Tracks: 1) Summertime; 2) Congratulations; 3) Baby You Don’t Know; 4) I Can’t Stop Loving You; 5) Excuse Me Baby; 6) History Of Love; 7) Today’s Teardrops; 8) Mad Mad World; 9) Thank You Darling; 10) Poor Loser; 11) Stop Sneakin’ ’Round; 12) There's Not A Minute.

REVIEW

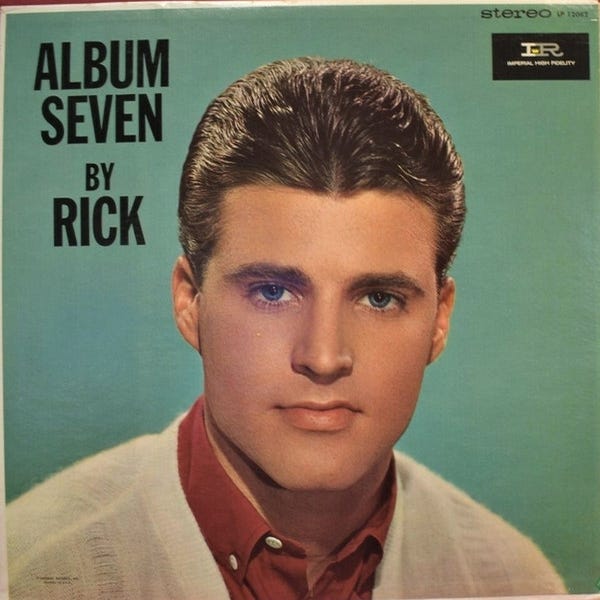

Ricky’s first single in the year of the Cuban Missile Crisis was ‘Young World’, another Jerry Fuller contribution which partially managed to rectify the bland blunder of ‘A Wonder Like You’ — at the very least, it returned Nelson back to the Top 10, and it continued to demonstrate that the boy-turned-man clung on to a more refined sense of taste than most of his contemporaries. Jangly guitars, a delicate, but sharp and raw instrumental break from Mr. Burton, and a modest, restrained arrangement with a well-pronounced vocal hook — the song was written in classic Buddy Holly / Crickets style, and delivered by Ricky with the usual reticent charisma. And as banal as that particular hook might be ("It’s a young world / When you’re in love, you’re in a young world"), well, it was a young world back in 1962, want it or not, and the song captured that feeling reasonably well. Granted, if you listen to the song long enough, you might begin to convince yourself, like I am doing right now, that it was basically just a variation on Sam Cooke’s ‘Cupid’. But that’s for the courts to settle, if they ever run out of new copyright suits (hah!); for me, the important thing is that a Ricky Nelson love serenade appeals to a whole other type of personality than a Sam Cooke one, and while Sam is clearly the superior singer in terms of range and versatility, when it comes to a love serenade, the quiet, melancholic murmur of Nelson can, under certain circumstances, feel more empathetic than the lilting, in-yer-face croon of Cooke. (In an ironic, but somewhat predictable, sociopolitical twist, ‘Young World’ charted higher than ‘Cupid’ in the US, but lower than it in the UK).

Seriously more puzzling and eyebrow-raising than ‘Young World’, though, would be its B-side, a cover of ‘Summertime’ which would also be chosen as the opening track on Ricky’s seventh LP. Oh no, not another cover of ‘Summertime’, right? But in all honesty, this one deserves to be heard, because not only is it one of the first, if not the first «hard-rocking» (well, relatively so) reinvention of the tune, but its opening bass riff, played, as usual, by Joe Osborn, is the exact same riff that would four years later form the basis for ‘(We Ain’t Got) Nothin’ Yet’, the well-known hit by The Blues Magoos, and four more years later — the basis for ‘Black Night’, the even better known hit by Deep Purple. In fact, as far as I know, Ritchie Blackmore himself never hid the fact that he lifted the ‘Black Night’ riff directly from Ricky’s arrangement of ‘Summertime’ (bypassing any Blues Magoos references).

Not that I feel any incentive to accuse Blackmore or the Blues Magoos of dirty robbery — well, maybe robbery it was, but one motivated by a noble purpose. The thing is, this cover feels weird because Ricky sort of struggles to sing the vocal melody over the instrumental backing; it is not altogether unthinkable that ‘Summertime’ can be made into a hard rock anthem (Janis and Big Brother came very close to that ideal), but even then it has to be a hard rock lullaby, not a galloping, rabble-rousing rocker. Clearly, the Osborn riff functions much more naturally as a part of ‘Black Night’ than it does here. On the other hand, it’s hard not to admire the audacity — how was it that, so totally out of the blue, Ricky and his little band decided to up the ante on the darkness, and reinvent ‘Summertime’ as a lightly broodin’ mini-nightmare? With Burton’s screechy guitar leads, somebody else’s swampy harmonica, and near-tribal percussion this ‘Summertime’ is more fit for a secluded log cabin in the depths of Louisiana than... oh wait, I guess a black tenement in Catfish Row isn’t that far removed, atmosphere-wise, from a secluded log cabin in the depths of Louisiana after all.

Anyway, fitting or not, this particular ‘Summertime’ might be as adventurous as Rick Nelson ever got in his generally not adventurous career — and the fact that he did so in 1962, the peak year of «non-adventurousness» in US popular music, should not be forgotten. Had there been at least a small bunch of tracks on Album Seven to follow similar lines of creativity, we might have to single it out for a special Medal of Honor; unfortunately, the LP drops the bar back again as quickly as it raises it with the opening bass riff, and the rest of the material is predictable — quality stuff, for sure, at least for the standards of 1962, but... predictable. Which only makes the mystery of this particular ‘Summertime’ all the more intriguing, but, unfortunately, the relative lack of retro-interest in Mr. Nelson prevents us from learning the particular circumstances in which the recording was conceived. I’d definitely like to know who was ultimately responsible for this special take — and how the heck they managed to get approval from Imperial Records.

Most of the other songs on the LP come from a series of recording sessions stretching from July to December 1961, with Ricky and/or the record label people sorting through the stockpiled takes and selecting what they thought would work (not that there was a huge amount to choose from, but published sessionographies show that quite a bit of material was left unreleased, then eventually vanished forever before it could be salvaged for the age of Anthologies and Deluxe Boxsets). With the exception of ‘Summertime’ and a cover of Don Gibson’s ‘I Can’t Stop Loving You’ that I could very easily live without, all the songs are fresh contributions from the usual suspects: Jerry Fuller (sometimes in collaboration with Dave Burgess) supplies four tracks, Dorsey Burnette yields two, and Baker Knight (the hero of ‘Lonesome Town’), Clint Ballard Jr. and Gene Pitney each give one. As a slight bonus, this is the first LP of Ricky’s to feature a song from Jackie DeShannon (‘Thank You Darling’), though it’s hardly one of her more memorable tunes.

In fact, I wouldn’t call any of this stuff memorable — absolutely nothing here beats the opening surprise of ‘Summertime’ — but pretty much all of it is very, very consistently pleasant and tasteful. It’s largely what I’d call «mediocre-passable» songwriting: lyrics and melodies with only as much originality as it takes to evade a copyright suit, stuff that a corporate songwriter grinds out on a daily basis with 99.5% perspiration, 0.5% inspiration. (As a music reviewer who used to write on a self-appointed schedule, I fully sympathize). A little Elvis here and there, a bit of Buddy Holly, a touch of the Everly Brothers, all of this wrapped in the nice guitar arrangements of James Burton and graced with Rick’s predictable, but never annoying or exaggerated singing. For 1962, with commercial pop so fully dominated by bombast and sentimentality, being able to stick to this kind of style is almost like a heroic achievement.

Could I actually recommend any of the individual songs? Well, perhaps Fuller is trying a bit harder than his songwriting factory co-workers: ‘Congratulations’ — nothing to do with the later Rolling Stones song by the same title, although the subject matter of both songs is exactly the same — is particularly catchy, and both the lyrical flow and Nelson’s micro-modulations of the vocal melody almost make you feel for the poor heartbroken protagonist. "The day you came into her life / That’s when our love died / Congratulations, and I hope you’re satisfied" — I sure am, because there’s just something truly pleasing about how these individual clichéd phrases fit together. Also, "just how you took her love from me I’ll never understand" is certainly the slogan of every shy, polite, sensitive guy around the globe, and Ricky is just the right figure to deliver it. Somebody like John Lennon would handle things in a completely different manner. Catch you with another guy, that’s the end little girl and all that. Oh, also, the bridge section is very strongly influenced by ‘Save The Last Dance For Me’, which is probably more than just a thematic coincidence. The protagonist in that song wasn’t exactly suffering from an overload of self-confidence, either.

Of the other Fuller songs, ‘Baby You Don’t Know’ is a pop-rock throwaway — literally the same song as ‘Congratulations’, only delivered at a faster tempo and deprived of a bridge, which gives Burton enough space to deliver an aggressive guitar break, but not much else — but ‘History Of Love’ is one of those fun «alternate look at world history» numbers, like ‘Hard Headed Woman’, only without the misogynistic twist: "And then I read of Marie Antoinette, she lost her head over Louis / But I lose mine over you each day because I love you truly", that sort of thing. Melodically, it’s also built over Buddy Holly / Crickets’ legacy, with Burton doing another fine job and the entire band going for a pleasant summer day vibe. Nothing to go ga-ga about — nothing to scoff or despise, either.

Gene Pitney’s and Aaron Schroeder’s ‘Today’s Teardrops’ is also derivative as hell (‘Just Because’ — the main verse, and another Buddy Holly bridge, plus the main guitar riff leans heavily on ‘Mystery Train’), but the groove is fun, what with that non-stop pounding percussion and tight-as-hell piano and guitar; just a smashin’ cool sound with lots of uplifting potential. Meanwhile, Dorsey Burnette tries to channel some of the old Rock’n’Roll Trio spirit into ‘Excuse Me Baby’, and once again resurrects the Buddy Holly jangle on ‘Mad Mad World’; Baker Knight’s ‘Stop Sneakin’ Around’ is almost the same song as ‘Excuse Me Baby’, but almost as fun; and Clint Ballard’s ‘There’s Not A Minute’ ends the album on a sentimental note, with Ricky double-tracking his vocals as if he were both Everly Brothers at once — and I’d say he almost pulls it off.

Admittedly, it’s very easy to look at all of this from the vinegar side, call it a limp approximation of / cheap substitute for classic rock’n’roll, and walk away with a superior attitude; that’s probably what I myself would have done twenty years earlier, looking at it in the context of the great rock’n’roll hits of the Fifties. In actuality, though, you have to look at it in the context of 1962 — the year of swooping strings, puffed-up teenage dramatics, and let’s-twist-again — as well as the context of Ricky’s own earlier albums; and in that particular light, Album Seven never feels like any kind of betrayal of any kind of musical values. On the contrary, it’s «steadfast, loyal and true» in an age that is so often associated with «regression».

Only Solitaire Reviews: Ricky Nelson

> ‘Congratulations’ — nothing to do with the later Rolling Stones song by the same title

Also nothing to do with the later Travelling Wilburys song of the same name, despite sharing the exact same first line, though for some reason I can sense some similarity (though I guess there are only so many ways to pronounce "Congratulations for breaking my heart" to rock music).

Not to mention the fact that "Album Seven" is very meta in a proto-Public Image Ltd. kind of way.