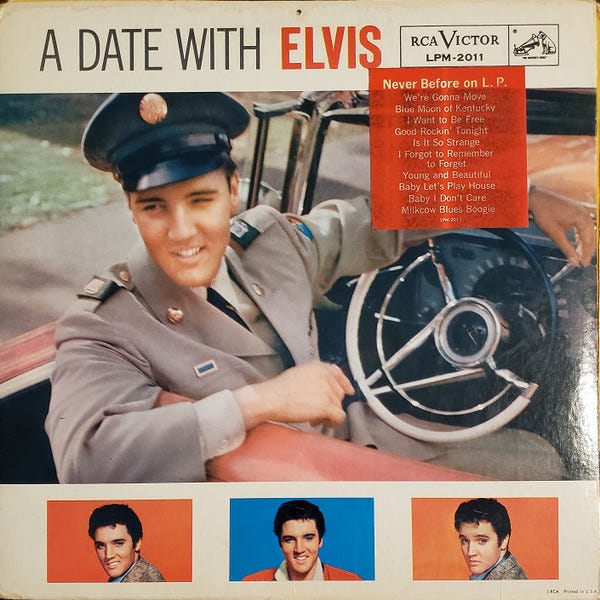

Tracks: 1) Blue Moon Of Kentucky; 2) Young And Beautiful; 3) (You’re So Square) Baby I Don’t Care; 4) Milkcow Blues Boogie; 5) Baby Let’s Play House; 6) Good Rockin’ Tonight; 7) Is It So Strange; 8) We’re Gonna Move; 9) I Want To Be Free; 10) I Forgot To Remember To Forget.

REVIEW

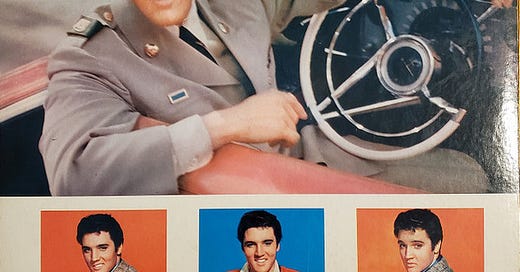

I suppose that if you really wanted to have a date with Elvis in the summer of 1959, youʼd have to go to Germany, sneak inside a U.S. Army base, and be incarcerated as a potential Soviet spy. But if you were willing to settle for the next best thing and save yourself a lot of hassle, RCA Victor Records still had the power to placate you with more stuff from the vaults — five songs on this mini-LP go back to the Sun era, and five more are culled from various later sources. With this push, the Sun backlog was almost exhausted, yet it cannot be said that RCA left the least for last: ʽBlue Moon Of Kentuckyʼ, ʽMilkcow Blues Boogieʼ, ʽBaby Letʼs Play Houseʼ and ʽGood Rockinʼ Tonightʼ are every bit as fabulous as it gets with early Elvis — and the only reason why I am leaving out ʽI Forgot To Remember To Forgetʼ is that it takes things more slowly and sentimentally, being a better fit for fans of country balladry than good old-fashioned rock’n’roll.

And speaking of good old-fashioned rockʼnʼroll, its entire philosophy just might be condensed in that false opening of ʽMilkcow Blues Boogieʼ, which seems to amicably mock the ancient slow blues tradition — that "hold it fellas, that donʼt MOVE me, letʼs get real, real GONE for a change!" bit when Elvis stops the «first take» and directs his bandmates to speed up and rip it up is like an artificial recreation of the celebrated epochal moment of truth during the sessions for ʽThatʼs Alright Mamaʼ — though, I suppose, not that much more artificial than the flag-raising photosession on Iwo Jima: both moves recreated events that were so fresh and recent, they might just as well simply been stretching out the space-time continuum a bit. It is that particular twilight zone where lines between theater and reality get fuzzy.

Anyway, instead of moaning the blues à la Sleepy John Estes, which he could never convincingly do anyway, Elvis turns ʽMilkcow Blues Boogieʼ into the punkiest of all his early tunes — the level of testosterone here would not be outdone until ʽHound Dogʼ — and sets the tone for countless cover versions to follow, from the Kinks to Aerosmith and beyond. Remember that it is really a murderous song, no flinching about it: "get out your little prayer book, get down on your knees and pray", "youʼre gonna be sorry you treated me this way" and the like are delivered by Elvis in much the same way they would be delivered to Desdemona by a modern day Othello, much less courteous and well-spoken than in Shakespearian times and much more prone to quick action — and although Elvis is inheriting, rather than inventing, that tradition, his gruff, lead-heavy vocal performance raises the stakes considerably, as the man clearly revels in this play with fire. This is the kind of material that makes it easy to understand the «danger» that American parents perceived in the young fellow — and you donʼt even have to watch any hip-swiveling to feel it in your bones sixty years on.

The same applies to ʽBaby Letʼs Play Houseʼ — let us not completely forget Arthur Gunterʼs fun-filled original, but with the increased tempo, the trembling-rumbling echoey bass drive, and the hiccupy we-want-it-and-we-want-it-now vocal performance, Elvis fully appropriates the song: not so much for specifically white audiences as, much more importantly, for young audiences, getting this stuff out in the open air despite its originally being reserved for relatively reclusive and generally «mature» listeners. (Sometimes we need to be reminded that before these Sun sessions, roughly speaking, music specifically targeted for the young did not even exist, much like childrenʼs literature did not exist before the likes of Lewis Carroll and Frank Baum). Furthermore, it is one thing to issue an invitation to «play house» if you are past the age of 30, but the effect of such an invitation on the mind of a hormonally-troubled teenager in 1955 could certainly be compared with the effect of ‘Darling Nikki’ on Karenna Gore thirty years later. The only saving grace is that, most likely, 90% of parents and kids alike did not have a good understanding of what «play house» actually meant. (Now only imagine if Gunter, and Elvis after him, would save everybody some linguistic trouble and straightforwardly name the song ‘Baby Let’s Live Out Of Wedlock’ instead!).

In a similar way, Elvis took Wynonie Harrisʼ jump-blues classic ʽGood Rockinʼ Tonightʼ, sped it up, delivered it from its «respectable» saxophone-heavy arrangement, replacing the sax with stinging, scorching, but strictly disciplined Scotty Moore guitar licks, and turned it from a nightclub standard into a school ball anthem, omitting all of the songʼs dated lyrical references to imaginary characters like Sweet Lorraine and adding the "weʼre gonna rock, weʼre gonna rock" bridge for emphasis. That Scotty Moore solo, by the way, is one of my personal favorites: unlike many others, which Moore probably just made up on the spot from a (sometimes genially, sometimes not) randomized selection of stock country licks, this one is pre-meditated, simple, geometrically exquisite, perfectly shaped and making great use of microtones, a classic example of emotionally charged sonic greatness made with very limited means — in some ways, still unsurpassed to this very day.

The earliest of all of these is ‘Blue Moon Of Kentucky’, the original B-side to ‘That’s All Right Mama’ — and just as symbolic for the future as the latter. In a way, that first single could be construed as a powerful claim to racial equality in the face of rock’n’roll: ‘That’s All Right Mama’ put the classic black spirit in the new automobile of rockabilly, whereas ‘Blue Moon Of Kentucky’ did precisely the same for the classic white spirit, turning Bill Monroe’s bluegrass standard into something the Blue Grass Boys could never have foreseen coming back in 1945. (After Elvis’ version came out, Monroe would rearrange the song so as to do the first half in the old-fashioned waltzy way, and the second half in the new-fashioned boogie way — not even an old codger like that could withstand the power of true rock’n’roll!).

No wonder that next to these early, ground-breaking, exciting Sun classics all that later RCA material pales a bit, especially after Elvis went really heavy on the doo-wop ballads. On the album, new material is carefully intertwined with the old shit, but it is impossible not to note the difference — cleaner, brighter production and richer arrangements at the expense of raw rock’n’roll energy and minimalist, in-yer-face youthful aggression. Additionally, the odds cannot help but be stacked in favor of Sun-era singles simply because most of the RCA-era stuff is pulled off from the lesser tracks on previously released EPs such as Jailhouse Rock and Love Me Tender. You put ‘Milkcow Blues Boogie’ up against ‘Hound Dog’ or ‘Jailhouse Rock’ and you can have yourself a debate; put it up against ‘We’re Gonna Move’ and the case is closed.

Anyway, since I have already briefly touched upon most of those songs in previous reviews, let’s not talk about them any more and, instead, once again use this opportunity to discuss the last couple of singles that were released during Elvisʼ army stint, stemming from the same 1958 Nashville session that yielded ‘One Night’ and ‘I Got Stung’. Of these, ʽI Need Your Love Tonightʼ is a fun, catchy, hard-driving pop-rock tune brimming with nothing but positive energy — yet, like most of the great rockers, Elvis is always at his best when a bit of devilishness is thrown into the pot, so the real kicker of 1959, and one of my favorite Elvis recordings of all time, was ʽA Big Hunk Oʼ Loveʼ, notable not only for its ultra-tightness and humor, but also for giving a great chance to Floyd Cramer and Hank Garland, two major architects of the classic Nashville sound, to shine respectively on piano and lead guitar. (Originally, I was all but devastated to learn that it was not our man Scotty to play the six-string on this track, but give Hank plenty of credit for deceiving me by incorporating some of Scottyʼs guitar-whipping aesthetics into his own style here for consistency.)

I think what gets me most about ‘A Big Hunk O’ Love’ is that it literally feels like the tighest wound-up spring in Elvis’ entire career — the whole song, with its unceasing flurry of quarter-notes from all the instruments, is delivered on one breath, while managing to avoid the impression of «cacophonic messiness» into which the band accidentally plunged with the production of ‘I Got Stung’ (also a great and sonically unique recording, but a tad crazier than the acceptable requirements for pure rock’n’roll fun). Within this context, Elvis, Floyd, and Hank form a three-headed monster, each of whose heads is a hyperactive equivalent to Jim Carrey on amphetamines — vocals, piano, and guitar flow in and out of each other without giving you a chance to catch your breath, and none of the three parts cracks or stutters even once. I cannot even begin to imagine what sort of combination of professionalism and inspiration is needed to produce that sort of level of collective rock’n’roll tightness; the closest analogy in my brain would probably be the Clash’s version of ‘Brand New Cadillac’ from London Calling, and it is also quite telling that not a single live version of either of the two songs I have ever heard (Elvis would later incorporate ‘Hunk’ into his regular set on his post-«comeback» tours) came anywhere close to matching the aggressive tightness of the studio takes — such unique events simply cannot be replicated.

Thus, with the release of ‘A Big Hunk O’ Love’, «Fiftiesʼ Elvis» goes out on the highest note possible, every bit as true to his image and original aesthetics as the last Beatles songs would be for the Beatles — «Sixtiesʼ Elvis» would be a significantly, if not completely, different animal that one may be free to endorse or decline, but may not be free to compare to the original beast who singlehandedly did more to raise and justify the self-confidence of young people than the entire teen-pop scene of the past fifty years. (And I’m only stating this in such an explicit manner so as to psychologically prepare us for forgiving the fellow his many, many sins against man’s intellectual evolution in the next decade).

The bass line on Baby I Don't Care caught me by surprise. I thought Spotify had jumped over to Sabbath's Children of the Grave for a second. Also love the fake restart of Milkcow, as well as the falsetto "Leeeeave" on the IV chord, and that "MILK IT!" leading into the solo break. Again, even on his "homogenized modern" stuff Elvis shows his versatility in adapting his voice to the song.