Tracks: 1) Just In Time; 2) He Was Too Good To Me; 3) House Of The Rising Sun; 4) Bye Bye Blackbird; 5) Brown Baby; 6) Zungo; 7) If He Changed My Name; 8) Children Go Where I Send You; 9*) Eretz Zavat Chalav U’dvash; 10*) Vaynikehu Gil Al Dema; 11*) Sinner Man; 12*) You’ll Never Walk Alone.

REVIEW

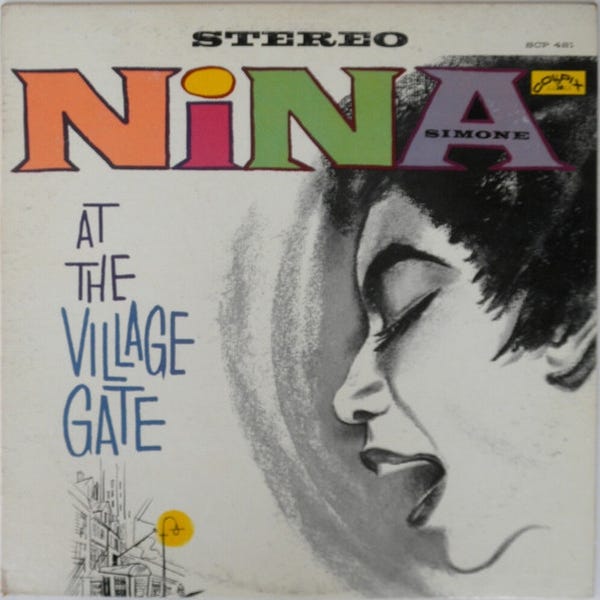

There is really no such thing as a bad Nina Simone live album (at least when we are talking about the peak years of her inner flame and creativity), but there certainly are outstanding Nina Simone live albums and then there are records which are just a bit less jaw-dropping in comparison, especially after you’ve assimilated the better ones. At The Village Gate, released by Colpix almost ten months after the actual gig (she held that particular residence at the Village from March 30 to April 27, 1961), is, unfortunately, an example of the latter, and I think that the unusually lengthy gap between the two dates is hardly a coincidence. A newspaper review of the Village Gate gigs stored at Nina’s website states thus: «Now the resilient Ms Simone can be heard at the Village Gate, where... her only problem is an amplifying system that loses the gentler nuances of her singing and buries her instrumental trio in a blather of echo». I fully concur with this assessment because this is exactly what you get on this album — sound quality that is undeserving of an artist of Nina’s stature. (And that is not to mention the usual interference of people chattering and silverware clatter, as expected from a club environment).

It’s all compensated with a spirit of authenticity, of course, and the problem of audience interference is not that bad — after all, The Village Gate is not exactly «B. B. King Blues Club & Grill», and people came there more to listen to the music than stuff themselves with gumbo — but the aforementioned «gentler nuances» are indeed harder to soak in than on the Town Hall record, although repeated listens can help. On the plus side, Nina’s variety and versatility come through in that there is almost no overlap between the songs she performs here and her earlier studio or live records — with the sole exception of ‘Children Go Where I Send You’, and even that one becomes a completely different beast live from what it used to be in the studio, extended as it is to more than twice the original running length.

Nina’s backing trio here is the same as on Forbidden Fruit, with Chris White replacing Jimmy Bond on bass, Bobby Hamilton manning the drums and Al Schackman running his tight guitar shop (‘Bye Bye Blackbird’ in particular brings him to the forefront, with a colorful speedy solo that can’t help but remind me, the perennial rock’n’roll, of the jazzy side of Ten Years After’s Alvin Lee about six or seven years later). As for the material, already the first, casual listen reveals that it is more or less evenly spread this time between standards and spirituals; notably, the CD reissue of the album adds two more traditional Jewish numbers and even an early rendition of ‘Sinner Man’, which precedes the classic recording on Pastel Blues by almost four years (I’ll save a detailed discussion of the song until that LP, but let me just mention that this earliest version is faster, jazzier, and a little more on the «playful» than the «epic» side; the only objective downside is the muffled sound quality).

There is no way to tell whether the running order of the tracks corresponds to the actual structure of the setlist, but it can hardly be a coincidence that the two most «mainstream» performances are placed at the start — ‘Just In Time’, a then-hot little number that was making the rounds in covers by Tony Bennett, Sinatra, Peggy Lee, and Blossom Dearie (Nina, of course, makes the lines "I found you just in time / Before you came, my time was running low" sound as if they were delivered by Puccini’s Mimi from her dying bed); and ‘He Was Too Good To Me’, a Rodgers-Hart classic dropped to an almost graveyard tempo — curiously, my ear picks up on chordal similarities between the bass-piano skeleton of the song and ‘The Long And Winding Road’, though I am not sure exactly how relevant that connection might be (of the two main Beatles, it is usually John who is called more of a Nina Simone fan than Paul — then again, Nina herself did eventually record ‘The Long And Winding Road’ for her last album, so maybe not that much of a random coincidence?).

From these two solid, if rather poorly sounding numbers, Nina then launches into an equally graveyard-tempo ‘House Of The Rising Sun’, in a benevolent gesture that almost reads like a «that was then, and this is now» statement — given her temporary migration from Town Hall to the Village Gate, where the customary audience would most likely prefer hearing this kind of material to Rodgers and Hart. Not that they did not enjoy Rodgers and Hart — in Nina’s arrangements, Rodgers and Hart end up sounding like a couple of 19th century gravediggers anyway — but ‘House Of The Rising Sun’ was, of course, the song-du-jour in 1961, with Joan Baez and Dave Van Ronk delivering their interpretations and subconsciously waiting for that young Bobbie whippersnapper to deliver his, and Nina does her best to steal the show as she leaves the musical backing to her bass and guitar players, concentrating solely on the vocals. As you can probably predict by this point, she internalizes the pain rather than let it all hang out, which automatically means that this version stands no chance of ever surpassing The Animals in the faint wisps of popular memory. But if you ever wondered about what a «haunted house version» of the song might feel like, Nina’s take might just bring you right to that spot, as she sounds more like a gothic ghost of the protagonist than a person of flesh and blood.

This spookiness congeals later on with the transition to ‘Brown Baby’, Oscar Brown’s classic modernization of the vibe of ‘Summertime’ with more acutely pronounced social overtones. Rather than following Brown’s own shorter and more anthemic version, Nina takes her cues from Mahalia Jackson’s recording, but tones down the power and makes the song actually sound more like a true lullaby. If I have not mentioned it before, it would be worth noting now that Nina’s stand on social justice was never accompanied by rose-colored glasses: she is great at taking the most idealistic songs ever written and subverting that idealism until it all chills you to the bones rather than inspires you, so her ‘Brown Baby’, in a way, feels like the last words of a mother spoken to her baby before the both are marched into the gas chambers, rather than a song of hope for a better future for humanity. (Okay, if that assessment does not make you want to grab the record, I’ll have to do a serious reassessment of the efficacy of my baiting powers).

The only problem is that after the chill of ‘Brown Baby’ (during which even the carefree audience of the club, so busy chatting and clattering silverware during the instrumental performance of ‘Bye Bye Blackbird’, sits quiet as a mouse), the equally chilly chill of the old spiritual ‘If He Changed My Name’ feels like a slightly paler rehash of ‘Brown Baby’, setting exactly the same mood. But at least the two are separated by ‘Zungo’, a short, percussion-heavy cover of a recent number by Nigerian drummer Babatunde Olatunji — and then followed by a fast-paced, thunderous, jam-like rendition of ‘Children Go Where I Send You’ which completely wipes the borders between counting-out rhymes, spirituals, and bebop jazz.

Throw in the Hebrew chants attached as bonus tracks, and one big advantage of At The Village Gate that Nina’s previous albums do not quite have is its incredible diversity. From showtunes to deep folk, from deep folk to modern jazz, from modern jazz to African and Near Eastern musical traditions, from 19th century to vividly modern spirituals, and then wrapping it all up with her familiar Rachmaninoff-style rearrangement of ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ (bonus track), she gives a performance that is pretty much impossible to categorize, genre-wise. At the same time, credit must be given to Nina’s overall savviness, as she clearly recognizes the type of audience for which she is playing — which is why At Town Hall focuses more on show tunes, At Newport pulls stronger into the jazz & blues segment, and At The Village Gate pays a much more pronounced homage to the various folk scenes, old and new. Yet none of these performances are «purist» in nature — it’s all in the mix ratios of the ingredients rather than the ingredients themselves.

"You ever been to a revival meeting?" she asks after the first couple of verses to ‘Children Go Where I Send You’. "I bet you don’t even know what I’m talking about", she adds with a condescending sneer after a fairly ho-hum response from the crowd (I can just picture her visually establishing that kind of moral superiority over a bunch of pale-skinned, bespectacled college boys and girls of New York City). "Well you in one right now!" she then concludes triumphantly before launching into the next verse. However, as exciting as it sounds, I cannot help but detect a misleading trace here: Nina Simone is not Mahalia Jackson, nor even Aretha Franklin, and her idea of a «revival» is certainly not to recreate an actual church atmosphere, which requires at least two key elements from the performer — unsimulated faith and free-flowing joy — neither of which, I am afraid to say, would ever come naturally to Ms. Simone (I would not want to make assumptions about her actual and deeply personal religious beliefs, but cracking a smile was a really hard job for her, and if she did crack one, you would probably usually wish she just didn’t).

She does embrace the concept of the «spirit», though, and the idea of being possessed by it during the performance — it’s just that her personal archangel (or Patronus, if we switch to the modernized version of the code) was born on a rainy and cloudy day, certainly not a warm and sunny one. But not a particularly thunderous, either: neither ‘Children Go Where I Send You’ nor even ‘Sinner Man’ here are really about vengeance and retribution and the fires of Hell. It’s more about a general kind of ecstatic trance, where you channel all of your accumulated anger and pain into pure dynamic energy and let it all out in the open air, rather than go for some specific target. In a way, it’s just a very special form of musical psychotherapy — and I would feel really hard pressed to come up with any other name of a musical artist around 1961–62 whom I could openly call a «musical psychotherapist». Perhaps that should be the name of the overall musical genre that Nina was creating on these albums? «Psychotherapeutic pop»? Make it «shrink-pop» for short.

Still, I want to conclude the review by reiterating that, out of the trilogy of Nina’s early live albums, At The Village Gate is my least favorite; not just because of poorer sound quality (this can eventually get used to), but also because some of the performances become predictable by this point, and because not everything works equally fine in this aggressively diverse setting (I am definitely not a fan of the Jewish numbers appended as bonus tracks, and, as I already mentioned, ‘If He Changed My Name’ mood-wise feels like a weaker echo of ‘Brown Baby’, just one track apart.) Perhaps it just catches Nina in a transitional state, not yet ready to relinquish her early status as an innovative standard-carrier but not yet on equally easy terms with the new trends and developments in popular music. Then again, perhaps I’m just rambling and it is really just the average sound quality that throws me off so much. No matter. The album is still a must-hear for anybody who thinks that Greenwich Village in the early 1960s was all about pretty girls and scruffy guys singing Appalachian ballads on badly tuned acoustic guitars — as usual, reality is always more complicated than our hastily formed impressions of it.

Only Solitaire reviews: Nina Simone

An off topic question: can current behaviour of an artist influence your attitude towards their earlier work? Recently I've realised that despite Pink Floyd being my favourite band for a very, very long time, now I'm never in the mood to put on any of their classic albums as it immediately connects me to the Rodger Waters of today and to the unpleasant wondering whether even "Animals" didn't actually have the same message that he is spreading now.

“the CD reissue of the album adds two more traditional Jewish numbers and even an early rendition of ‘Sinner Man’, which precedes the classic recording on Pastel Blues by almost four years (I’ll save a detailed discussion of the song until that LP”

George, have you estimated when you will review it? Yours is a gigantic task. Congratulations anyway