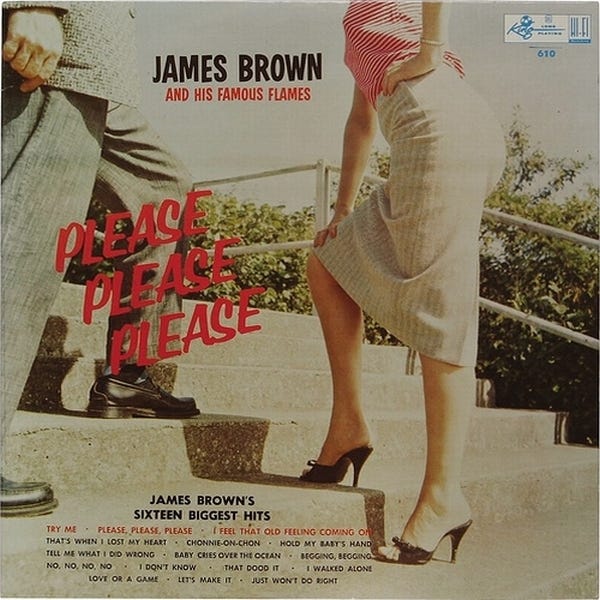

Review: James Brown - Please Please Please (1958)

Tracks: 1) Please, Please, Please; 2) Chonnie-On-Chon; 3) Hold My Baby’s Hand; 4) I Feel That Old Feeling Coming On; 5) Just Won’t Do Right; 6) Baby Cries Over The Ocean; 7) I Don’t Know; 8) Tell Me What I Did Wrong; 9) Try Me; 10) That Dood It; 11) Begging, Begging; 12) I Walked Alone; 13) No, No, No, No; 14) That’s When I Lost My Heart; 15) Let’s Make It; 16) Love Or A Game.

REVIEW

Nobody could ever argue, I suppose, with the simple truth that James Brown wasn’t exactly born for the three-minute single format. In his live shows, three minutes was typically what it took for him to just get himself and his audience into the groove, which he could then sustain for an indefinite amount of time, depending on how many cups of coffee — or something much stronger — he’d ingested in the past 12 hours. But back in 1956, the only way he and his Famous Flames could reach a mass audience was through records, and the only records he could make for the Federal label were three-minute singles. It was nice of his label, after almost three years of recording, to grant Mr. Brown the right for a full-fledged LP, but the only thing they put on that LP were the exact same A- and B-sides.

Unfortunately, the biggest problem with Brown’s early career is that the man found his showmanship much earlier than he found his music. Few, if any, of those early singles are particularly interesting from a rhythmic or melodic point of view — perhaps the most interesting thing about them is the ease (or maybe the desperation?) with which James and his buddies hop from ship to ship, investing here in doo-wop and torch balladry, there in old-fashioned rhythm & blues, here again in more modern rock’n’roll, with Brown alternately taking lessons from the Flamingos, the Dominoes, Little Richard, Fats Domino, Ray Charles, and whoever else he may see as a spiritually (and commercially) viable path to follow, imitate, and adapt to the peculiarities of his own persona. The Flames — quickly upgraded to the Famous Flames once word begins spreading just a tiny bit — loyally follow their leader wherever he takes them; some, most notably the original leader Bobby Byrd, also co-write the material (it is worth noting that the Flames declined to do straightahead covers, much preferring to rip off others’ musical ideas and pass them off as their own after introducing tiny variations).

The actual musical backbone, however, in those early years was not all that inspiring. Although the Flames played their instruments on stage, they were far better group singers than players, and, with the exception of guitarist Nafloyd Scott, on record their parts are taken care of by various local musicians, usually from the Cincinnati circuit where Federal Records were based. The results are as decent as they come, but nothing in particular, neither the rhythm section nor the brass nor any lead guitar or piano, ever stands out — it is clear as daylight that the only function of this music is to provide a reliable platform for the lead singer. And with so much diverse musical territory to be covered, even the lead singer is not always up to par. The fact that most of these early singles sank like stones commercially can hardly be blamed on the tastelessness or stupidity of the public, or even on the lack of promotion: the public clearly saw no need to be bothered with a new artist so obviously unsure of how to put his own stamp on well-known musical styles.

Of course, this was not the case with the very first of these singles, the one that rightfully gives its name to the entire LP as well: ‘Please, Please, Please’, not so much even an actual song as an extended vamp (inspired by the Orioles’ 1952 take on Muddy Waters’ ‘Baby Please Don’t Go’ and a Little Richard inscription on James’ napkin). It is musically simple as hell, and vocally direct as purgatory — pure, distilled soulful pleading, which, in his live shows, Brown would imbue with downright silly theatricality (most of us probably saw at least the TAMI Show version, with the Flames having to cool down their leader by throwing blankets around his shoulders and walking him across the stage). But precisely for these reasons, it worked — the same reasons, I think, why Jimmy Reed was so popular: sometimes you just gotta say it precisely as it is, without any extra embellishments whatsoever. Sometimes all it takes is a "baby please, please don’t go — I love you so", though it wouldn’t work nearly as well without the Flames drawing out that oooooh note in between the two parts, adding a touch of solemn gospel flavor to a broken man’s plea.

That said, already the second single, ‘I Don’t Know’, which was clearly aimed at repeating the same formula (at least, the number of times James chants "I don’t know" is clearly comparable with the number of times he belts out "please please please"), missed the mark completely — and it would take the man almost two and a half years to repeat the success of ‘Please Please Please’, during which he’d almost lost his record contract (you do have to admire the loyalty of the Federal label which let him release nine commercial flops in a row — a situation hardly imaginable in more modern times). Why exactly did that happen — what was so right with the first single, and what was so wrong with the next eight ones? I don’t know. (More correctly ‘I-ee-I-ee-I-ee-I-ee-I-ee I don’t know’).

What I do know, honestly, is that I have never been a huge fan of the «soul» aspect of James Brown’s artistic persona. James Brown as a hyper-energetic, one-of-a-kind showman, capable of electrifying the crowd with his crazyass dance moves and non-stop vocal fireworks (and, later on, working in perfect agreement with the innovative and just as captivating musical foundation), is easy to «get». But James Brown as a «soul brother», evoking genuine empathy and heartfelt emotion as he wails about broken hearts, romantic feelings, and deep devotion, is a concept that I have never managed to truly digest — there is simply too much theater, too much show, too much heart on too much sleeve for me to be able to take it seriously, as opposed to people like Ray Charles or Marvin Gaye, whose soulful declarations may not always be «sincere» in the straightforward sense of the word, but are usually believable.

For James, wherever he goes and whatever he does, it is always the show element that remains the most important; and ‘Please, Please, Please’, in its two minutes and forty seconds, did somehow manage to deliver a bit of a show — what with the words of the tune not even so much sung as they were fired into the microphone. ‘I Don’t Know’ is actually a bit more smooth and tuneful, but allegedly disc jockeys did not even want to play it on the radio while they still had copies of ‘Please Please Please’ lying around — it had nowhere near the same hammer-on impact: too screechy and theatrical to pierce their hearts, but not screechy and theatrical enough to beat them into a pulp.

Such is my tentative explanation, coupled with the fact that I, too, do not feel anything particularly special about ‘I Don’t Know’, or about ‘Just Won’t Do Right’, which is just a standard doo-wop progression with draggy vocals (the «hooky» chorus is given over to the unison of the Flames, while Brown just tries to sound as deep and passionate on the verses as possible, and it doesn’t really work). In fact, at this stage he does a more credible job on songs that sound straight out of the 1940s — ‘I Feel That Old Feeling Comin’ On’ is essentially a jump-blues piece in the style of Wynonie Harris, except that Brown’s vocals are an electrified tightrope compared to Wynonie’s rough, rowdy, much lower delivery, and you can feel that already at that stage the man was already trying his best to earn that "hardest working man in show business" title.

Problematically, after the first flops of the Soul Brother approach, Brown and the Flames began experimenting in all sorts of styles, which most people simply ignored. On ‘Chonnie-On-Chon’, for instance, he goes for a straightforward imitation of the all-night-party approach of Little Richard and especially Larry Williams ("big bone Lizzy, old aunt Fanny"), which is fun, but not particularly original — in this style, he can hardly hope to beat Larry’s sense of humor or Little Richard’s vocal attack. Even more ridiculous is ‘That Dood It’, a barely funny half-spoken anecdote which directly rips off Ray Charles’ ‘Greenbacks’ — ironically, the B-side of that single was a re-write of ‘My Bonnie’ (‘Baby Cries Over The Ocean’) that came out several months before Ray’s classic version; fun, but the straightjacketed pop format of the tune is simply not right for the free-form style of Mr. Dynamite.

‘That Dood It’ already comes from the 1957 sessions, by which time the original Famous Flames, fed up with the lack of success and with Brown’s egotistic behavior, had abandoned him altogether — something that may have been noticeable in the context of live shows, but hardly on record, where session musicians still rule the day and the Flames are always relegated to secondary, if not tertiary roles. The people may have changed, but the music remained the same mix of styles: a bit of old-fashioned doo-wop (‘Begging, Begging’, ‘That’s When I Lost My Heart’), old-fashioned R&B (‘I Walked Alone’, ‘Love Or A Game’), and old-fashioned jump blues (‘Let’s Make It’).

Just when the studio people, including Syd Nathan, president of King Records (of which Federal was a subsidiary), were beginning to have enough, Brown finally turned around and rebounded with ‘Try Me’ — the last of his singles to have been included on the LP. Differences between it and his previous slow ballads are subtle rather than revolutionary: ‘Try Me’ rides the same waltzing chord pattern that the Flames had favored since the beginning. But the song makes a harder pass at being soft — Brown’s delivery, first time in ages, is genuinely sentimental, as if he really is serenading under his love’s balcony (I like to imagine that he himself imagined this as a love letter to Syd Nathan while recording); the Flames are more crooning and angelic than ever before; and even session guitar player Kenny Burrell plays a series of soft and sweet licks, enough to melt a lady’s heart on the spot.

This was indeed the first time that James Brown did truly tame the beast inside — there are no signs of vocal hysterics whatsoever, just signals of I-wanna-be-your-dog submission (humble and courteous submission, that is, not Iggy Pop-style masochistic submission). If I didn’t know better, I might even be fooled, and apparently, so was the public, who did undergo a change of heart and agreed to try him, carrying the single to the top of the R&B charts. Note that it did not actually reverse Brown’s fortunes overnight — ‘Try Me’ was followed by at least another year of trials and tribulations, before ‘I’ll Go Crazy’ and ‘Think’ finally solidified the man’s presence on the musical scene. It was more like a temporary carte-blanche which helped James keep his footing and continue waddling on until he’d finally strike gold by finding just the right kind of music to go along with his personality. But it’s a curious phenomenon in its own right — apparently, in late 1958 the public was ready to accept Brown if he’d converted into a sentimental balladeer (imagine, for instance, if the Rolling Stones’ first hit single happened to be something like ‘As Tears Go By’ — just how much pressure would they have to withstand proving to the industry bosses that they were so much more at home reinterpreting Chuck Berry?).

In any case, although the album in general is no great shakes, it still presents an intriguing study of the early evolution of James Brown as a struggling, searching artist. Do make sure to arrange the tracks in chronological order while listening to it, so that it properly starts off with ‘Please Please Please’ and ends with the ‘Try Me’ single — or just ignore it altogether and go straight on to the detailed, well-documented collection of The Singles: The Federal Years 1956–1960, because, honestly, the selection principles based on which Brown’s early A- and B-sides were distributed across his first two LPs (this one and Try Me) elude me completely.

Only Solitaire: James Brown reviews