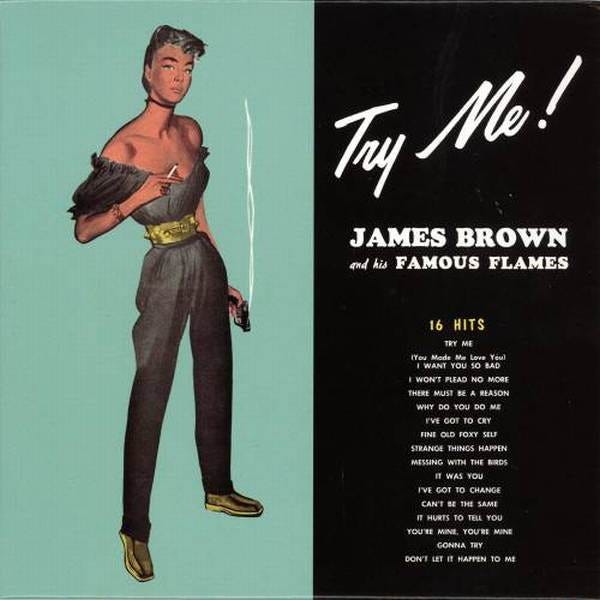

Review: James Brown - Try Me! (1959)

Tracks: 1) There Must Be A Reason; 2) I Want You So Bad; 3) Why Do You Do Me; 4) Got To Cry; 5) Strange Things Happen; 6) Fine Old Foxy Self; 7) Messing With The Blues; 8) Try Me; 9) It Was You; 10) I’ve Got To Change; 11) Can’t Be The Same; 12) It Hurts To Tell You; 13) I Won’t Plead No More; 14) You’re Mine, You’re Mine; 15) Gonna Try; 16) Don’t Let It Happen To Me.

REVIEW

Despite Brown’s seemingly inexhaustible energy and King Records’ generosity – once again, the LP contains a staggering sixteen numbers worth of material – Try Me! is, on the whole, an even less interesting collection than Please Please Please. For one thing, its most famous track — the title one, of course – had already been issued on the first LP; the only reason why it was included here is due to the fact that, in mid-1959, ‘Try Me’ was arguably the only song besides ‘Please Please Me’ that the average customer might have remembered of James Brown. In between October 1958, when ‘Try Me’ essentially saved the Flames from floundering, and mid-1959, the band put out two more singles (‘I Want You So Bad’ and ‘I’ve Got To Change’), both of which flopped, bringing the whole situation back to square. Once again, James had to be rather humiliatingly marketed along the lines of «the magnificent James Brown who gave us ‘Please Please Please’ and ‘Try Me’ which, believe it or not, are still played on the radio... here’s hoping that it won’t be one more year before he gives us something that will attract the public’s eye!»

For another, even if the various genre experimentations of 1956–57 were indeed amateurish, with a bit of a cleptomaniac feel to them, at least it was an intriguing spectacle, much like watching some hyper-enthusiastic start-up company come out with one blatant example of plagiarism after another, until finally striking gold with an original approach. By early 1958, however, Brown had begun narrowing the scope of his game, largely tossing out such genres as «pure» rock’n’roll or electric blues – realizing, perhaps, that he’d never be able to dethrone Little Richard or B. B. King, and that it would be best to concentrate on styles in which he felt most self-assured: (a) soulful balladry, with a steady doo-wop foundation, and (b) groove-oriented R&B, with a focus on «winding up» and ecstatic improvisation rather than disciplined vocal melody. This means that most of the 16 songs included here fall into one of these two categories — making the journey predictable — yet, unfortunately, most of them also follow pre-existing patterns, and with the three-minute length factor still in full force, rarely give the chance to either James or his musicians to truly show themselves off in full splendor.

Take ‘I Want You So Bad’, for instance, the immediate follow-up to ‘Try Me’. It’s a little faster, a little brassier, a little screechier (as if it were trying to re-introduce a bit of the ‘Please Please Please’ vibe into the overall balladeering softness), but on the whole, it is just an attempt to have another soulful hit in the same vein. Why didn’t it work? Perhaps it was precisely due to the middle ground approach — he «toughens up» the atmosphere to the extent that the song no longer has the silky, seductive, caring vocal overtones of ‘Try Me’ (which was probably Brown’s most successful ever infiltration of Sam Cooke’s territory), but at the same time does not toughen it up to the ecstatic levels of his first hit single. It’s a decent tune with a catchy vocal hook, but hardly anything more than that.

Or take ‘I’ve Got To Change’, the next single. Here, he decides to return to ‘Please Please Please’ territory in an utterly straightforward way — might as well have called it ‘I’ve Got To Change Back To 1956’ — so much so that even the Flames’ backing vocals slavishly repeat the lines of his first hit tune (ironically, this was recorded right after James had fired the entire band and replaced them with a new lineup!). If your hungry inner demon goes wild every time Brown rattles his decibels, ‘I’ve Got To Change’ will feel as impressive as anything — but if, like most music critics, you prefer to separate him from the crowd as one of the few R&B performers who always sought new ways of expression, you shall probably have to agree that this particular song seeks anything but new ways of expression.

In fact, looking over the sprawling track list even a few refreshing re-listens into the album, I find it problematic to single out any stand-out recordings. Almost perversely in a way, I think that the most memorable track for me remains the first one — ‘There Must Be A Reason’, the original B-side for ‘I Want You So Bad’ (is it any coincidence that they put the B-side first while sequencing the LP?). It’s a fast, boppy blues-pop ditty with doo-wop vocals, not unlike one of those ‘Don’t Be Cruel’-type «cutesy» numbers that Elvis recorded with The Jordanaires. Catchy, lively, with a sprightly sax solo in the middle, it seems to have more natural adrenaline to it than almost anything else on here... even despite being probably the last thing you’d want to associate with James «True Grit» Brown. There are a couple more like it on the album (e.g. the symmetrically placed album closer ‘Don’t Let It Happen To Me’ — the original B-side to ‘Good Good Lovin’), but nothing quite matches the tightness and energy of the opening number.

In terms of instrumental power, the best number is probably ‘It Was You’, recorded in December ’58 and actually issued as a single already after the LP — driven by a simple, loud, inspiring sax riff from J. C. Davis, which is the first thing you hear and will probably be the one thing you’ll take away and remember from this song, rather than Brown’s vocals (there is also an interesting «mini/malistic/-duel» between Davis’ sax and Bobby Roach’s electric guitar licks in the solo section). It is just not too often, on these early recordings, that the musicians ever get to outshine the frontman; although Brown is usually reported to have been working them to the bone, it wouldn’t really be until his funk phase that their voices would be allowed to raise above the master’s, so every instance, no matter how brief, of them reminding you that at least some of this music could be worth your while even without the lead vocalist, is treasurable.

Naturally, all of this stuff is still perfectly listenable — even the rare leftovers from all those other stylistic directions, e.g. the generic 12-bar blues ‘Strange Things Happen’, on which James Brown and his band pose as, let’s say, Little Richard wailing over a B. B. King-style lead guitar. If I am being distinctly sour, it is mainly so that you realize the impressiveness of the qualitative leap from Try Me! to Think! the very next year. There can be, I believe, but two schools of thought about James Brown — either that James Brown had a ton of hackish filler over the years, or that James Brown never had any filler in the first place, since what matters is really the «James Brown spirit» of things, and that spirit he carried in his pocket for all of his long and productive life. And if it is possible to belong to both those schools of thought at the same time, just give me two admission tickets for the price of one.