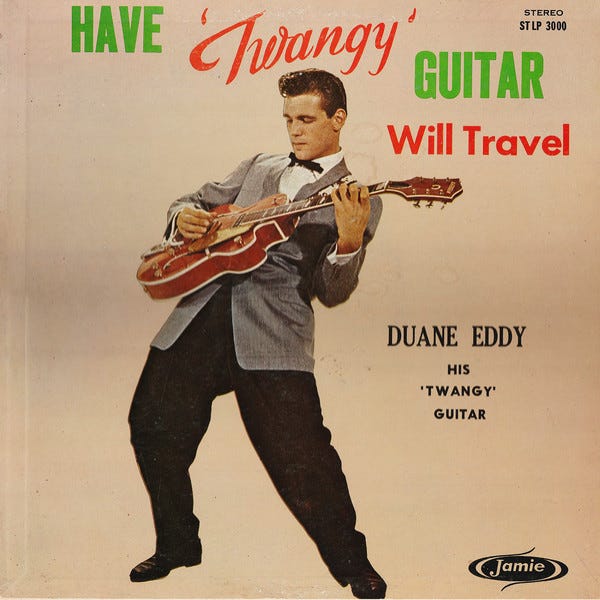

Review: Duane Eddy - Have 'Twangy' Guitar Will Travel (1958)

Tracks: 1) Lonesome Road; 2) I Almost Lost My Mind; 3) Rebel-’Rouser; 4) Three-30-Blues; 5) Cannon Ball; 6) The Lonely One; 7) Detour; 8) Stalkin’; 9) Ram Rod; 10) Anytime; 11) Moovin’ ’n Groovin’; 12) Loving You.

REVIEW

Once again we are reminded that destiny is a fun kind of lady, when going all the way back to the humble beginnings of Duane Eddy’s career — as part of the guitar-vocal duo «Jimmy and Duane», in which he played guitar and sang along with his friend Jimmy Delbridge. Their only single, ‘Soda Fountain Girl’, released in 1955 when Duane was just 17 years old, is a fairly cute teen-country ditty with a mildly startling tempo change in the middle of the tune — and not a single sign of Eddy’s specialness; at this point, he is diligently trying to be Chet Atkins and little else.

Far more important than the single itself was Eddy’s lucky acquaintance with Lee Hazlewood, who had only just started a career as a disc jockey in Arizona, where Eddy was living. Hazlewood was almost ten years older than Eddy, but both of them started their musical career at about the same time (Hazlewood used to be a medical student and then served in the Army during the Korean War), so it is quite natural that when Duane recorded ‘Soda Fountain Girl’ and Lee produced it, neither of the two did a particularly good job. What is nowhere near as natural is that both went on to display remarkable talents — and, for that matter, the role of Hazlewood in shaping the Duane Eddy legend cannot be underestimated; it is essentially comparable to that of George Martin for the Beatles, albeit on a smaller scale, of course.

The innovative instrumental sound that Duane came up with required two ingredients: a special playing technique and clever production. The technique was all Duane’s, as he devised the famous «twangy» way of playing lead melody on the guitar’s bass strings, making them vibrate like a Jew’s harp and achieving a darker, deeper, denser sound without making it feel too aggressive or rebellious. The production was Hazlewood’s, as he compensated for the lack of an echo chamber in Phoenix’s studios by purchasing a huge used-up water tank and installing it as an adequate substitute — this was used for Eddy’s very first single involving the «twangy» technique, ‘Moovin’ ’n Groovin’ (yes, moovin’ with two o’s, as in moo; this is the way the title is spelled on both the original single and the LP, though almost everybody now forgets the second o when talking about the song). Together, they created a tiny bit of magic that would often be successfully imitated, but never truly recaptured in the exact same way.

‘Moovin’ ’n Groovin’ may not have invented surf-rock (at the very least, there were obviously no ideas to associate it with surfing in any way, and the state of Arizona is hardly the best location to come up with surfing-related ideas in the first place), but it did invent and even contextualize a new sound. The opening ringing riff was brazenly stolen by Eddy from Chuck Berry’s ‘Brown Eyed Handsome Man’ — which is all the more ironic considering that Eddy later grumbled about the Beach Boys re-stealing it for ‘Surfing USA’ (a song that, consequently, plunders not one, but two Chuck Berry compositions at the same time). But once the riff has delivered its fanfare, the sound quickly changes to Eddy’s «twang» — the audio equivalent of watching Chuck Berry duckwalk across a hedgerow of distorting mirrors. The low, quasi-grouchy, wobbly, blurring tone of the guitar gives off a strange, proto-psychedelic effect without seriously lowering the fun quotient. Also of note is the equally quirky distorted sax solo from Plas Johnson: Duane liked the saxophone, and would frequently employ sax players (most often, Steve Douglas, who would later play on Pet Sounds and several Dylan albums) to provide nice sonic contrast with all the guitar twang.

Unfortunately, the composition stalled at #72 on the charts, and it was not until the next release that Duane Eddy became a national sensation — although, as is often the case, that next release would be, in my opinion at least, quite inferior to its predecessor. ‘Rebel-’Rouser’, which, according to Eddy himself, was loosely based on a sped-up interpretation of Tennessee Ernie Ford’s ‘Who’s Gonna Shoe Your Pretty Little Feet’, is a melodically trivial country dance number, whose main point of attraction — a «battle» between Eddy’s twang and Gil Bernal’s sax blasts — is utterly minimalistic in nature, and quite repetitive. But maybe because it was faster, and featured overdubbed handclaps and cheer-up vocals from the Sharps (soon to be known as the Rivingtons of ‘Papa-Oom-Mow-Mow’ fame), it did a better job of capturing the public interest, climbing all the way to #6 on the charts and even achieving commercial success across the Atlantic, starting off the UK’s lengthy and loyal romance with Duane Eddy. Maybe this simply means that sometimes less means more; maybe it means that people are downright strange; maybe they did a better job with promotion that time around — or, maybe, all three reasons.

At the very least, Eddy has to be commended for refusing to release the oddly mistitled ‘Mason Dixon Lion’ as the sequel to ‘Rebel-’Rouser’ against Hazlewood’s advice, claiming that the song sounded way too similar to its predecessor. Indeed, each of the next three singles, all of which are included on his first LP, have their own specific features. ‘Ramrod’ (a re-recording of an earlier version credited to «Duane Eddy and his Rock-a-billies» in 1957) is straightforward, insistent rock’n’roll in the vein of people like Eddie Cochran; ‘Cannonball’ is more of a nod in the direction of Bo Diddley, albeit with a rather poppy smoothing out of the Bo Diddley riff and comic yakety-sax thrown in for good measure; and ‘The Lonely One’ is a light-epic country-western ballad, gently nudging you in the direction of the rising sun on the horizon. All three exploit the «twang» style in slightly different ways, and all three are fun, if not particularly earth-shaking.

From a certain point of view, Duane Eddy was a one-trick pony, and he and Hazlewood were never shy about exploiting that pony — many of the singles were directly credited to «Duane Eddy and his ‘twangy’ guitar», and they even inserted the word ‘twangy’ into the title of the LP, despite it breaking the perfect symmetric balance of Have Guitar Will Travel. But it is also worth your while to take a listen to the entire album, which shows that Eddy’s musical preferences extended well beyond what was showcased on the A-sides of his singles. Thus, he was no stranger to slow, soulful blues in the vein of Ray Charles — ‘Stalkin’, the B-side to ‘Rebel-’Rouser’, takes the opening riff of ‘Sinner’s Prayer’ as reference and builds up a deep groove of hysterical distorted saxes, pianos, and gospel background vocals. On the other side of the spectrum, ‘Three-30-Blues’ is more of a regular 12-bar blues-de-luxe, sort of a «B. B. King goes twangy» vibe and, honestly, not at all inferior to whatever B. B. himself was playing at the time. Ivory Joe Hunter’s R&B classic ‘I Almost Lost My Mind’ is given an upbeat pop flavor; and for the sakes of sweet romance, there is a twangy instrumental cover of Elvis’ ‘Loving You’, with Eddy’s low-pitch guitar notes a perfect fit for the King’s deep voice. (In a way, you could probably call that cover the big old grandmother of all surf-pop ballads).

Admittedly, not even the best songs on this album could be said to take my breath away — Duane Eddy had good taste, did not like to repeat himself too much, and invented his own style of playing, but that same style also had him chained and prevented from seriously letting his hair down even when the rambunctious nature of the performed tunes demanded it; besides, his playing technique was limited and he was much better at rigidly churning out repetitive riffs than taking off and going into some less predictable direction — a solid prototype for the Ventures or the Shadows (actually, I think Nokie Edwards would beat him in a creativity competition). But you can still feel the freshness of the playing style even sixty-plus years after the fact — and there is a certain aura of «dark sweetness» to Eddy’s twangy tone which you could hardly get from anybody else. Taken in small dozes, Duane Eddy is fun — and I’d say that a 12-song LP running for less than 30 minutes is precisely the kind of small doze that might endear the guy to you, if you give it a chance.

Only Solitaire: Duane Eddy reviews