Tracks: 1) Gunslinger; 2) Ride On Josephine; 3) Doing The Craw-Daddy; 4) Cadillac; 5) Somewhere; 6) Cheyenne; 7) Sixteen Tons; 8) Whoa Mule (Shine); 9) No More Lovin’; 10) Diddling; 11*) Working Man; 12*) Do What I Say; 13*) Prisoner Of Love; 14*) Googlia Moo; 15*) Better Watch Yourself.

REVIEW

You certainly gotta give Bo some credit for closing out 1960 with a third LP of mostly «original» material (the quotation marks are important, though) — even if the ten tracks on the original LP barely amount to 25 minutes; no pop artist from the same era was capable of matching such an achievement. It is almost as if some sixth sense took over, insinuating that Bo Diddley’s grand mission in 1960 was to save rock’n’roll from extinction and that, in order to do that, he had to work thrice as hard as he used to — to make up both for himself and for all those rockers who’d died, crashed, burned out, or mellowed out in the great catastrophe of 1959-60. Unfortunately, this was exactly what it was: work. The same crisis that affected all of those Bo Diddley’s peers that he was stepping in for affected Bo just as well — and Bo Diddley Is A Gunslinger is a perfect example of this, a record that features plenty of well-crafted invention but almost zero inspiration.

In retrospect, the record does have a rather surprisingly high reputation, with many critics and fans alike referring to it with what seems to me like somewhat inadequate warmth and affection. It sometimes finds its way onto lists of best albums from 1960 or the early 1960s in general, is often praised for the diversity and energy of its tracks, and quite a few of the songs would later get covered by UK artists (for that matter, the LP itself originally charted as high as #20 in the UK, which was an absolute record for Bo at the time). This singling-out feels weird to me, because essentially, Bo Diddley Is A Gunslinger shares exactly the same flaws and virtues as any other Bo Diddley LP from around the same time — except that it does not contain even a single truly outstanding number of the ‘Road Runner’ variety.

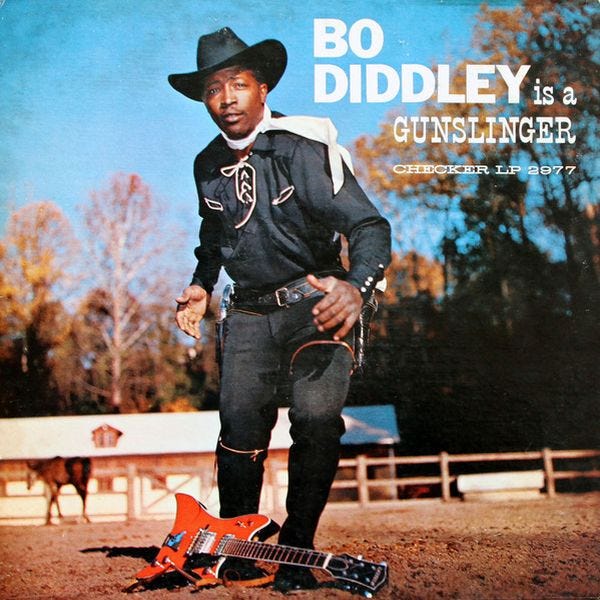

It is possible that some of this mild admiration is triggered by the album’s funny and slightly daring concept. Expanding upon the theme that he initiated with ‘Walkin’ and Talkin’ on his previous LP, Bo makes this one into a «semi-conceptual» record, a part of which revolves around classic Western themes — only a small part, mind you, but enough to pique our curiosity about such a quintessentially African-American performer as Bo Diddley encroaching upon such a quintessentially white artistic genre as the Western. Whoever heard about a black gunslinger back in 1960, anyway? (Not that there weren’t any — history has preserved quite a few interesting examples for us, from Bass Reeves to Isam Dart — but clearly, whatever you can scrape up will still always be the exception rather than the rule).

In theory, this does sound like a promising idea — cross the Bo Diddley beat with all sorts of country-western themes — and it could have aligned well with the agenda of other black artists, such as Ray Charles laying his own claim to the Great American Songbook and the folk / country traditions of white rural America. In practice, however, the concept essentially remains limited to the album cover (but who dropped that guitar on the poor gunslinger’s crushed foot?) and no more than three songs: title track, ‘Cheyenne’, and ‘Whoa Mule’. Of these, ‘Gun Slinger’ is little more than yet another variation on the ‘Bo Diddley’ groove, with appropriately «Western-ized» lyrics ("When Bo Diddley come to town / The streets get empty and the sun go down") and a fairly standard and predictable amount of grooving energy on the band’s part — no less and no more than usual. There’s not even any traces of guitar solos or any special sonic pyrotechnics: just a basic groove stretched out over two minutes. The only idea is that we are supposed to go crazy over the idea that "Bo Diddley’s a gunslinger", but since we know all too well that he really is not, the fantasy ends up in the mediocre tier.

It gets even more baffling with ‘Cheyenne’, an unfinished and unfunny cowboy story which once again draws its musical and lyrical «inspiration» from the Coasters’ ‘Along Came Jones’, this time fully ripping off the verse melody and the "and then?..." bridge. The lyrics are precisely the kind of thing that emerges when somebody without the talent of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller is motivated by jealousy to write something in the style of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, and the music is... well, honestly, I’d simply much prefer a direct cover of ‘Along Came Jones’, just to see what Bo Diddley could do with it, rather than this crude and clumsy re-write. The best thing about the song is its oddly psychedelic extra percussion layer — I have no idea if it’s someone fiddling around with marimbas or using some sort of prepared electric piano, but it’s a cool sonic addition, unfortunately wasted on this complete turkey of a song.

Completing this «Western trilogy» is ‘Whoa Mule (Shine)’, perhaps the most musically interesting number of the three, though this ain’t saying much: essentially a cross between a classic, slightly sped-up, doo-wop chord sequence, a classic Bo Diddley tell-tale verse, and a chorus that adapts a classic country-western cliché to the realities of a new age of music. The «story» is predictably unfunny and its moral is left hanging high up in the air (we had a mule, I liked the mule, the mule liked me, the mule wrecked our wagon, papa tried to shoot the mule, the mule ran away — END OF STORY!), and the music reveals all its secrets in the first five seconds. But, uh, whatever rocks your saddle, Mr. Gunslinger.

Okay, so you’d think maybe Bo was just so enamoured of this new invented personality of his, he thought that the very idea of «Bo Diddley going West» would be enough to redeem any track on which it was promulgated. But the problem is that the «non-Western» songs on the album usually do not fare any better. Thus, ‘Ride On Josephine’, which I have many times seen lauded as a highlight, is essentially a hybridization of Chuck Berry’s ‘Thirty Days’ (chorus) with ‘Maybellene’ (verse, and I don’t mean just the melody — Bo more or less nicked the storyline as well). So what? — people might ask; ethical moments aside (such as not giving Chuck any songwriting credits), what’s wrong with Bo Diddley covering not one, but two Chuck Berry classics at the same time? What’s wrong — or, maybe, not wrong, but simply disappointing — is that Bo slows down the original tempo, deletes the original solos, replaces the original funny lyrics with crude, meaningless simulations, and basically does not produce a single musical argument about why I should ever bother listening to these inferior shadows of far more exciting originals.

Ironically, when he does offer credit (just once on the entire album!), the results are even worse. ‘Sixteen Tons’, that Merle Travis / Tennessee Ernie Ford classic about the grueling hardships of a coal miner’s life, appears on the album in an utterly reinvented and utterly ruined version — sped up and set to a typical Bo Diddley groove, the song becomes an upbeat dance number, completely dumping the original’s gloomy, agonizing atmosphere. To salvage at least a little something, Bo sings most of the lyrics with clenched teeth and a deep growl, as if this were a song of revolution rather than one of resignation. Needless to say, it doesn’t work and only makes things worse. You couldn’t fuck up more if you re-arranged ‘Eleanor Rigby’ as a happy polka dance number.

And I have not even mentioned the worst offender yet: ‘Doing The Crawdaddy’, a sort of thematic sequel to last album’s ‘Craw-Dad’, only this time the added gimmick is a nagging pseudo-children’s choir, chanting the song’s title in the most obnoxious and irritating sort of way over and over while Daddy Bo is providing his «kids» with the proper instructions to master this brand new dance. Do you enjoy hearing the likes of "na-na-na-na-NAAA-nah!" for three minutes? Then this song is for you, especially because there doesn’t seem to be much of anything else to it.

In the end, there are just two tracks on here that I might be willing to single out and salvage for eternity. One is ‘Cadillac’, another lightweight joke number distinguished by a sharper, crunchier, juicier guitar tone than almost anything else on here and some great sax work from Gene Barge. No more original than any other Bo Diddley-beat number, it is at least an example of a formula working well — not nearly as repetitive as ‘Gun Slinger’, featuring better use of the backing vocals than ‘Crawdaddy’ (the call-and-response between Bo’s lines and "C-A-D-I-L-L-A-C" is an aurally pleasing groove in comparison), and with a quirky, satisfying chorus resolution to the verses. At the very least, this song has some fun potential, something that The Kinks would perceive when they recorded a sped-up, slightly «poppified» version of it for their 1964 self-titled debut (replacing saxophone with harmonica).

The other okay number is the final instrumental ‘Diddling’, which, incidentally, is also based on the interplay between Bo’s stormy guitar playing and Gene Barge’s saxophone parts. The two occasionally merge in a wonderful wall-of-sound, predating the future heights of excitement to which raunchy electric guitar and sax duets would soon be taken by garage bands like The Sonics; not sure if there are any compositional advances here, but the saxophone is precisely the ingredient that was needed to update and reinvigorate the Bo Diddley groove. Too bad it remained so drastically underused on all the other tracks.

Subsequent CD reissues of the album threw on from two to five extra bonus tracks, recorded during the same sessions and, rather predictably, suffering from the same issues — thus, ‘Do What I Say’ is another variation on ‘Diddley Daddy’, ‘Googlia Moo’ is another variation on ‘Diddy Wah Diddy’, and ‘Better Watch Yourself’ is another variation on the ‘I’m A Man’ / ‘Manish Boy’ groove. The oddest and most outstanding bonus track is Bo’s take on the old popular song ‘Prisoner Of Love’, which he rearranges as some sort of a cross between a typical Bo Diddley number and a soulful Mexican ballad, ending up with a weird hybrid sound — unfortunately, the song still remains a «novelty».

In conclusion, I might be a little harsh on the album here (I actually gave it a positive review back in 2012!), but I think the best compliment that I could give it at the moment is that Bo himself feels perfectly happy doing it — I think he himself must have been seriously convinced that he was really doing something cool here, rather than merely rearranging old ideas in a new order. The grooves are as tight as usual, the voice is as youthful and energetic as usual, the arrangements are truer to the rock’n’roll idiom than just about any album released in 1960 — what’s not to like? At this point, it may really have seemed as if Bo Diddley was the only classic rocker from the 1950s to escape the 1959-60 stylistic grinder relatively unscathed — sure, out of new musical ideas (replacing them with baffling lyrical and image-related concepts), but keeping the flame largely intact, in comparison with most of his old competitors.

The bottomline is that for the standards of late 1960, Bo Diddley Is A Gunslinger served its mission fairly well, and it did offer the small group of «rock’n’roll survivors», as well as the starving kids over across the Atlantic, a tiny ray of hope that things weren’t nearly quite as «over» with the rock’n’roll revolution as the almighty Establishment would want the world to believe. For the standards of rock music as a whole, though, the album is an almost pathetically mediocre offering. It is quite telling that not a single track off it is typically featured on Chess’ single-disc best-of compilations of the artist, and equally telling that, apart from The Kinks with ‘Cadillac’ and a few latecomers (like George Thorogood, who did a totally rearranged hard rock cover of ‘Ride On Josephine’ in the 1970s), pretty much nobody ever cared about covering these songs — not even such hardcore Bo Diddley fans as The Animals.

Only Solitaire reviews: Bo Diddley

I enjoy Zevon’s live cover of Gunslinger, too. Brings some knife-edge passion into it, whether the song deserves it or not.

Minor note:

"and quite a few of the songs would later get covered by UK artists"

later

"and equally telling that ... pretty much nobody ever cared about covering these songs"

I know Downliners Sect also did 'Cadillac' (not well), but not many covers from noteworthy artists.

Well Van Morrison recently (2017) did Ride On Josephine (also not well), and I guess he's UK.