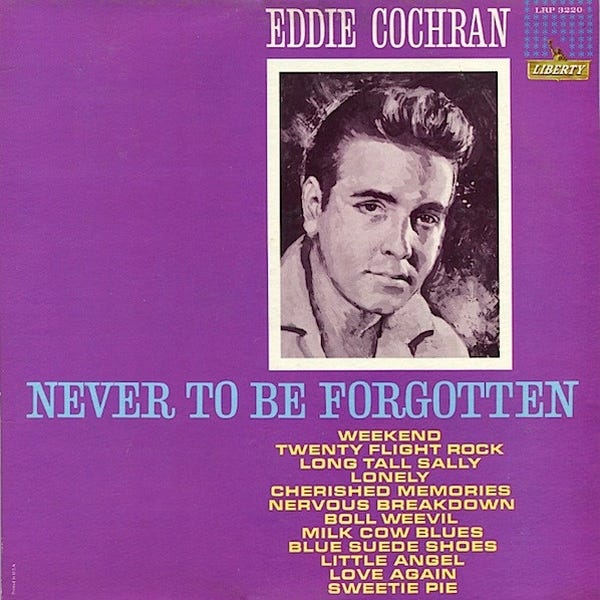

Tracks: 1) Weekend; 2) Long Tall Sally; 3) Lonely; 4) Nervous Breakdown; 5) Cherished Memories; 6) Twenty Flight Rock; 7) Boll Weevil; 8) Little Angel; 9) Milk Cow Blues; 10) Sweetie Pie; 11) Love Again; 12) Blue Suede Shoes.

REVIEW

The second of Cochran’s posthumous albums released on the Liberty label, Never To Be Forgotten is probably also the last of these releases that deserves a special discussion, since, with but two exceptions, it consists almost exclusively of «fresh» material extracted from the vaults; pretty much everything that followed were confusing mish-mashes of alternate mixes, previously released LP-only tracks and B-sides, and a few extra freshly dug-out outtakes. If you are a ferocious completionist, you can hunt for Somethin’ Else!, a gigantic 8-CD box set on Bear Family Records that probably contains every single scrap of recording tape that Eddie left behind, along with an impressive coffee table book that has all the info you ever needed to know about Eddie and more. Unfortunately, I do not have it, so I have no current access to Eddie’s detailed sessionography, and all I know about these tracks is that they were recorded «between 1956 and 1960», which isn’t much (for Eddie, this is the equivalent of a Bob Dylan album said to be recorded «between 1961 and 2024»). But then again, Eddie did not have a particularly dynamic career arc, so I guess exact chronology does not matter that much in this particular case.

The album’s chief asset is, of course, ‘Twenty Flight Rock’ — the song that more or less made Eddie Cochran but, for some reason, ended up left off the 1960 self-titled album, possibly because it was not an official hit single. Never To Be Forgotten corrects that mistake, although in this particular setting ‘Twenty Flight Rock’ all but towers — all of twenty flights — over almost everything else on the LP. While the song is hardly the most angry or aggressive product of the rockabilly era, it is one of its tightest and most tense creations — that frenetic middle section is like Carl Perkins on extra amphetamines, with Eddie playing his solo in a style that ideologically predicts Ten Years After’s Alvin Lee: not particularly inventive or challenging, but driving and engaging series of licks, played as fast as possible for head-spinning effect. But there’s more: surely your senses have suggested to you that there is a serious rhythmic change from the more «wobbly» pattern of the verse to the more straightforward drive of the chorus — this is because (as several people have previously written already) Eddie actually uses a fast habanera-style rhythm for the verse, exchanging it for flat-out boogie in the chorus. (This is even more noticeable, for instance, in this live cover by the Stones from 1981 where it feels like the entire band is drunk off its feet on the verses, only to shake it off for the chorus).

This odd alternation of «stuttering» and «speeding» rhythms, I think, was quite deliberately engineered to match the song’s lyrics — an even odder tale of struggle and defeat that reads like an extension of old broken-elevator-in-skyscraper jokes and could be interpreted any old way, from a lament on man’s fatal dependence on modern technology to an allegory of impotence caused by all of life’s troubles. Ripped out of context, the line "get to the top and I’m too tired to rock" by itself reads like a gypsy fortune teller’s prediction for Elvis Presley (just six months after ‘Heartbreak Hotel’). Put back in context, the whole thing might feel like a lightweight joke — not to be taken seriously at all — but since Cochran’s general vibe was usually all about how «it’s so hard to be a young man in this modern world», I insist on the symbolic significance of the broken elevator. I mean, admittedly, sometimes a broken elevator is just a broken elevator, but this here case ain’t the sometimes I’m talking about. "They’ll find my corpse draped over a rail" might formally be just a joke, but on another plane of existence it’s some pretty dark James Dean-type stuff.

(There is a curious story about the writer’s credits for ‘Twenty Flight Rock’ which, already on the original release, were split between Eddie himself and a certain ‘Ned Fairchild’, who, upon closer inspection, emerges as Nelda Fairchild, an aspiring country-western songwriter associated with the BMI agency. Sources differ on the identity of the primary songwriter, with some evidence pointing toward Nelda — allegedly, she was paid undivided royalties for the song, indicating that Eddie’s name was simply added for the sake of publicity. But I find some cracks in this story: first, the evidence does not really seem to indicate that the royalties were undivided (all it does is certify that Nelda was being paid), and second, it hardly makes any sense for Nelda Fairchild — most of whose other songwriting credits come from rather generic country ballads and jokey Christmas numbers such as Gene Autry’s ‘Freddie, The Little Fir Tree’ — to have written, all by herself, such a risqué, not to mention melodically inventive, number as ‘Twenty Flight Rock’, and then never ever follow it with anything even remotely reminiscent of this style. It seems more likely to me that Fairchild’s songwriting credit was the result of some typical financial scheme of the publishing industry, the exact details of which we shall probably never know; as for the true writer, he/she may have been Eddie himself, or, perhaps, some anonymous genius whose identity shall never be disclosed.)

In any case, the simple fact is that ‘Twenty Flight Rock’ is one of the most outstanding creations in the brief history of classic rockabilly — and this makes it all the harder to gather up comparable excitement for the other songs on Never To Be Forgotten, most of which, needless to say, have been soundly forgotten by everybody except for ardent rockabilly enthusiasts. Not that there’s anything wrong with wanting to hear Eddie’s take on such standards of the genre as ‘Long Tall Sally’ or ‘Blue Suede Shoes’, but his young-man-in-overdrive delivery, so well suited for his original material, does not reveal anything interesting about these songs that Little Richard, Carl Perkins, or Elvis had not yet revealed on their own. And when he tries to put a different spin on Kokomo Arnold’s ‘Milk Cow Blues’ by reverting it back to a slow 12-bar blues crawl (from the rockabillified Elvis version), he comes across as a bit of a clownish parody on classic Chicago blues, mainly because of all the embarrassing vocal exaggeration. (Lesson #1: if you cannot growl, the best decision is to choose not to growl. Applies equally to Eddie Cochran and, say, Ray Davies).

So, naturally, my eye is first and foremost drawn here to fresher songs, credited to Eddie himself in collaboration with Jerry Capeheart, or those written by Sharon Sheeley. The best known one is probably ‘Nervous Breakdown’, later covered by Bobby Fuller and a variety of garage-rock acts — and here, too, the songwriting situation is a bit enigmatic: the song is officially credited to Mario Roccuzzo, a TV actor whose career began in 1960 with a part in The Untouchables and who is absolutely not known for any other contributions to the world of songwriting, singing, or musical performing (in addition, Eddie’s recording is from 1958, when Mario was 18 years old). Furthermore, musically the song sounds exactly like a calculated, formulaic sequel to ‘Summertime Blues’ — recycling the latter’s trademark riff, bass line, and part of its vocal melody. Absolutely the only element through which I could, in my mind, link it to «Mario Roccuzzo» is the slight whiff of an Italian accent with which Eddie delivers the "I’m-a havin’-a... nervous breakdown!" introduction, but that’s hardly sufficient evidence for an entire songwriting credit. My gut feeling is that somebody in the publishing offices screwed up again, deliberately or not — the song is most likely a Cochran/Capeheart original.

A separate mystery about ‘Nervous Breakdown’ is that, as far as I can tell, the song stayed in the vaults until its eventual release on this LP (and only later, in 1963, as an actual single) — yet musically and thematically, it also has very strong connections to ‘Shakin’ All Over’ by Johnny Kidd over in England: the whole "see my hands, how they shiver / see my knees, how they quiver" bit, the stop-and-start structure with the «quivering» hook of "n-n-n-ervous breakdown!...", and even that bass line would largely re-emerge unscathed in ‘Shakin’ All Over’. (And when you think of it, the fact that The Who would later chain-link ‘Summertime Blues’ and ‘Shakin’ All Over’ for their classic live act becomes more than pure random coincidence). My only possible blind guess is that Eddie may have performed the song during his ill-fated first and last tour of the UK (January to April 1960), and that Kidd may have been in the audience at one time to hear it and be influenced by it — but that’s just groping in the dark. The single unassailable truth here is that the two songs are very clearly related. But ‘Shakin’ All Over’ is the better one: it manages to specifically pick out the subtle elements of darkness and insanity present in ‘Nervous Breakdown’, throw out the lightweight playfulness, and tap even deeper into the depths.

The other originals are ‘Boll Weevil Song’, which I already discussed previously, and ‘Sweetie Pie’, an outtake from 1957 with Eddie at his most Gene Vincent-like; the song oozes stereotypical rockabilly simplicity to a proto-Ramonesque degree by featuring the most rudimentary chords and the most laconic lyrics (the writers could not even be bothered to come up with two different verses), but the problem is that Eddie Cochran does not have his own rockabilly overcoat, and when he does not amplify his image with a captivating bit of unique teenage drama, all he does is peddle formula, and I like my formula peddled in a more idiosyncratic manner. Not that it ain’t fun or anything: after all, you gotta admire a man whose only message is "she’s my steady girl, ’cause she’s my sweetie pie" and who is sticking to it through thick and thin.

From the loving writer’s hand of Sharon Sheeley come three more songs, all of them ballads this time: the liveliest of these is ‘Cherished Memories’, a curious hybrid between a doo-wop serenade and a merry military march that I could picture Eddie whistling along with his brother-in-arms on a lively jog from the barracks to the training grounds. Neither doo-wop nor martial tunes are among my favorite musical genres, but at least the novelty nature of their crossing makes the song more memorable than ‘Lonely’ and ‘Love Again’, standard slow ballads that at least deserve a better singer than Cochran, even if his lower range was fairly impressive for a guy who chiefly built his reputation on his mid-to-upper range.

Finally (or rather initially, since it opens the LP), there is ‘Weekend’, an Elvis-type pop song (albeit subtly based on a smoothed-out variation of the Bo Diddley beat) credited to «Bill and Doree Post» — whoever they were, they at least knew a thing or two about what sort of material to submit to a guy like Eddie, as the song, once again, continues the issue of «all we want is have some fun but those nasty grown-ups don’t let us». It’s certainly less socially conscious or musically ass-biting as ‘Summertime Blues’, but it is quite in line with the former — not only are those nasty grown-ups preventing us from finding decent work for good wages, they are doing everything in their power to spoil our party fun as well. Unfortunately, the meek arrangement and especially the irritatingly infantile la-la-la backing vocals push the song toward Jan & Dean territory; I certainly do not see swarms of terrified parents losing sleep over the song in my mind’s eye.

All in all, this is an enjoyable record, even if ‘Twenty Flight Rock’ — and, perhaps, also ‘Nervous Breakdown’ for all of its curious features — are likely the only two songs on it that somewhat justify the title. Even Sharon Sheeley, whose liner notes on the back of the LP ("Eddie’s love will always be my most precious possession") are conventionally touching, would «forget» about Eddie rather quickly, marrying Jimmy O’Neill in 1961 and going on to create the Shindig! show with him. Liberty Records would also continue to diligently gather the dregs from the vaults for years, but it never really gets better than this one LP. And perhaps that’s the way it was always going to be. Of all the heroes of the rockabilly era, Eddie Cochran was arguably the one who flashed his «young man blues» tag more flamboyantly than anybody else in the business — and then was taken away from us once the celestial powers understood that he’d never be fit for much of anything else in this world anyway.

So do not waste time trying to guess whether he would have gone on to something bigger; like most of his peers from the same era of music-making, he would have not — the likeliest alternative to dying would be turning into a nostalgia act, playing ‘Summertime Blues’ at county fairs and «rock’n’roll revivals» for the rest of his life. Yet this sober realization should by no means diminish the power of his best songs, all of which still pack more spirit, intelligence, and authenticity than any random selection of glossy, auto-tuned «rebellious» teen-pop crap from the hit charts of the 21st century — and yes, of course you saw that one coming, but how else am I going to justify these reviews in the face of the new reality?

Only Solitaire Reviews: Eddie Cochran

This nice article served for me to google a bit: The Nervous Breakdown - Shakin' All Over connection is intriguing. Great song by the way, and yeah they're so close. I didn't find a thing about that but at least it served me to discover that Nick Simper, the original Deep Purple bass player was a member of Johnny Kidd and The Pirates. All is connected, or hyperlinked I should say these days.