Tracks: 1) Oh My Babe; 2) Ring-A-Ding Bird; 3) Tinker's Blues; 4) Anti Apartheid; 5) The Wheel; 6) A Man I'd Rather Be; 7) My Lover; 8) It Don't Bother Me; 9) Harvest Your Thoughts Of Love; 10) Lucky Thirteen; 11) As The Day Grows Longer Now; 12) So Long (Been On The Road So Long); 13) Want My Daddy Now; 14) 900 Miles.

REVIEW

"You take my name / And hang it high / You paint my picture / With colored lies / But it don’t bother me / What you do".

Thus go the words to the title track on Bert Jansch’s second LP, and I immediately have a problem with that — if he were singing about somebody else (like, say, an allegorical projection of Bob Dylan), it would make sense, but the natural instinct is to assume that he is singing about himself, and if so, that’s a bit of an inadequate attitude to assume — Bert’s popularity never even began to approach the average level of the average pop star, and it is difficult for me to imagine anybody at the time who’d be paid well enough to paint a picture of Bert Jansch with colored lies. I have a sneaky suspicion that Bert would not be opposed to somebody painting his picture with colored lies, just so that he could write a song about it and dashingly shoot down the infidel. But I also have another sneaky suspicion that he might never have found an actual target, so he ended up imagining one and then gleefully sending out his barbed arrows. (I may be wrong, though. If you ever happen to come across a painting of Bert Jansch, canvas, colored lies, 20 x 20 inch hanging in some obscure gallery, please remember to convey to me the artist’s exact signature).

If that introduction comes across as a little mean, blame it on a light revenge wish which I feel like I’ve earned the right to after three listens to Bert’s sophomore... well, not exactly slump, but perhaps stutter or stumble would be a better term here. The problem, I think, was in the man’s instinctive mistrust of everything associated with the record industry. His self-titled debut, if you recall, was basically recorded «at home», in a setting that seemed comfy enough for Bert; but after it went on to sell a surprisingly high number of copies for such a low-key «indie» project, Transatlantic arranged for the next sessions to be held at a proper recording studio — the famous Pye Studios, to be exact — and Bert allegedly hated it, making sure to arrive there on one particular day in April, record everything in about three hours, and then get out. (At least this is how he tells the story himself; not sure if it’s entirely true or if the real sessions took longer than he remembers it).

In any case, it does very much sound as if all these fourteen new songs were recorded in three hours’ time — in fact, most of them might have easily been written in three hours’ time, if you ask me. For all my reservations about Bert Jansch, that record did establish Bert as one of the finest and most imaginative acoustic guitar players of his generation; the melodies daringly mixed folk, blues, jazz, and Eastern influences in ways the average Greenwich Village bard would hardly even begin thinking of. But here, almost everything rests either on the medievalistic drone pattern, such as you hear in the opening number ‘Oh My Babe’ — or, more commonly, on the cross-picking style, such as you hear in the second song, ‘Ring-a-Ding Bird’, and then... in many others on this record. If you suddenly get a weird feeling that half the songs here sound like John Lennon’s ‘Julia’, well, you know how it goes: Donovan got this from Bert Jansch, Lennon got this from Donovan, but ‘Julia’ is still a better song than all of the tunes on this record put together. Life’s cruel.

Anyway, perhaps it don’t bother Bert at all that all of his songs here sound the same, and perhaps — who knows — he was even going on a bit of a fuck-you vibe here, just improvising stuff on the spot to fulfill a contractual obligation, but the fact remains that It Don’t Bother Me never had any impact comparable to its predecessor, and I do believe that the title track is pretty much the only one that occasionally crops up on his best-of compilations, probably because (a) well, it’s the title track, it’s got privilege and (b) its arrogant, pretentious lyrics give the impression of a mighty ponderous personal mission statement, so it’s thought of as something that should, by definition, be part of any introduction to the man. But come on now, ‘It Don’t Bother Me’ is just not a very good song. As is expected, Bert’s problems with lyrics continue to plague him — "what truth is told / of who I am / shall break the silence / of waters calm" is both clichéd and ungrammatical — and it’s all based on the same cross-picking pattern we have already heard on three or four songs before it. In all honesty, it’s almost self-parodic — the first authentic look at the «shy reclusive indie songwriter hates the limelight» stereotype where your natural reaction might be «buddy, if you hate the suits that much, just stay at home, nobody had to drag you all the way to Pye Studios on a leash». Then again, what the heck do I know — maybe they did get him there on a leash, and this was just an instinctive reaction. But it still doesn’t count as genius.

Another song that is always quoted in any review of this LP is ‘Anti Apartheid’, continuing the series of political songs that Bert already introduced previously and now moving on to South Africa (or to just about anywhere, because the lyrics make no other direct references specifically to South Africa and could simply be construed as a general anti-racist statement). The sentiment is noble, but the lyrics are predictably clumsy, and the melody is the same as ‘It Don’t Bother Me’, only in a different key. I do, however, spot subtle similarities between ‘Anti Apartheid’ and Lennon’s ‘Working Class Hero’, at least in structural terms — both songs are acoustic ballads offering acute social critique, based on a bluesy three-line rhyming sequence plus a one-line chorus resolution, so I’m pretty sure Bert could be at least a subconscious influence on John here as well. Problem is, not only was John a better singer, but he could also wring more tragedy out of his technically limited chord sequences than Bert does from his; ‘Working Class Hero’ succeeds in earning my empathy through its sound alone, while ‘Anti Apartheid’ just sounds pretty (from an instrumental perspective) or hollow (from a vocal point of view).

Now, before this gets uglier than necessary, let me try and concentrate on the outstanding stuff. First, consistent with what I already said about the debut, the short instrumental tracks are almost always tastier than the vocal ones. ‘Tinker’s Blues’ may not be a big departure from the picking pattern of the preceding ‘Ring-a-Ding Bird’, but the lack of vocals allows Bert to focus on making the chord sequence a little more complex and a little more stable, reviving that old John Fahey quasi-Zen vibe of «sitting by the riverside, watching the world roll by», and there’s a kind of honesty and humility in this that you won’t really find in any of the album’s vocal hymns.

Then, coming right after ‘Anti Apartheid’, ‘The Wheel’ is literally it — an attempt to make an acoustic depiction of a set of wheels plodding along in their cozy rut, occasionally hitting upon some light additional obstacle. It’s incredibly complex from a technical standpoint (if you watch a video of Bert playing it live on some Norwegian TV show from 1973, you won’t even notice how he manages to get in those additional lead lines on the bottom strings), but since the tune has an actual purpose beyond merely showing off, getting amazed at Bert’s technique will probably come after getting impressed by the vividness of the musical depiction, which is precisely how things should run when music is done right, not wrong. I don’t think that Bert here is rewriting any rules of the game set by previous masters of acoustic folk guitar — but he presents himself as one of the top players, without shouting about it. Ironically, ‘The Wheel’ is about the exact same length as Van Halen’s ‘Eruption’, features a comparable (if not superior) level of technical accomplishment, makes a classier and more tasteful statement (don’t get me wrong, though, I do enjoy ‘Eruption’ quite a bit, in a cheesy sort of way), and, on a certain level, is just as theatrical — but then again, you know, most people do flock together to marvel at the horrifying exclusive beauty of an erupting volcano rather than sit on their porch and marvel at the wonder of spokes or tires set in uniform motion by physical forces beyond our comprehension, so it’s not that difficult to understand why ‘Eruption’ sells and ‘The Wheel’ does not. For much the same reasons, I’d say, that we pay constant attention to airplane crashes, but remain unperturbed by the much higher number of people dying in automobile accidents every day...

...anyway, enough digressing. The third instrumental on the album, ‘Lucky Thirteen’, is interesting in that it is an actual duet between Bert and John Renbourn, his musical partner since 1963, an accomplished acoustic player in his own right and the future co-founder of The Pentangle, along with Bert. Starting out solo, Bert is soon joined by Renbourn, and the two start weaving in and out of each other’s melodies in their trademark «folk baroque» style — actually, the wordless song is about 1/3 folk, 1/3 blues, and 1/3 jazz, I’d say, and the guitar melodies are somewhat reminiscent of the contemporary Byrds sound — for some reason, my mind immediately went to the officially unreleased instrumental drone of Crosby’s ‘Stranger In A Strange Land’, though it could not be influenced by ‘Lucky Thirteen’ for chronological reasons. Actually, I know the reason: both songs employ a similar type of plodding, «travel-on» progression, against which other things are happening, as if you were making your way through some thick, busy, lively, and mysterious jungle. Jansch and Renbourn get this anything-can-happen-to-you idea buzzing on, far more evocative and exciting, I’d say, than the majority of tossed-off vocal tunes on the rest of the LP.

Of said vocal tunes, I’d probably have to single out ‘My Lover’, which may be one of Bert’s most impressive combinations of Western and Eastern melodic power — the rhythm churns out a busy Celtic pattern, while the lead is unmistakably Indian in tone. Actually, there are three different guitar parts here: in addition to Renbourn playing the sitar-like lead, there’s also Roy Harper with additional bits, making the track into a one-of-a-kind acoustic trio. The only bad thing about it is... yes, well, of course you guessed: the lyrics and the singing, with Bert’s whiny-nasal "my lover, my lover" refrain not producing the right romantic impression. (Pretty sure it must all have been a big influence on The Incredible String Band, though). "A queen dressed in lace / Like winter’s falling snow / You are dancing with my dreams / You sing of broken time" — that’s the kind of lyrical content that ChatGPT usually writes for you these days. You can keep the lace, the falling snow, and the bad vocals, and just leave me the wonderful instrumental backing — I’m not saying the vocal part is exactly alien to the experience, but I’m getting a «Yoko Ono slips into the studio for the final touch» vibe here, and that surely can’t be good.

Brushing aside some more of those short, inconsequential, and vocally unattractive ditties like ‘A Man I’d Rather Be’ (Bert’s attempt at folksy humor — but he’s no Bob Dylan when it comes to that) or ‘Want My Daddy Now’ (Bert’s attempt at putting himself in the place of a little girl who misses her daddy gone away to war — I appreciate the sentiment, but don’t we have Joan Baez for that kind of thing?), and briefly mentioning in passing the nod to fellow Scotsman Alex Campbell, whose ‘Been On The Road So Long’ is getting covered here, we’ll stop at the traditional ‘900 Miles’, closing out the album, for which Bert hauls out the banjo, but still plays it largely as if it were one of his guitars, and in a decidedly non-American way for an instrument most associated with bluegrass aesthetics. It feels a little weird, as if he’d decided to intentionally finish things off on a dirtier, broken-up mood, rather than with something particularly flashy-professional. Almost like a little punkish nod to the listener before the album gets shoved back inside its sleeve.

And there you have it — fourteen tracks of uneven quality, alternating between predictable and unpredictable, beautiful and ugly, unique instrumental techniques and awfully written lyrics. But even if, on some objective level, It Don’t Bother Me was clearly a marking-time toss-off, Bert Jansch always has two redeeming qualities about him: his fingers have a touch of genius, and his hard-working ethics makes (or at least should make) you respect him as a professional even when he’s coasting or when he’s posing as some sort of Tim Buckley’s elder brother. Besides, it clearly don’t bother him what I see, what I do, or what I say, so let’s just end this right here and now before I really start twisting his words like plaited reeds to mark my gain and help my needs. Oh, if only twisting those words just a little bit could really help my needs!... but that’s just wishful thinking, both on my part and Mr. Jansch’s.

Only Solitaire reviews: Bert Jansch

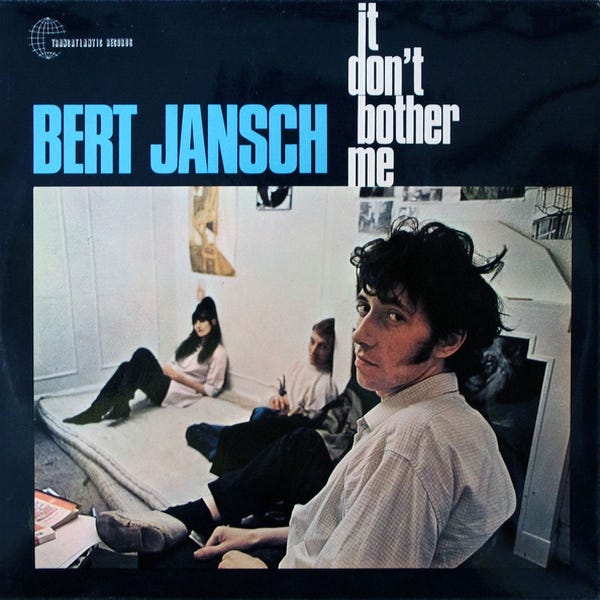

I like the album cover, though 🤔

Maybe she hung his name high like she hanged it on a tree, for everyone to see how miserable it is. And painted with some kind of shit, too. After all, this is what ladies usually do. Agrees with the 1st verse then, too.