Jacques Brel: Au Suivant

I suppose that, outside of the Francophone universe, most people’s awareness of anything Brel-related rarely extends beyond a bunch of cheesily glossified covers like Terry Jacks’ ‘Seasons Of The Sun’. Those who take their music listening somewhat more seriously are likely to reach out to Jacques through David Bowie’s covers of ‘Amsterdam’ and ‘My Death’, or perhaps even through Scott Walker’s numerous covers on his first three solo albums from 1967–1969 — all of those suitably Anglified through a set of original translations by Eric Blau and Mort Shuman; Shuman’s role in popularizing Brel for English-speaking audiences, in particular, can hardly be overrated, as he was behind the 1968 off-Broadway musical Jacques Brel Is Alive And Well And Living In Paris, a major critical, if not commercial, success that, for a little while, made Brel almost a household name in American intellectual circles.

Speaking more specifically of European audiences, and even more specifically of Russian ones where my knowledge is a bit more grounded in personal experience, the situation is somewhat different since French popular music has always enjoyed a lot of success and recognition here — in the post-Stalin Soviet Union, along with Italian pop, it was imported as fodder for the starving masses on a much larger scale than anything rock’n’roll-related — but the French scene has always existed here in two class-stratified incarnations. The hoi polloi share of the market was represented by the chanteuse lineage going from Edith Piaf to Mireille Mathieu and then to their later descendants (e.g. Patricia Kaas, whose Mon mec à moi followed you everywhere like a nightmare in the early 1990s), and, on the male front, by figures like Charles Aznavour and Joe Dassin. Some of that stuff has, perhaps, aged a little better than one might suspect — like, say, the Carpenters in the States, once regarded as the ultimate achievement in glossy, cheesy blandness, but now generally redeemed on the strength of Karen’s musical talent and tormented persona — yet on the whole, the general lack of grit and overabundance of suaveness would make most of the scene unpalatable to the «selective» music lover.

On the opposite side of the scale were people like Brel and, perhaps even more commonly, Georges Brassens — the darlings of the philologically-oriented girl students taking French and guitar lessons. This was «the other side» of French pop: never seen on TV, rarely, if ever, buyable in music stores, and 100% appealing to those who craved deeper lyrics and less groomed ’n’ polished artistic attitudes. It was largely the same distinction as existed, say, between the pop lovers and the folkies (or modern jazz enthusiasts) in early 1960s’ USA — a distinction that paid less attention to the actual quality of the music and far more to its «class parameters», so to speak.

My own wary attitude toward such class distinctions back at the time kind of resulted in me paying little attention to either of the two camps, and in the end, my personal encounter with Brel brought me back full circle to where this text begins: David Bowie’s cover of ‘Amsterdam’, which left me fairly indifferent — followed by The Sensational Alex Harvey Band’s cover of ‘Au Suivant (Next)’, which, conversely, rocked me to the core. It is largely in honor of that cover that I’ll try to write a little bit about Brel, specifically focusing on ‘Au Suivant’ rather than any other one of his achievements; otherwise, it’d be a really tough choice, given the man’s superior consistency over his two decades of songwriting.

First and foremost, much like Bob Dylan, it would be weird to assimilate Brel without paying attention to the lyrics — an obvious impediment to all those who missed their French lessons in junior high — but it is absolutely not an impossibility. Although Brel was not much of a musician himself, he was musically gifted, had a great ear for melody, and was regularly surrounded by expert musicians; unlike Brassens with his solitary acoustic guitar, Brel’s arrangements are typically complex, often involve pseudo-baroque orchestration, and regularly get by on mood and atmosphere alone, without the necessity to clarify what exactly he is talking about. And while Blau and Shuman’s translations of his poetry are masterful in their own right, they occasionally mislead from the trail, as is typical for just about any first-rate poetic translations — so I wouldn’t necessarily say that listening to Jacques Brel Is Alive And Well will improve your understanding of the man’s artistic spirit as compared to the situation where you only listen to the originals without literally understanding a single word.

Second, I’m fully bypassing the «French vs. Belgian» angle here: apart from Brel’s decidedly non-Parisian articulation (he rarely rolls his r’s like any respectable French singer is supposed to by definition), his occasional switching to Flemish (which wasn’t his native tongue anyway), and some inevitable autobiographical details that crop up in many of the songs, I couldn’t really tell which major features identify the man as a «Belgian» rather than «French» artist (and most of his artistically relevant years were spent in Paris anyway). It does feel, though, as if Brel’s art occupies a somewhat intermediate place between what we might identify as «quintessentially French» (chanson) and «quintessentially German» (Kabarett) music, Maurice Chevalier-meets-Kurt Weill sort of thing, so perhaps that’s that — the sweetness comes over from the French side, the bitterness and humor from the Germanic, and they both meet halfway in Belgium. But these are, of course, just crudely overgeneralized approximations, not to be taken more seriously than they deserve. Besides, if our continued mission is to keep the spirit of Brel «alive and well» world-wide, who really cares about how much he embodies the Belgian spirit? Let’s leave cartoonish battle-of-the-nations stuff to the 19th century (or its modern revivalists, like certain contemporary leaders of the largest countries in the world that we won’t be naming for reasons of taste and courtesy).

‘Au Suivant’ (first came out in 1963 on the mini-album Mathilde, but most people probably encounter it nowadays on 1966’s full-fledged LP Les Bonbons) is a fine example of that half-French, half-German style, one that would not, as it seems, feel completely out of place in a Kurt Weill opera (and in terms of mood and sentiment, if certainly not actual music, strongly reminds me of Berg’s Wozzeck — the miserable protagonist of the song could, in fact, easily be a Wozzeck-like figure himself). Its bizarre properties begin with the rhythm — somewhat militaristic, on one hand, with the «army drum» setting a marching tone, but also syncopated in an almost tango-like manner, creating the feel of a danse macabre... but also quite gently arranged, with pianos and glockenspiels and string crescendos, though whether that glockenspiel is supposed to represent a celestial vibe or a skeleton dance is up to you to decide. It’s also a good example of the classic Brelian crescendo, gaining in intensity with each new verse (including, for instance, an ecstatic jazz saxophone breaking in out of nowhere two minutes into the song) and becoming a musical maelstrom by the end.

On top of that, Brel delivers a set of fictional «recollections» of the protagonist’s army life which have often, in various descriptions I’ve seen on the Web, defined as «the story of losing your virginity to a prostitute in an army brothel» — which is about as accurate as describing ‘A Day In The Life’ as «the story of an unfortunate traffic accident». Quite possibly, this is a result of the (involuntary and inevitable) imprecision of Blau and Shuman’s otherwise excellent translation: in the original’s first verse, Brel is clearly talking about a queue into the men’s showers — j’avais le rouge au front et le savon à la main (literally «I had red on my face and soap in my hand», a nicely zeugmatic turn of phrase) — meaning that the reference to the bordel ambulant in the next phrase is just one more episode in a series of traumatic events. In the translation, however, there are no references to ‘soap’ whatsoever, so you sort of get an embarrassingly hilarious vision of a queue of naked men lining up to be served in a "mobile army whorehouse" ("I followed a naked body and a naked body followed me" — a great line anyway).

The bottomline is that ‘Au Suivant’ is, at the very least, a general sprawling lambasting of the military way of existence — and at most, a desperate lashing out against any system designed for de-individualizing the individual: hardly the most unique artistic stance in the universe, but quite outstanding in terms of execution. Brel himself served in the Belgian Air Force from 1948 to 1950, but I seriously doubt the Belgian army relied on "mobile army whorehouses" by that time, so the depiction is fictionalized — more applicable, perhaps, to circa-World War I practices than to later eras — and in any case, the whole thing is to be understood as one large, fat metaphor. I mean, the song is easily relatable for anybody who ever stood in a long bureaucratic queue. It is not the reference to losing your virginity ("je me déniasais") anyway that serves as the key point of the song — it is the many, many different ways in which Brel delivers the title of the song: au suivant! au suivant! au suivant! imitating the angry, or impatient, or condescending, or stultifyingly bored intonations of the insentient bureaucrats with whom each and every one of us has had a lot of personal experience.

Comparing the original French lyrics and the classic Blau/Shuman translation back to back, I can’t help but feel that the translators made the song a bit more angry than it was meant to be originally, reflected even in such minor details as "cette voix depuis je l’entends tout le temps... cette voix qui sentait l’ail et le mauvais alcool" (literally "this voice, from then on I hear it all the time... that voice which smelled of garlic and bad alcohol") becoming "it is his ugly voice that I forever hear... that voice that stinks of whiskey, of corpses and of mud" — ‘ugly’, ‘stinks’, and ‘corpses’ have all been thrown in for emphasis, even if it could simply have been "that voice that smells of whiskey, of garlic and of mud".

A particularly telling distinction is perhaps the most brilliant couple of French lines which, unfortunately, had to be erased in the translation because, apparently, they would not be easily understandable to American audiences: "Ce ne fut pas Waterloo non non mais ce ne fut pas Arcole / Ce fut l'heure où l’on regrette d'avoir manqué l’école" — "this was not Waterloo, but it wasn’t Arcole [either], it was the hour when one regrets having missed school", with references to Napoleon’s greatest defeat and one of his greatest triumphs. In the translation, this becomes "Oh, it wasn’t so tragic, the high heavens didn’t fall, but how much of that time I hated being there at all" — no place here for Arcole, only Waterloo, and the second line becomes more straightforward and far more bitter-hateful than bitter-ironic in the original. Not as classy, in my opinion, but still somehow managing to preserve the gist of it.

In one particular spot, though, I think the translation actually manages to improve on the original — the final suicidal verse, the apex of the protagonist’s desperation: "Un jour je me ferai cul-de-jatte ou bonne soeur ou pendu, enfin un de ces machins où je ne serai jamais plus le suivant" (literally "one day I’ll make myself a legless cripple, or a nun, or hang myself, one of those things where I won’t ever have to be ‘next’") becomes "One day I’ll cut my legs off or burn myself alive, anything, I’ll do anything to get out of line to survive", with the brilliant description of burning myself alive as an act of survival, sort of implied, perhaps, in the original but not spelled out directly. The burn myself alive thing, though, once again contributes to the overflowing level of agitation that Blau and Shuman piled on top of the already barely stable Brel original.

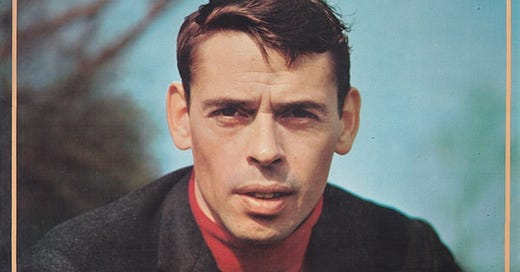

That original itself used to become even less stable in concert: playing back-to-back versions of the original studio recording with a 1964 live performance from L’Olympia (no glockenspiel this time, but extra gypsy violin for extra colors) shows Brel getting even more into the spirit of things, with even more different ways to deliver the debilitating blows of au suivant!, au suivant! One might suggest that, with all the theatricality involved, a true live experience with Brel should necessarily involve visuals as well, and, fortunately, we do have footage of at least one performance from his prime, where the body language adds a lot to the message as the man keeps effortlessly switching between the guises of the tormented and the tormentors, in a display of split personality that eventually descends into near-complete madness. I especially like the evil grin on Jacques’ face at the very beginning of the video, as he pinpoints some unfortunate soul in the audience — a not-so-subtle hint that the song is as much written about all of us (well, all of us with a certain degree of self-awareness, I’d say) as it is about himself. After all, one way or another, all of us eventually have to stand in line to lose our innocence to a mobile army brothel prostitute, don’t we? Figuratively speaking. Or, heck, maybe not as figuratively as we’d like to imagine...

In terms of popularity, ‘Au Suivant’ is certainly nowhere near as famous as ‘Ne Me Quitte Pas’ or ‘Amsterdam’ or a couple dozen other Brel classics, but it did have an interesting afterlife in the Anglophone world that merits an investigation. You can still hear the original translated version as sung by Mort Shuman himself on the largely forgotten original cast LP of Jacques Brel Is Alive And Well: the arrangement, following the conception of popularizing Brel «the way he is», is very close to the original, but Mort himself, unfortunately, does not quite have the theatrical flair to deliver all the nuances and dynamics of the song — the ability to craft brilliant melodies of the caliber of ‘Save The Last Dance For Me’ and ‘His Latest Flame’ does not guarantee equal talent in all other spheres of the musical tradition, and it is hardly a coincidence that we usually learn of Mort Shuman through the Drifters and Elvis Presley rather than vice versa.

Far better remembered is the performance of ‘Next’ by Scott Walker, who was probably Brel’s biggest fan (well, after Shuman) in the English-speaking world of the late 1960s and included several of Jacques’ songs on each of his first three albums. Scott Walker was a great artist, and some of his covers are quite outstanding, but I am not sure that ‘Next’ was such a great choice for him, or, conversely, that he was the right artist to sing ‘Next’. The performance is simply too perfect, too «Apollonian» by way of delivery where a Dionysian approach makes far more sense — it’s kind of a dirty song, after all, while Walker delivers it like an engraved vision of Lord Byron. I sort of get the tragedy in this performance, but I don’t get any real human pain from it.

As far as I’m concerned, the true, and only, way to get the proper vibe out of an English rendition of ‘Au Suivant’ is the Alex Harvey way — either by way of the studio version, recorded by The Sensational Alex Harvey Band for their second album (appropriately called Next... itself), or the chilling live version recorded for the Old Grey Whistle Test about a year later. Unfortunately, Harvey never covered any other Brel songs, but he was, perhaps, one of the most «Brelian» characters on the Anglophone music scene — far more so than either Scott Walker or David Bowie: a genuinely tormented soul, torn between intelligence and madness, depth and gimmickry, lowliness and idealism. Even if he is armed with Blau and Shuman’s translation rather than the original, he sings each line of the song as if he were truly living it, and he fully embraces the idea — as we have established, already inherent in the subtle changes of the translation — of taking the song to the utmost heights of anger and depths of madness (as with Brel himself, the live version seriously raises the stakes over the studio one).

I have seen occasional quibbles — usually from the «I’m the only one to tell you plebs that nothing beats the original» mentality people — about how Harvey’s interpretation distorts or trivializes or «ham-fistifies» Brel’s attitude, but the truth is that both Brel and Harvey are very much being themselves while using the song as a vehicle, each in their own way, similar, but different. Where Brel plays a traumatized, deeply hurt character whose self-psycho-analysis eventually opens up a small window to a brighter future (his terrifying lyrics of future self-immolation are really not to be taken literally), Harvey sings the song like a doomed man — nay, like a fallen one, with no hope of salvation whatsoever, for whom the only remaining consolation is to revel in his own ugliness and misery: the eerie grinning smile of mime-painted Zal Cleminson on guitar is really his own Joker-ish evil clown reflection. You sort of expect the guy to end the song by dropping an atomic bomb over London or something — and we’d probably exonerate him for the deed, because it is so transparently clear that society made him. Brel finishes the song on an almost triumphant note, irony or no irony; Harvey’s "NOT EVER TO BE NEXT!..." reverberates around the room like the last scream of a condemned sinner falling into a bottomless pit of hellfire. It is he who brings the Wozzeck-like overtones of the song to their utmost logical conclusion.

Other people have had their versions of the song, too, both in French and in English (Gavin Friday) or even with a new, more literal but poetically inferior English translation (Marc Almond), yet none of these even begin to approach the expressivity of Brel’s original or Harvey’s cover — for various technical reasons, each specific to a certain version, plus a single general one: all of these other people take the song as theater, not as an inalienable part of their inner selves. Brel, for all the nods to theatric tradition in his recordings and stage shows, did not really do theater — and neither did Alex Harvey, a kindred soul to the Belgian artist if there ever was one; heck, I just realized that Brel died at 49 from cancer and Alex at 47 from a heart attack — and somehow both of these deaths feel almost expected of them. In some way, they burned themselves down for our sake, too — the best way we can repay them is, well, maybe try and promise never to be next, whatever it may take?...

Love to see it!

Not a real Brel knower, but I have heard all the albums and love a great many songs. My French is good enough to understand, especially when reading, but not good enough to really appreciate 'in real time'. But as you say, the music and performance is (usually) good enough anyway to get it.

Songs like J'arrive or Amsterdam (live '64) are genuinely frightening (and electrifying) experiences, the likes of which I don't know of from the rock/pop world. Other favourites are Quand on n'a que l'amour, J'en appelle (that sweep!), Ces gens-là, Mon père disait, Jaurès of the last album... well a great many really, now that I'm looking over the whole track lists.

This one was never actually one of my favourites. I think I'm more partial to the French than the German tradition, as you outline them. And anyway, though this need not hinder appreciation, I actually don't recognise or share in the sentiments (guess I'm too comfortably conformist). But I do recognise the artistry.

Haha, this was out of the blue, wasn't expecting a little detour to Brel -- much less to a song i've somehow never heard, or simply not remembered. I was a moderate fan of his for years after seeing his live version of "Ne Me Quitte Pas", and then more wide-open musical songs like Valse à Mille Temps. As you say, very Brechtian, love the version by Alex Harvey & his band. Léo Férré did this sort of thing rather well too (e.g. C'est l'Homme), and both of them presumably influenced Serge Gainsbourg years later. Thanks for going down this little (aposite) Easter rabbit hole!