own fantasies and complexes if they got nothing better to do). The music, however, managed to achieve the impossible — like The Shadow from Hans Christian Andersen’s tale, it eventually detached itself from the shackles of the visuals and became an artistic treasure in itself for me. It’s on my antiquated Ipod, it’s in my aging head, and it still gives me its own autonomous impressions, rather than merely triggering memories of how the owls are not what they seem and that gum you like is going to come back in style (somehow I’m already beginning to doubt that).

The reason behind this is simple enough. There is good music and there is bad music, there is innovative music and there is formulaic music, there is stimulating music and there is perfunctory music — and then, every once in a while, there is music that goes where the hell did THAT come from? — music that happens to be a totally unique, spontaneous, inimitable result of some marvelous combination of circumstances; an auspicious juncture of the general Zeitgeist with several individually brilliant minds.

Case in point: Angelo Daniel Badalamenti, a proud descendant of the Italian tradition and a lucky son of Brooklyn, was a talented composer of film music, and his soundtracks both for David Lynch movies, from Blue Velvet to Mulholland Drive, and for other films (like Jeunet and Caro’s classic City Of Lost Children), have always garnered lots of just praise. But none of his work even begins to compare with the music he composed and recorded for Twin Peaks. Nothing ever made in this world really sounds like the music made for Twin Peaks. No rightful comparison can be made. No rightful comparison will do it proper justice. No comparison can be found that will not diminish and demean the sensual and emotional significance of that (relatively small) bunch of tracks.

Of course, without David Lynch it would never have happened; we know that the soundtrack was created by Angelo in close collaboration with his friend, feeding upon the mental images Lynch was creating (there’s a great video of Badalamenti describing the process of creating ‘Laura Palmer’s Theme’, step-by-step, and I can only hope that it all really happened exactly according to his description, because it’s almost too frickin’ cosmogonic to be believable). And we do realize that everybody involved with the creation of Twin Peaks in 1989-1990 understood pretty damn well that it was the start of a new era — an era in which complex and mysterious arthouse values would come down from the skies to inseminate one of the most popular and «simplistic» forms of artistic media, with Twin Peaks serving much the same purpose as Sgt. Pepper did for the music world two decades earlier. And it still does not fully explain how the music of Twin Peaks came about, and how it sounds like nothing else ever done.

Even if you go back just a few years, and think of the «countdown to Twin Peaks» as starting out with the Julee Cruise-sung ‘Mysteries Of Love’, included in the soundtrack to Blue Velvet, it’s still comprehensible: this is ambient-ish dream-pop, very much influenced by the likes of the Cocteau Twins or This Mortal Coil. Atmospheric, romantic, not particularly catchy, not particularly ingenious. But then in 1989, when Cruise releases her debut album, all of it written by Lynch and Badalamenti, almost as a teasing «preview» of what Twin Peaks is going to be all about, you get ‘Mysteries Of Love’ side by side with ‘Falling’, and the difference is huge.

You can find plenty of musicological takes on ‘Falling’ (= ‘Twin Peaks Theme’ without Cruise’s vocals), ‘Laura Palmer’s Theme’, and the rest of all that stuff scattered around both in printed sources and on the Web, and they will all reasonably tell you that the music is essentially a synthesis of old-school lounge/cool jazz, «exotica», pre-Beatles pop standards, ambient, and late Eighties’ electronic production values. But much like any explanation of life, focusing on the careful enumeration of all the aminoacids that constitute it, kind of fails to explain what it is that actually makes all those aminoacids tick, so does any clinical examination of the components of Twin Peaks’ music fail to explain what it is that makes all these disparate elements so efficiently create an alternate universe of their own.

In trying to move a little closer to the ultimately unknowable truth, let us, for the moment, eschew the two main themes — the ones which will probably be recognizable forever from their first couple of notes to anybody who watched the show even once — and concentrate on the ever-so-slightly less well remembered classic ‘Audrey’s Dance’, which, as the title suggests, should indeed be primarily associated with the character of Audrey Horne but actually crops up in all sorts of different places and moments. Unlike the two main themes, which are certainly «mood pieces» but still manage to tell some sort of dynamic story (and generate an appropriately cathartic feel each time they play), ‘Audrey’s Dance’ is a mood piece (rather than a soul piece) through and through, mostly staying in the same place throughout its duration, relying on slight, subtle shifts to assert its ambience. It’s pure «elevator music» — except that something about it often makes me want to just ride that elevator forever, and never get out. Let’s take a closer look.

At the core of the magic actually lies a very basic Fifties’ progression — in fact, just tweak a couple of those opening synth-vibraphone notes and you get ‘Framed’ by the Coasters (or, rather, the Sensational Alex Harvey Band, who took that song at a slower tempo, comparable to this arrangement). Even the finger-snappin’ rhythm, about which the Lynch/Badalamenti production team was not so sure from the start, reinforces that Fifties’ feel. But, on the other hand, where and when in the Fifties are you going to hear that chord progression played on a vibraphone, or, precisely, on a (pseudo-)vibraphone with so much reverb that it seems to use your own head as a resonator? And most importantly, who would think of resolving, I mean, suspending that chord progression with a tritone — the Devil’s Chord itself? This is not just the Coasters; this is the Coasters meet Black Sabbath and get married by Brian Eno, and it still gets pretty clinical as a description, and it’s only the first five seconds.

What follows is a five-minute trance in which a walking bassline and the eternally suspended vibraphone form the foundational thread of life, against which assorted clarinets and saxophones roam in some sort of Brownian motion, echoing either Ravel or Duke Ellington or both at the same time, but ultimately forming a sort of «primordial musical soup» — not exactly frightening or empathetic, just enigmatic through the very fact of their all being there and not doing much of anything except roaming.

My own mental impression is simply being stuck in some sort of alien world, hemmed in on all sides by weird specimen of the local multi-cellular fauna — seemingly harmless for now, but making you scared shitless all the same, as in, «make one wrong move and these weird life forms will tear you limb from limb». And they are definitely not uniform, homogeneous specimen: the clarinets are jellyfish-shaped herbivores, mooing and grooving all over the alien prairie in search of elementary nourishment, while the intrusive saxes, going QUACK QUACK QUACK!! from time to time, are small, but hungry birds of prey swooping down from the skies in regular, recurrent patterns to feed upon the clarinets. Really weird sonic combinations out there.

By the middle of the track, the roamin’ and gloamin’ becomes so intense it can drive you mad — it’s as if you’re passing through the very heart of this creepy wilderness — but then it subsedes again, and the last two minutes slowly reassure you that whatever danger there might have been, you’re probably making it out of this place alive and in one piece. Probably. No wonder Audrey Horne, the show’s principal «troublemaker», is supposed to feel so attracted to this piece — it’s not just dreamy, in her own words, it’s provocative as heck, too.

See, the thing here is that there have been gazillions of «weird alien soundscapes» recorded over the decades. There have been entire albums dedicated to such stuff, from Amon Düül II’s Tanz Der Lemminge to Brian Eno’s Another Green World and far beyond. But with most of that stuff, the emphasis would always be on the unusual elements — new ways of extracting sound, new use of chords, new production techniques and stuff; to «do alien», you needed to «think alien», suggest all sorts of futuristic sci-fi decisions that always ran the risk of clicking or non-clicking with the audience. Nobody would say, «oh, let’s just take an old Miles Davis / Platters / Roy Orbison number and make it sound like it came from the neural networks of green amoebas in a galaxy far, far away». Or maybe somebody said that every once in a while, but nobody was able to deliver as fully on the idea as David and Angelo did with these little bits. Maybe it is simply this combination of deep familiarity with even deeper mystery that makes all these tracks so mind-blowing.

Again, returning to the connection with the show itself, it’s clear how the duality of the music perfectly correlates with the duality of the visual medium — whose prime task was to make you live out the connection between the mundane / familiar / old-fashioned and the supernatural / impenetrable. But I reiterate: as perfectly as the music works within the show, it also has its own, autonomous, fuller impact, which is best felt if you actually listen to the soundtrack separately from the movie. A composition like ‘Audrey’s Dance’ is never heard completely, without interruptions, in all of its psychedelic, trance-inducing glory, within the confines of Twin Peaks itself, as «iconic» as it feels when actually accompanied by the image of Sherilyn Fenn slowly swaying on the checkered floor of Norma’s diner. (Is she seeing all those green amoebas inside her head, too, the way I see them, I wonder?). The same, of course, applies to everything else on the soundtrack — even supposedly fillerish tracks like ‘The Bookhouse Boys’ and others, as they all serve their collective purpose.

As for the stand-out status of Soundtrack From Twin Peaks from the rest of Angelo’s output, I think the closest analogy I can think of is Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Jesus Christ Superstar — with Sir Andrew writing it in that brief, fortuitous time window when even «outside» people like himself could express their artistic ideas in the fresh, exciting language of rock music; nothing else he ever did comes within a ten-mile radius of the cathartic heights of JCS, as he intentionally switched to other, more old-fashioned and conventionally-corny musical codes. Likewise, the Lynch/Badalamenti collaboration occurred at a particularly fortuitous time — the grand artistic shake-up of the late Eighties / early Nineties, with people (some people, at least) waking up from the glossy, technological, sci-fi stupor of the Eighties while at the same time recognizing the melodic and atmospheric contributions of that decade to our musical stocks. And Twin Peaks itself was precisely that — the juxtaposition of old-fashioned coziness with magical modernity, fortunately, presided over by people with good taste and a deep, deep understanding of what is so great about both the old and the modern values.

I'd never heard of this composer. He was apparently born in the 30's, predating the Beatles, and seems to have dabbled with a career as a corporate songwriter for some commercially oriented artists in the mid 60's. I've listened to some of these songs mentioned on wikipedia, and I can't really find anything exceptional about it. How strange for him to have created a whole new sound at the age of 52 after a career of mediocrity.