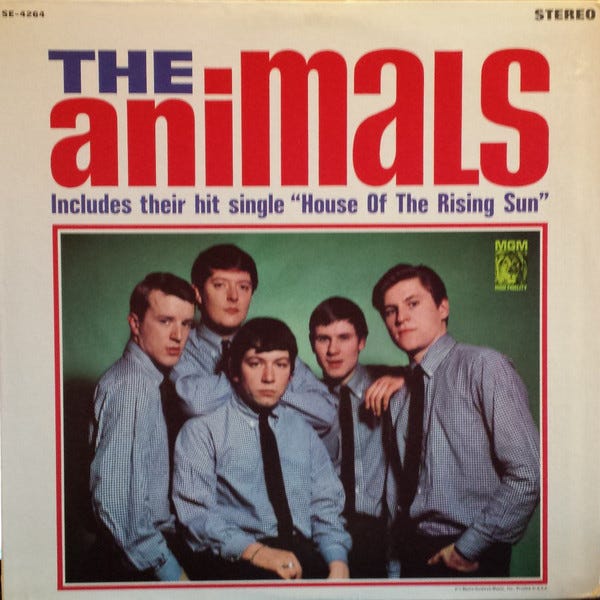

Tracks: 1) The House Of The Rising Sun; 2) The Girl Can’t Help It; 3) Blue Feeling; 4) Baby Let Me Take You Home; 5) The Right Time; 6) Talkin’ ’Bout You; 7) Around And Around; 8) I’m In Love Again; 9) Gonna Send You Back To Walker; 10) Memphis Tennessee; 11) I’m Mad Again; 12) I’ve Been Around.

REVIEW

The simplest way to lay one’s hands on the Animals’ self-titled debut and the two American albums that followed it is through the commonly available 2-CD EMI set entitled The Complete Animals; keep in mind, however, that it is «complete» only as far as their 1964-1965 recordings for MGM / Columbia, i. e. the Alan Price era, during which the band had not yet turned into a custom-made vehicle for advertising the limitless ego of Eric Burdon; instead, it was simply one of the most blunt, brutal, and soulful British rhythm’n’blues combos that, some might argue, could only really have emerged out of an appropriately blunt, brutal, and soulful location — like Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

This means that at least for this incarnation of the band it makes sense to remember at least a few separate identities. Eric Burdon, at this point, is just the frontman, though already an essential part of the band — its rough, rowdy, ballsy vocal piece, and the primary communicator of those sacred musical messages from across the Atlantic. Alan Price is the band’s resident keyboard player with a strong preference for the organ, capable of extracting smokey, moody atmospheres that owe a lot to Ray Charles but display a ton of individuality. Hilton Valentine is the guitar player — not a particularly special one, hardly in the league of Clapton when it comes to technique or Keith Richards when it comes to aggression, but it was Hilton Valentine who put on record those classic arpeggios for ‘House Of The Rising Sun’, and this already counts for something. And the rhythm section is John Steel on drums, who is mostly known as the longest-playing Animal in the history of the band (what a coincidence with the name of the Muppets’ resident drummer!); and Chas Chandler on bass, who is mostly known as the future manager of Jimi Hendrix. This is not to say they are a bad rhythm section or anything — they do their jobs very well; they just rarely, if ever, try to stand out.

As is the case with most British bands of the period, it is of no principal importance whether the reviews be centered around their US or UK discographies, since none of the early albums were intended as conceptual entities. I do not have a rigidly enforced principle here — it all depends on specific circumstances; but as for the Animals specifically, following the band’s US discography is a bit more comfortable, since US LPs were more numerous, packing all the songs that were only released as singles in the UK — although it does come at the expense of a little chronological chaos. Anyway, I am going to use as a pretext the fact that The Animals actually came out about one month earlier in the States than it went out to market in the UK. The major difference between the two versions was that the US one predictably included the A- and B-sides of the band’s first two singles (as well as ‘Blue Feeling’, which eventually ended up as the B-side to ‘Boom Boom’), while the UK version had five different LP-only songs in its place — which would, in due turn, be released on later LPs in the States. (It’s all very simple, really. It also encourages you, the penniless young American teenager, to go out and buy almost the same album as a home product first and then again as a UK import).

Like most respectable British R&B bands of the time, the Animals had very little incentive to write their own songs — like the Stones and the Yardbirds, they would rather think of themselves as responsible for channeling the spirits of the classic blues and rock’n’roll masters across the Atlantic. At least Andrew Loog Oldham, savvy enough to perceive that original songwriting was the sole key to a stable and promising future, had goaded his protegés into writing ‘Tell Me’ to put a small stamp of personal interest on The Rolling Stones; Mickie Most, the producer of the Animals, had no such hold over the rowdy boys of Newcastle, and was happy enough to have them handle Little Richard, Chuck Berry, and Ray Charles as long as they could transfer a bit of that rowdy live spirit on record. So how does the record hold up today?

Pretty damn fine, I’d say. Somewhere at the intersection of Burdon’s voice and Price’s fingers, the Animals struck upon a thoroughly unique sound, unashamedly appropriating (in the good sense of the word) these songs and making even such universally covered chestnuts as Chuck’s ‘Around And Around’ or Ray’s ‘The Right Time’ well worth your time in their interpretations. Alan Price, in particular, is almost singlehandedly responsible for turning the electric organ into a rock weapon as powerful as the electric guitar. His playing may be technically less advanced / inventive and more «rootsy» and dependent on well-established blues patterns than that of his main contemporary competitor on the instrument — Rod Argent of the Zombies — but, for one thing, Price came first, and, for another, we are talking straightforward rhythm-and-blues here, while Argent’s greatest achievements arguably lay beyond that particular realm.

On the record’s faster numbers, Price’s instrumental passages, with the legato overtones of the notes diffusing across one another, practically create an atmosphere of proto-psychedelia that must have driven rock’n’roll dancers punch-drunk in 1964 and still feel amazing today — check out his work on Ray Charles’ ‘Talkin’ ’Bout You’, where he is allowed to take a minute-long solo that already starts out punchy and fast and then just keeps building and building, with the organ waves occupying every metric inch of the sonic space, leaving you no place to breathe. On the slower ones, he knows how to make good use of the volume level, keeping it hush-hush potentially-threatening for a while and then breaking out into a frenzied flurry of notes before going back to a subdued grumble (John Lee Hooker’s ‘I’m Mad Again’). And even if he largely uses the same instrument and the exact same tone through the entire record, he knows well how to flesh it out in very distinct and different moods — playful, sorrowful, menacing, ecstatic — to ensure that it never gets boring.

As for Eric Burdon, I feel it is quite a challenge to dissect and describe the precise secret of his singing. For one thing, it is fair to say that he never had that much range to his voice, or that his trademark «powerhouse» delivery, stunning and even shocking as it might have been around 1964, has long since been beaten in terms of decibels by far throatier powerhouse vocalists, such as Noddy Holder of Slade (do note that most of those come from Scotland — must be all those barrels of ale that really make the difference). My best guess is that it is actually the combination of the powerhouse approach with a certain amount of refined intelligence — a phrase that would hardly be appicable to Noddy Holder’s singing — that does the trick. Burdon knows not just to belt it out, but to actually play around with his voice, creating an intrigue for the listener. He also knows the value of silence just as he knows the value of all-out screaming; and he, perhaps best of all the early British rock’n’rollers, had mastered the voodoo art of classic bluesmen and R’n’B-ers with their capacity of subtly guiding the audience into a trance-like state through mantraic repetition of the simplest phrases.

Indeed, it is hardly a coincidence that the Animals were the first British band to allow themselves, in the studio, to record an uninterrupted 7-minute jam — based on Ray Charles’ ‘Talkin’ ’Bout You’ and then eventually transitioning into the Isley Brothers’ ‘Shout’. When it is not Price in the spotlight, jamming those keys like there was no tomorrow, then it is always Eric, blasting out his mini-mantras in tightly wound spirals, juggling one in the air for exactly as long as it takes to keep her fresh and then quickly exchanging her for another, even louder and screechier one. If those seven minutes felt like two or three to you, as they did to me, you know you are on the right track. (Too bad that the original pressing of the album only had a ridiculously condensed 2-minute version; the entire recording remained officially unissued until 1966, when it appeared on a compilation, thus unjustly depriving the Animals of setting an early record).

In between these two masters of the trade, even such thoroughly lightweight tracks as the band’s very first single, ‘Baby Let Me Take You Home’, are delightful in their own right. The song was copped by the band from Dylan’s 1962 acoustic arrangement of Eric Von Schmidt’s ‘Baby Let Me Follow You Down’ and is still listed in textbooks as an early example of the folk-rock genre (allegedly it even bounced back on Dylan himself, inciting him to go electric, though it is always unclear whether the Animals or the Byrds were a bigger influence); I think, however, that the song’s finest trick is to unpredictably shift gears for the coda and transform itself into thirty seconds of first-rate rave-up, borrowed from ‘It’s Alright’ — for no other reason than to just put folk music and rhythm’n’blues in bed with each other and see what happens. (Spoiler: nothing particularly pornographic, it’s more of a Manet’s Breakfast On The Grass effect).

Personally, I prefer the Animals at their darkest, especially since they really like cranking up their psycho-theater to the max: thus, ‘I’m Mad Again’ takes the vampish embryo of a song which it was in John Lee Hooker’s recording from 1961 and builds it up to a multi-layered, explosive performance. I revere John Lee Hooker as much as anyone, but it is an objective fact that, having heard 20 seconds of the song, you have pretty much heard it all; the Animals bring in their own dynamics, resulting in what is arguably the most believable impersonation of a nervous breakdown in British pop music up to that time. Alas, the only catch is that the darker stuff is still in an overwhelming minority on this album: in their earliest days, the band preferred to excite their audience and rock down the house, rather than hypnotize it into a state of deep shock by plunging into the abyss of darker emotions. Then again, moping and brooding and acting all Goth-like was hardly a good way to build up a loyal following in the sunny old days of 1963-64.

That said, of course, few things could be darker than the band’s legendary take on ‘The House Of The Rising Sun’, a once-in-a-lifetime performance which has not lost one ounce of its terrifying power ever since. Its historical influence can hardly be overrated — it may not have singlehandedly invented «folk-rock» or any other genre, but it certainly was one of the earliest indications that rebellious teenage pop music could come equipped with genuine brains and authentic soul as opposed to the generally expected youthful brawn and adolescent lust. Incidentally, it also served as an important watermark in the evolution of rock lyrics: apparently, Eric Burdon did not feel nearly as comfortable as Dylan about singing "it’s been the ruin of many a poor girl, and me, oh God, I’m one", and had to change ‘girl’ to ‘boy’ — immediately, though unintentionally, transforming the song from a tragic, but predictable, folksy lament of a brothel-confined girl with family troubles into the equally tragic, but far more mysterious — mystical, in fact — plight of The Disspirited Young Man, in which "The House Of The Rising Sun" becomes an abstract allegory of the same nature as "Hotel California" would be twelve years later. (Unless you prefer to go for a more straightforward explanation and assume they are just singing about a male brothel... hey, don’t blame me, I even browsed through a master’s thesis on male prostitution in New Orleans to ascertain that there were probably no such things in The Big Easy, as opposed to male prostitution per se).

The historical importance of the track may also be reinforced by mentioning the record-breaking length of 4:29 for a single release (kudos to Mickie Most for greenlighting the idea), even though the US version still ruthlessly cut the song down to a three-minute length, and that was also the way it first appeared on the album; I don’t think I even heard the short version, and I have no desire to — unlike certain lengthy Dylan ballads, where the only difference between certain verses lies in their lyrics, ‘The House Of The Rising Sun’ guides us through a perfectly orchestrated series of rises-and-falls, with the song’s culmination midpoint represented by Price’s solo, after which the song gradually rebuilds itself up through the next three verses. Cutting out even one of them is like fast-forwarding over a stripper removing a piece of her clothing, if you’ll pardon the crude, but apt analogy (we are talking about The House Of The Rising Sun, after all).

From a purely emotional standpoint, though, the song is a prime beneficiary of what could be defined as the key ingredient to the success of classic Animals records: the Battle of Egos between Burdon and Price. On almost every one of these early tracks, the two key members of the band vie for our attention, and even though it may seem as if the ball is always in the singer’s court by definition, each time the spotlight — even briefly — passes on to the organ player, there is a chance that he might leave you so stunned, it’ll take you a while to pick yourself off the floor and remember about the vocalist’s existence in the first place. On ‘House’, Price starts his anabasis off on a slow, deliberate note, with the organ part surreptitiously beginning to creep in not earlier than the beginning of the second verse — then keeps building up the volume, speed, and polyphony with each bar, so that we are perfectly ready by the time he breaks into the solo, which is probably quite close to the way it might have sounded, had J. S. Bach himself been offered a nice paycheck to put it on record. And it is Price, not Burdon, who gets to have the final word as well — with a series of gradually decelerating, dying-down, tragically submissive chords ending in an almost psychedelic final puff of organ smoke.

None of which should downplay the part played by Burdon, who gives a Shakesperian, epically tragic reading to the tale — realising, in a fairly common and accessible manner, its Grand Pathos potential which was already hinted at in Dylan’s earlier reading; but Dylan’s vocal tone and manner of singing is, as we all know, very much an acquired taste, and even if it was really Dylan who first transformed the song from Ur-Hamlet into The Tragedy Of Hamlet, just to use an actual Shakesperian analogy, there is just no getting away from the fact that the Animals’ completion of the tune will always have much more mass appeal, working out a beeline for your emotional centers whereas Dylan’s version takes a much more crooked and twisted path.

It is fairly odd, though, that ‘The House Of The Rising Sun’ pretty much stands out all alone in the Animals’ catalog. One might have expected the band to try and capitalize on its success by seeking out even more old folk tunes to cover — yet they never opted for such a turn, instead continuing to focus on the blues, soul, R&B, and rock’n’roll material that was, in general, much closer to their rowdy Scottish hearts than all that Greenwich Village stuff. Yet I must say that, in general, the Animals are at their best when they try to be dark, moody, and soulful than when they try to just raise a ruckus and rock out; and for that reason, this debut LP does not cut it nearly as well as the follow-up records, because it leans way too heavily on the merry party stuff. For instance, while their cover of Chuck Berry’s ‘Around And Around’ is generally tight and exciting, it does not compare well to the Stones’ interpretation — Price and Burdon do the best they can, but the song begs for a more provoking, sleazy vocal like Jagger’s, and a nastier, ruffian-like guitar tone like Richards’. Nor am I a major fan of their ‘Memphis, Tennessee’ (admittedly, few, if any, artists could add anything particularly interesting to that one after Chuck’s original — though I do like that rigorous guitar flourish concluding each verse).

On a minor side note, it is amusing to sometimes see the band «adapting» those across-the-ocean imports for their young and ignorant British audiences (and, conversely, creating communicative problems for everybody else): for instance, Timmy Shaw’s early 1964 hit ‘Gonna Send You Back To Georgia’, a sarcastic lyrical expansion of the old «you can get X out of the country» adage, is covered very close to the original, but renamed as ‘Gonna Send You Back To Walker’, where Walker is actually the residential area of Newcastle in which Burdon was born — which does give us a better understanding of the true feelings of Mr. Eric toward his native turf. (They also have make an important change of preposition, substituting "bring you from the South" for "bring you to the South". Wonder what all the confused American kids were thinking when this whole thing got re-imported to them). At least ‘Memphis, Tennessee’ is not turned into ‘Blackburn, Lancashire’ or whatever, though, admittedly, the lyrics to that one are nowhere near as culture-specific.

Ultimately, on the basis of a song-by-song battle, The Animals would inevitably lose to The Rolling Stones, being more blunt and brawny in its treatment of material which the Stones tried to present as nasty and naughty. Yet the Stones’ debut did not have anything even remotely close to the power of ‘House Of The Rising Sun’, which is, on its own, the equal of pretty much everything the Stones released in 1964, and would have immortalized the name of the Animals even if they did not record anything else (and, for that matter, most people out there probably do not even suspect that the Animals recorded anything else — perhaps a few might recognize or remember ‘Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood’ or ‘We Gotta Get Out Of This Place’?.. not really sure). This fact alone makes both bands equi-important for 1964, with the Stones setting new standards of freedom and provocation for popular music and the Animals setting up a milestone in the transformation of popular music into the thinking man’s playground — though, unfortunately, they failed to capitalize on their own achievement until it was too late for anybody to care all that much.

Only Solitaire: The Animals reviews

In my youth in the 80s, my love for 60s music lead me to often imagine that I was born 20 years too late, and that if I had lived to experience the bands that I was falling in love with (Byrds, Beach Boys, Who etc) first hand, I might have been inspired to pursue music more passionately. I'd like to think that if I were a 13 year old in '64, it would be this band--singing that haunting folk song--and not the Beatles or Stones that would have activated the latent musician in me to pick up an electric guitar and embark on the hard road of rock discovery. Its timelessness (much like Whiter Shade of Pale in a later period) is rooted in antiquated modes and themes but energized with bluesy rhythms and rock drive. From Hilton's brilliant but simple guitarpeggio to Eric's growling and howling, to Steel's understated yet spine-tingling cymbal work and Chaz's gutbucket groove, HOTRS takes me into a downward spiral into a flaming cauldron of disaster. Delicious and delirious!

And Alan Price. Good Lord, man! Not a wasted note, perfect intonation, and scarier than anything Jon Lord could dream up in his worst demonic nightmare! Watch him in the classic film clip: https://youtu.be/4-43lLKaqBQ

He's sways and spasms like he's slowly being consumed by a flaming demon. If Burdon was the snarling face and spirit of the band, Price was it's dark and twisted soul. It's because of him, Matthew Fisher and Booker T that I want to buy a Hammond organ and put it next to the Mellotron and Fender Rhodes in the Conservatory of my mind.

"closer to their rowdy Scottish hearts"

Rather their equally rowdy Geordie hearts.

It should be mentioned that The Animals also were the best live act of their time. Check their performance at Wembley 1965 (New Musical Express), where they totally outplayed The Kinks, The Beatles and even The Rolling Stones - in 1965 that is. Only The Who were a match in the two first years of The Animals.