Tracks (UK edition): 1) Mother’s Little Helper; 2) Stupid Girl; 3) Lady Jane; 4) Under My Thumb; 5) Doncha Bother Me; 6) Goin’ Home; 7) Flight 505; 8) High And Dry; 9) Out Of Time; 10) It’s Not Easy; 11) I Am Waiting; 12) Take It Or Leave It; 13) Think; 14) What To Do.

Tracks (US edition): 1) Paint It, Black; 2) Stupid Girl; 3) Lady Jane; 4) Under My Thumb; 5) Doncha Bother Me; 6) Think; 7) Flight 505; 8) High And Dry; 9) It’s Not Easy; 10) I Am Waiting; 11) Goin’ Home.

REVIEW

A long-standing narrative about the Rolling Stones is that the band did not truly find its «right sound» and/or hit its creative peak until Beggars Banquet all the way down at the end of 1968 — finally discovering the perfect way to modernize the old-school blues and rock’n’roll sound to literally create the template for Classic Rock. The only reason, in my mind, why this narrative is so persistent, and why it is so difficult to challenge it (although people have been trying to, more and more, as time goes by and «rockism» is gradually replaced by «poptimism»), is that both Mick Jagger and Keith Richards have so adamantly supported it themselves, over the years. Already on their 1969 tour, their setlists included fairly few pre-‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’ numbers, with the obvious exception of ‘Satisfaction’ and one or two other songs here and there — and while in 1969 this could easily be ascribed to artistic reluctance to fall back on the «golden oldies», so as not to seem irrelevant and outdated in a burgeoning era of pop music creativity, this weird «unofficial ban» on pre-1968 content persisted even unto the decades in which the Stones were no longer that ashamed to be seen as a nostalgia act (one might actually argue that these decades started at least around 1975–76). It was never a total ban — big hits like ‘Paint It Black’ and ‘Let’s Spend The Night Together’ did expectedly escape oblivion, and sometimes the band would even dust off a ‘Route ’66’ or a ‘Heart Of Stone’ — but on the whole, the trend never changed, and, of course, it also kept on being fueled by the Rolling Stone clique, as well as «casual» (rather than «advanced-level») fans of the band, who would keep on selling the image of The Rolling Stones as a sort of legendary prequel to AC/DC for curious neophytes, often leaving said neophytes disappointed.

The main discomfort I’ve always had with this narrative is that Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, to put it very simply, are a couple of musical geniuses — maybe not on the level of Lennon/McCartney, maybe working from a different set of creative parameters, but, in any case, with way more talent to burn than it takes to just produce a dozen albums’ worth of catchy, crunchy, dirty riff-rockers. That talent often found itself stilted — by peer pressure, by drugs, by vanity, by cold commercial calculation — but it was there right from the start, and it did not really begin to seep away until all these factors became multiplied by the most troublesome of them all (old age). Even those recordings that I consider to be real missteps — and hey, nobody’s perfect — still show signs of that talent; and even those that maybe owe a little more to their influences than they should are still infused with the band’s unique personality to the point of fully redeeming themselves.

The most common criticism that is usually addressed at the band’s «pop», or «pop & psychedelic» period of 1966–1967, is that in those years The Rolling Stones were not really being themselves — that they were just blindly following the artistic (and commercial, which just so happened to fortuitously co-align for a short time) trends of those years. The Beatles led the way, the Kinks indicated a less popular, but no less fruitful artistic alternative, Hendrix and Pink Floyd were setting new standards for the psychedelic idiom, and the Stones, with their tongues hanging out, just so happened to lap hungrily at superior competition, knocking out mildly decent, but decidedly second-rate imitations while turning their backs on nurturing their own true talents. Lost in chaos, drugged out and exhausted from their legal problems, they did not really get their heads back on altogether until they braced themselves for ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’ and finally found the light.

Ironically, the same conventional narrative often strengthens and even idealizes the role of Brian Jones in those troubled years, painting him as the short-lived bright shining star along the same self-destructive lines of Syd Barrett — the mini-genius who could turn everything to gold whenever he was properly «in the zone», but paid for this by burning out too fast. At least for Brian on a personal level, nobody ever dares to suggest that he was unable to «find himself» on those 1966–67 records; grudgingly or lovingly, people do acknowledge that he went through a period of tremendous artistic growth, rapidly transforming from his purist-blues «Elmo Lewis» phase into the quintessential mid-Sixties musical hero — «the guy who will try anything once», compensating for lack of technique and professionalism on all those sitars and dulcimers with a genuine feel for the instrument. That said, Brian Jones never managed to grow into a proper songwriter; ultimately, his role on these Stones recordings was the same as that of the other great session players who sat in with the band at the time, from Nicky Hopkins to (later) Ry Cooder and Bobby Keyes. He proved himself capable of latching on to Mick and Keith’s ideas, but, for some reason, incapable of starting up any ideas of his own (and no, it was certainly not due to the Glimmer Twins holding him back or vetoing his contributions in the same way that Lennon and McCartney, for instance, were known to hamper George Harrison’s songwriting ideas — Brian literally couldn’t «write» anything).

Perhaps the Stones’ most glaring deficiency in the Revolver / Pet Sounds / Sgt. Pepper era of revolutionary studio wizardry was the sore lack of a capable producer, be it on the level of a wise, well-trained professional like George Martin or an accidental genius of sonic engineering like Brian Wilson. As instrumental as Andrew Oldham was in creating the Stones’ public image of rock’n’roll’s enfants terribles, and as laudable as were his constant efforts to push Mick and Keith to write more and more original songs, his actual contributions as a «producer» had always been neglectable — and while this might not have been a big deal in 1964, when the rawness of the Stones’ sound propelled it artistically and commercially all by itself, the whole thing backfired in 1966, when the world decided that simply going into the studio and playing your guitars and singing into a tin can no longer sufficed to make a cutting edge artistic statement. Not that the Stones were alone in this — contemporary records even by some of their chief competitors, like the Kinks and the Who, could also definitely use a more advanced level of production — but their reputation of the Beatles’ chief competitors on the same side of the Atlantic inevitably put them to a higher standard of evaluation than everybody else, and with Oldham at the (imaginary) wheel, that reputation was impossible to support in those two crucial years when they most needed it.

This, more than anything else, I think, is why an album like Aftermath feels a bit... «high and dry», to borrow the title of one of its tracks, next to Revolver or Pet Sounds (both of whom it admittedly preceded, but the same problem still persisted all through 1966 and early 1967). At the end of the day, even taking into consideration all of Brian Jones’ slightly «exoticized» contributions to the instrumentation, it is still just an album of pop-rock songs with guitars and vocals. It does not open any portals into mystical alternate dimensions, it does not blow your mind on account of unpredictable and unusual sonic effects or weirdass chord combinations, and, honestly, it does not even rock all that hard, what with the Stones intentionally aiming for a softer, more melodic approach in their songwriting. It certainly lacks that special something to put it right over the top and land it right next to the most important landmarks of 1966. But even with all those reservations, Aftermath is arguably the single most important LP that The Rolling Stones ever released in their career — maybe it was not an album on which they «began finding The Rolling Stones» (as per Keith Richards’ own opinion, this would be Beggars Banquet two years later), but it was definitely the album on which they found The Muse Of Consistent Inspiration, to whom they would remain loyal, steadfast and true for the next six or seven years — before the Muse got so pissed at constantly playing second fiddle to Bianca Jagger and Anita Pallenberg that she started whoring herself out to Gene Simmons in jealous revenge.

A bit ironically, most of the material for both Aftermath and its thematic sequel, Between The Buttons — two of the most «English-sounding» LPs the band ever made — would be recorded at the RCA Studios in Hollywood (and conversely, their most classic «American-sounding» LPs of the late 1960s would all be recorded in London); Aftermath, in particular, was almost completely engineered over the course of two three-day sessions that respectively took place in December 1965 and March 1966, each one flagged by a major single. The first of these somehow never made it onto either Aftermath or any of its LP follow-ups (even the jumbled US mess of Flowers), so it’s kind of suitable to start our analysis from there: after all, what with its release on February 4, 1966, more than two months prior to Aftermath itself, the song announced The Rolling Stones’ competitive entry into 1966, the year that (once again) was to change music forever — and even if it did not manage to secure itself the same landmark-iconic status as ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’ two years later, it did convey the message: the times they were a-changin’, and your good bad boy friends, The Rolling Stones, were happy and willing to bring you some of those changes by their personal self.

The single biggest influence on ‘19th Nervous Breakdown’ is arguably not Bo Diddley, a slight variation on whose ‘Diddley Daddy’ theme opens the song and later recurs in the bridge sections, but rather another B. D. — Bob Dylan, whose own mixture of shamelessly stolen old school rock’n’roll riffage with convoluted numeric titles like ‘Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream’ and acid-dripping character-assasinating lyrics was all the rage in late ’65. In fact, even though putting down arrogant high-class ladies had already become quite the hobby for Jagger and Richards by that time (‘Play With Fire’ is a particularly memorable example), ‘19th Nervous Breakdown’, with its long-winded and exquisitely mocking verse lines ("You’re the kind of person you meet at certain dismal, dull affairs / Center of a crowd, talking much too loud, running up and down the stairs"), sets a whole new standard for them — and, unlike Dylan, Mick Jagger is incapable of clouding his lyrics in too much metaphoric or surrealistic imagery, preferring instead to tell the story as it is (which may be a good thing, because some of his more obvious nonsensical Dylanisms on Between The Buttons and Beggars Banquet would come across as forced second-hand imitations).

Here, before proceeding further, it might be prudent to say a few words about the purported «misogyny» of both this particular song and numerous others that seem to have been particularly prominent in the 1966–67 period (‘Stupid Girl’, ‘Under My Thumb’, ‘Backstreet Girl’, etc.) and certainly come across as shocking or questionable to excessively sensitive «modern audiences». While in his actual relationships with women, all the way from regular girlfriends like Chrissie Shrimpton and Marianne Faithfull to all sorts of one-night stands, Mick Jagger was as far removed from a saint as the average politician is removed from an honest statement, it would be unfair to claim that his lyrics promote a consistently negative portrayal of womankind — even on Aftermath itself, savage putdowns like the ones namechecked above coexist peacefully back-to-back with the chivalrous declarations of ‘Lady Jane’, the desperate longing of ‘I Am Waiting’, and the realistic thinking of "it seems a big failing in a man / to take his girl for granted if he can" (‘It’s Not Easy’). But it is also true, of course, that poking mean fun at the alleged holes in various ladies’ moral character was a particular favorite for Mick in those years — no doubt based on personal experience, to some extent at least.

That said, who exactly does ‘19th Nervous Breakdown’ poke fun at? Some have specifically suggested Shrimpton (and Chrissie herself seemed pretty convinced it was about her), but even if she did have nervous breakdowns, there’s hardly any evidence of her father ever having made a fortune in sealing wax, or of her mother owing a million dollars tax, for that matter. Marianne Faithfull, in her autobiography, is particularly adamant: "The turning point in their relationship had come at Tara Browne’s twenty-first birthday party in 1966, which was held at Luggala, a picturesque estate in Ireland. It was there that Mick and Chrissie took acid together for the first time. The result was apparently disastrous. You can glimpse the nerve-jangling fracture in Mick’s pitiless recital of her crack-up: ‘Nineteenth Nervous Breakdown’. A whole relationship gone haywire is ruthlessly appropriated in that song. He would later do the same to me, by the way!" Only problem with this account: Tara Browne’s 21st birthday party could not have taken place before March 4, 1966, by which time ‘19th Nervous Breakdown’ had been riding up the charts for at least a month already. (Incidentally, Tara Browne would never make it to his 22nd party — it’s the same Tara Browne who perished in a car crash in December of that same year, later to be immortalized in John Lennon’s lyrics for ‘A Day In The Life’). Never trust autobiographies until you cross-check them with other sources of evidence, boys and girls.

Of course, this does not mean that Shrimpton could not have served as partial inspiration for the song, as well as for multiple others — but I think that if we really feel the need to condemn Mick for being an asshole to his girlfriend(s), we should still rather look for evidence of this in his real life, rather than in his artistic processing of it. For better or worse, ‘19th Nervous Breakdown’ is a scathing — and pretty unsympathetic — portrayal of an abstract high-class socialite, spoiled (and traumatized) by her parents and the egotistical social circles in which she had no choice but to become entrapped. Is this «misogynistic»? Well, perhaps only in that Mick could have written an equally scathing song about a male protagonist (following the example of, say, Ray Davies, most of whose own critical targets were men rather than women — which, I guess, still does not make him a «misandrist»), but chose a woman instead — for the simple reason, I think, that Mick Jagger simply liked to spend more time around women than he did around men... and for that, I couldn’t blame him. Males do tend to be boring, unlike the female protagonist of ‘19th Nervous Breakdown’.

A much more serious case could be built not against Mick Jagger analyzing (perfectly realistic and credible) flaws in his female characters, but rather against him building up his own persona as the holier-than-thou potential savior of all these lost sheep: "on our first trip I tried so hard to rearrange your mind", he sings, as if fully convinced that dropping acid is the perfect remedy against old-fashioned patriarchal bourgeois values. Well, that’s what you get for accepting Bob Dylan as your prophet: it would take several more years for the rebellious young men of the mid-Sixties to realize that maybe their amazing skills at making conformist young women of their generation see the light weren’t really all they were chalked up to be. But, once again, excessive self-confidence and arrogance in real life is one thing, and in art is another — I mean, if we believe that Bo Diddley, the musical grandaddy of ‘19th Nervous Breakdown’, is somehow really able to make love to all those pretty women standing in line in an hour’s time, we might as well believe that Mick Jagger is an acceptable teacher for a spoiled young lady on the art of "treating people kind". (Actually, he’s a pretty poor teacher — "but after a while I realized you were disarranging mine" is a bit of a humorous self-slap in the face, too).

Before this turns into an anthropological dissertation, let’s revert back to the musical qualities of ‘19th Nervous Breakdown’. Apart from the ‘Diddley Daddy’ interpolation, its core melody seems almost annoyingly unexceptional, just a basic two-chord bluesy stomp against which Mick spins his defiantly elongated verse lines — a classic Bob Dylan approach if there ever was one. This, however, implies the lyrics should be listened to (and like I said, they’re seriously good lyrics), and it helps set the stage for the main hook, when the little "you’d better stop" pause is followed by Keith’s screechy «brake»-like blast of feedback and then the song slowly gets back into fast gear alongside Mick’s double-tracked "here it comes, here it comes... here it comes your 19th nervous breakdown!" None of this may be sheer genius, but all of this is pretty satisfying musical theater, with the instrumentation telling as much of a story as the lyrics. This, by the way, could not have been aped from Bob Dylan, master of the static groove; it’s much more of a Beatles or Kinks thing that the Stones were now adapting to their own brand of rhythm’n’blues.

Of course, one shouldn’t forget the cherry on top — while the Wyman/Watts rhythm section remains tight and energetic throughout the entire rocker, most people begin paying special attention to Bill only in the coda, when Mick’s gradually fading-out repetitions of the chorus get echoed by a series of «dive-bombs» played by Wyman. This was not the first case when the bassist attempted to steal the limelight (he did have a solid history of eerie zooms and zoops in the band’s early catalog), but probably the first one in which his bass became an integral part of the story, in this case, symbolically evoking the «nervous breakdown» itself. For that matter, I can barely remember if this particular technique had been applied at all in rock’n’roll bass playing — the rapid descending pattern takes its basic cue from surf-rock à la ‘Pipeline’ or ‘Misirlou’, but that would be guitar, not bass playing, and typically used as an introductory gimmick, not a regular flourish within the song itself. Admittedly, The Who’s John Entwistle would use this rumble trick a lot (e.g. in almost any live performance of ‘Summertime Blues’), but that would be after ‘19th Nervous Breakdown’, not before — not to mention that the dive-bomb bass line in ‘Summertime Blues’ is just there for the fun of it, without any particular symbolism.

All in all, ‘19th Nervous Breakdown’ was not the Stones’ greatest song — for one thing, the main melody is too conventional to hail it as a production of compositional genius — but it was a massive artistic breakthrough for them on several levels, starting with the lyrics (Mick Jagger finally earns the right to social criticism) and ending with the ability to absorb contemporary influences without sounding like second-rate imitators, due to each individual band member’s touch on their respective instruments. Much more than the fuzzy ‘Satisfaction’, it feels like the starting blueprint for almost everything the band would be doing in their Aftermath / Between The Buttons period.

Skipping, for the time being, all the other great songs they recorded for Aftermath during the same session, let us jump right across into early March of 1966, when, instead of resting on the laurels of ‘19th Nervous Breakdown’ for a while (#2 in both the US and the UK), the band returned to the same RCA Studios to lay down their next single — which, although it also depicted a nervous breakdown of sorts, ended up being something completely different. Something, in fact, that they probably could not see themselves doing at any particular time earlier than the spring of 1966, I might add.

It is said that ‘Paint It Black’ started life as a slow, meandering, and generally unimpressive ballad in the studio, until Bill Wyman started hammering out an additional bass riff on the pedals of a Hammond organ, speeding up the tempo (in later years, he would occasionally grumble about not receiving songwriting credits for the idea). Whether it was to Bill’s credit that the song received its Near Eastern flavor, or it was conceived that way from the start, is also not quite clear, but one does indeed regularly hear, in cojunction with it, either the word «Jewish» (as in, «this sounds like a Jewish wedding dance tune») or «Turkish» (as in, «this was clearly influenced by Erkin Koray’s ‘Bir Eylül Akșamı (One September Evening)’» — which is not completely excluded, since the song, recorded by the Turkish rock’n’roll pioneer in 1962, did officially come out in 1966; I have no idea, though, how Mick and Keith could have heard it, and anyway, the resemblance is more general than concerning specific chord sequences). As a final touch, Brian Jones throws in a sitar part, which makes the song even more «exotic» without, however, making it sound more Indian (let’s just call it a setar instead and move a little to the West, closer to the Jewish weddings and the Turkish bars).

If ‘19th Nervous Breakdown’ taught the Stones to excel lyrically and theatrically, then ‘Paint It Black’ moved them out of their traditional comfort zone — the blues — and introduced them to a whole new world of musical influences, which they would gleefully explore for the next two years before returning to the blues (but already on a whole new level of overall experience). Now this might seem surprising, but I don’t actually think that ‘Paint It Black’ is a perfect song: I think that, in their focused attempt to write a particularly dark and gloomy tune — perhaps inspired by something like the Yardbirds’ ‘Still I’m Sad’, which is probably the likeliest candidate for the most utterly hopeless song of 1965 — Mick and Keith went a little overboard with the theatrical flavor: Mick «over-writes» and over-sings lines like "I look inside myself and see my heart is black", somewhat similar, incidentally, to the average overwrought, over-emoting Eastern balladeer, and the song never reaches the gruesomely gritty heights of, say, a ‘Gimme Shelter’ or a ‘Sister Morphine’ — you don’t really get chills from it, you just tap your foot along to the rhythm and hum in unison with Mick. But it’s OK. They were learning, the night was still young, and a bit of overwrought simplicity («if you want to write a gloomy song, don’t forget the word ‘black’!») was certainly permissible at this point.

What actually elevates ‘Paint It Black’ from a mere imitation of a Near Eastern drone, I think, is its constant fluctuation between the melancholic echoing thump-thump-thump of the verse melody and the livelier, more familiar and «rock-and-rollish» bridge — the chord change between "I see a red door and I want it painted black" and "I see the girls walk by dressed in their summer clothes". In those moments, the slightly fake-ish theatrical gloominess of the verse — a sentiment that might feel natural to Jim Morrison or Ian Curtis, perhaps, but hardly ever to Michael Philip Jagger — smoothly transitions into fussy, barely controlled anger, and this is paralleled by the melodic lines becoming more Western than Eastern: not a «window into the light», as it happens, for instance, in the bridge sections of ‘Comfortably Numb’, but rather a «window into the more familiar brand of darkness», before the deep dark drone monopolizes time and space over the lengthy coda, which Wyman uses once again, by the way, to show off the demonic potential of his instrument.

As much as I am willing to admire this combination of elements, or the tremendous importance of ‘Paint It Black’ to the Stones’ reputation — it was an early and a 100% successful stake in the great «art-pop» race of 1966–1967 — I do believe, also, that out of all the songs on either the UK or the US editions of Aftermath, it is the one that is the most «artificial», almost feeling as if it were written as part of a specific challenge to write an exclusive contemporary pop-art-lieder. Perhaps it is not entirely coincidental that, after performing it for a while on their tours in early 1966 (but tellingly failing to include it on the Got Live! LP), the Stones permanently retired it from the setlist — despite it becoming their most commercially successful single up to that point — and did not return to it until the 1989 Steel Wheels tour, which, all by itself, featured their most openly «theatrical», self-mythologizing spectacle ever. Who knows? maybe Mick could have an inkling himself that he’d finally earned some natural right to the song’s grossly over-exaggerated darkness by that time. In any case, I am oddly glad that it elicits such a complex reaction out of me — and besides, some of the best «fake» Stones material is the kind of stuff I’d still take over much of late-period «earnest Stones» material any time of day.

One thing at least was obvious: by early 1966, The Rolling Stones had turned into an efficient, unstoppable hit machine, despite the relative «nastiness» of their music — which they could easily compensate for by throwing in one unbeatable pop hook after another (and since teenagers still remained as the principal absorbers of 7-inch records, the «nastiness» itself did not matter all that much). Even the extreme verbosity of ‘19th Nervous Breakdown’, with the unbeatable pop hook taking plenty of time to arrive at, did not prevent it from going all the way to #2; and even the puffed-up dark vibe of ‘Paint It Black’ did not scare away the band’s audiences, but instead further enthralled them with the classic image of Brian Jones as the mystical-romantic hero, He Of The Blonde Hair, White Kaftan, And Poorly Tuned Sitar. They’d finally done it: they turned into self-sufficient, professional, if, perhaps, not yet fully confident, songwriters of their own material, and, more importantly, their craft was being critically and commercially vindicated on a level second only to the Beatles, while on a «socially relevant» level of music-making it might have been perceived as superior to the Beatles, whose own social commentary was still rare and usually framed in light-joke mode (‘Drive My Car’) or as subtle, barely detectable sarcasm (‘Norwegian Wood’).

The natural thing to do now was make one last step and prove to the world that The Rolling Stones could be the masters of the LP domain as well; as of early 1966, they did not yet have a single full album under their belts on which their own songs would outnumber the covers, let alone be the sole material of it. Here, too, Andrew Oldham must be commended, as he kept tirelessly pushing Mick and Keith to scale this last height — probably the best thing he ever did for the boys, although it was also Oldham’s fault that the record would be delayed for more than a month for insisting on the title Could You Walk On The Water? that Decca refused to endorse — leaving the year’s biggest Christianity-related scandal to the Beatles. Not that I blame the record industry: Oldham’s proposed title (which he planned to accompany with a photo of the band standing atop a California water reservoir!) is silly and would in no way be relatable to the album’s content. Not that Aftermath is a particularly strong alternative — aftermath of what? feels more like a suitable title for a bunch of archival outtakes after a band breaking up — but at least it does not reek of unnecessary pretentiousness, and is easy enough to memorize.

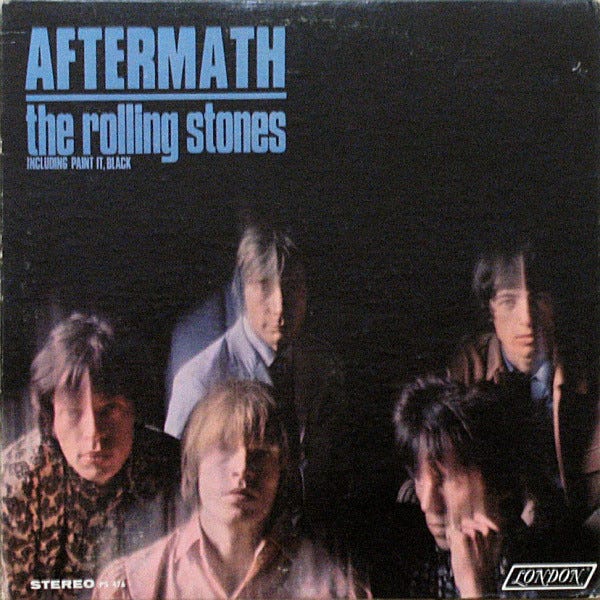

The biggest problem with Aftermath as an LP is the continuing discrepancy between US and UK editions, which, by 1966, had become a real nuisance — as long as the Stones mainly relied on covers for their LPs, juggling the songs around could be excused, but now that they were packing whole sides of vinyl with their own creations, cutting and swapping at will no longer felt justifiable. The original UK release had 14 tracks — one of them clocking in at a whoppin’ 11:18, with the entire album running over fifty minutes in length, quite a record even for Britain and something completely unheard of for a pop album in the US, unless we’re talking Bob Dylan (whose own 50-minute-long or so albums on Columbia were basically carry-overs from the folk label tradition of anti-commercialism). For the American market, this would not do, so, after a delay of two more months, the US Aftermath chopped off four of the tracks (three of them would only be introduced to American audiences a year later on Flowers, and one, ‘What To Do’, disappeared forever), over-compensated with the inclusion of ‘Paint It Black’, and slightly reshuffled the rest. Only one good thing came out of it, I think: I have always felt that the mega-monster jam of ‘Goin’ Home’ was much more appropriate as the last track on the album (in the US version) than merely closing off Side A (in the UK version).

Granted, the dark fury of ‘Paint It Black’ is a perfect opening for any Stones record, right up there with ‘Sympathy For The Devil’ or ‘Gimme Shelter’. But in placing it first at the expense of its UK counterpart, American Decca had inadvertently ruined the quirky conceptuality of the opening sequence — as the Rolling Stones come out with a small «portrait gallery» of four different types of four very different women: ‘Mother’s Little Helper’, ‘Stupid Girl’, ‘Lady Jane’, and ‘Under My Thumb’ each explore their own brand of femininity under their own specific angle. If anything, this sequence alone should have warranted the band naming the LP with a quotation from one of their earlier songs — There’s Been So Many Girls That I’ve Known would have made a much cooler title than Aftermath or that earlier «sacrilegious» idea from Oldham, though something tells me Decca might not have been too hot about this idea, either. (It’s one thing to put down traditional family values inside your songs, and quite another one to boast about it on the front sleeve.) And somehow I even feel pretty sure that Mick and Keith really have known all those lasses all along — and not even on a purely sexual level.

Each of these four songs is its own little gem in its own special way, and each illustrates its own attitude to its protagonist, running the gamut from bitter empathy (‘Mother’s Little Helper’) to infatuated hatred (‘Stupid Girl’) to oddly courteous amorousness (‘Lady Jane’) to gleefully dominant revenge (‘Under My Thumb’) — each of these emotions correlated with a specific instrument coloring the song (in the same order: 12-string electric sitar-like slide, Hammond organ, dulcimer, and marimba). No sequence like this had previously existed in popular music, where songs typically rested on exploring the relationship between the singer and his heroine; here, though, Jagger is either a ghost observer (as on ‘Helper’), a passive admirer (‘Lady Jane’), or a focused painter of the object of his obsession (the other two songs). In this respect, it might be argued that this here was one lesson the Beatles could have taken home from the Stones themselves — their own «portrait galleries» would not really begin to properly take shape until Sgt. Pepper.

In its own way, ‘Mother’s Little Helper’ is no less tragic an album opener than ‘Paint It Black’ — and grounded in a far more brutal and unforgiving kind of reality at that. Musically and «socially», this is the Rolling Stones reacting to the Kinks — the music hall-style rhythm seems inspired by the likes of ‘A Well Respected Man’ — but there is an extra bluesy toughness here that could only come from the Stones, while Mick’s lyrics are unquestionably on par with Ray Davies’ best efforts: "She goes running for the shelter / Of her mother’s little helper" and "the pursuit of happiness just seems a bore" are downright miraculous lines, and the entire description of a busy housewife’s traumatic existence has no precedent. The song’s motto, which they actually take care to extract from the bridge and slap onto the opening bars, is "what a drag it is getting old" — but is it sung with humanistic pity or with grinning scorn? it’s a bit hard to say with Mick Jagger, whose singing voice is physically incapable of conjuring classic «pity» vibes (unlike, say, Paul McCartney with ‘For No One’ or ‘Another Day’), but I would say that if there’s anger and sarcasm directed at something here, the something in question is not the poor woman of the house herself, but rather the absurd social setting which condemns her to a pill-dependent existence.

The melody here is sheer genius. Each verse starts and ends in the key of E minor, the same merry fellow that would later give us such life-affirming jolly-rides as ‘Riders On The Storm’, ‘Come As You Are’, and ‘Enter Sandman’, and begins with a slice of depressing reality ("kids are different today", "things are different today", "men just aren’t the same today", "life’s just much too hard today"), then it gets «pushed up» into brighter, busier, fussier territory with a bunch of major chords — that’s poor mother trying to cope with her daily routine — and then down it goes again, back into the same E minor with a sense of ultimately inescapable finality. When the last verse arrives with "and if you take more of those, you will get an overdose — no more running for the shelter of her mother’s little helper", it’s not even all that shocking, we probably were expecting something like that all along. E minor, you know. The key of death ever since Mozart’s Violin Sonata No. 21, there’s just no getting away from it. And how about that repetitive quasi-sitar figure (actually played bottleneck-style on a 12-string electric guitar)? That kind of flourish is actually what I miss the most on similar Kinks songs like the aforementioned ‘Well Respected Man’, or ‘Dedicated Follower Of Fashion’, both of which establish a great general groove but then decide to restrict all the dynamic developments within the songs to the lyrical delivery. It’s like a five-second little dirge for mother, a weirdass funeral bell ringing in between each verse: creepy and inescapable.

Unlike ‘Paint It Black’, which did go through periods of both stage acceptance and ostracism, ‘Mother’s Little Helper’ seems to have never been played live by the Stones — perhaps there is some sort of mystical grudge that Mick himself holds against some of his most socially biting songs from that period, or maybe he fears that his audiences consist of too many valium-poppin’ middle-aged mothers to risk alienating them altogether. But the level of greatness of a Rolling Stones song should never, ever be determined by whether Mick and Keith love taking it out on stage or not — rather it should be determined by how certain we are of its message, and apparently in this case we aren’t: ‘Mother’s Little Helper’ has been described as anything and everything from hateful/misogynistic to caring/compassionate, which, in my book at least, is a pretty solid criterion for great art.

Next to it, ‘Stupid Girl’ is probably not great art, and the neighborhood makes the song look somewhat snotty and silly in the context of the far more serious ‘Helper’. But it is still a fine example of how the Stones, at the time, were capable of taking a solid rock basis — the choppy, chuggin’ rhythm guitar is basically the same that Keith would later borrow for his slowed-down, decadent take on Chuck Berry’s ‘Little Queenie’ — and building an enjoyable pop experience on top of it, exemplified here by Mick’s prolonged melodic emphasis on the main vocal hook ("look at that stupid... GI-I-I-I-IRL!") which I always mentally associate with sticking your tongue out at the poor derided heroine, as far as it can go. Sound-wise, though, the song really belongs to Charlie (whose relentless, monotonous pounding really drives home the stupid! idea) and Ian Stewart on the Hammond organ — somehow his tone on that thing manages to take some of the nasty edge off the lyrics and give the entire song a light-hearted, playful attitude.

Which it definitely needs, as this is easily the meanest of all four portraits (so viciously mean, in fact, that it even worried poor Elvis Costello into writing an apologetic follow-up a decade later, in the form of ‘This Year’s Girl’). We still don’t know exactly who it was that pissed Mick off to that extent (could be absolutely anybody on a bad day, even Chrissie Shrimpton herself, with her false eyelashes and stuff), but, in all honesty, the actual portrait is perfectly realistic — most of us have probably encountered this particular type of «stupid girl» in our lives, even if the actual sex does not matter (plenty of «stupid boys» hold up precisely the same standards of stupidity). What I actually find hilarious is that not once in the song does Mick ever hint at the idea of a break-up — it’s clear that the «stupid girl» in question is the singer’s girlfriend, whose way of life he is desperately trying to change ("I’ve tried and tried, but it never really works out"), yet despite all the disgust and aversion, he is still clearly infatuated with the character; the entire thing plays out like a soul-alleviating rant you let out to yourself locked in a bathroom, banging your head against the mirror, after spending a couple hours watching your posh girlfriend embarrass herself (and you) again at the latest frat party.

Regardless of any implications for your own moral character, though, ‘Stupid Girl’ is probably the weakest link in the portrait gallery, as its melody is the most «conservative» of the bunch (it really hearkens back to all those early blues jams like ‘2120 South Michigan Avenue’). In sharp contrast, ‘Lady Jane’ follows it as the most radical departure from the proverbial «Stones sound» as they ever had up to that point — a tender, gallant «Elizabethan» ballad, carried forward by Keith’s delicate acoustic guitar, Brian’s lead riff struck out on a dulcimer, and, eventually, Jack Nitzsche’s harpsichord. The closest they ever got to this kind of sound was ‘Play With Fire’ earlier in 1965 (acoustic and harpsichord again), but that was a decidedly modern song; ‘Lady Jane’ — at least, not until you start getting into the lyrics with a microscope — appears out of nowhere in the form of an almost literal cosplay party at the Tudors’ dinner table.

Again, it is worth noting that nothing of the kind existed in the typical repertoire of a UK pop/rock band at the time. Folk revivalists were, of course, free to roam around that territory, but «baroque-rock» with Renaissance flavors did not even begin yet to properly coalesce. The Left Banke, The Moody Blues, The Amazing Blondel, Renaissance (the band) — all of those beautiful people, one way or another, owe a little something to ‘Lady Jane’ and that slightly clumsy, amateurish, but distinctively adorable Brian Jones dulcimer riff. That this kind of sound was actually introduced to the popular ear by the Rolling Stones — that same quintessential «dirty blues-rock» band, locked into a singular image in the conventional mindset — is a fact just as astonishing as realizing, for instance, that ‘You Really Got Me’ and ‘Waterloo Sunset’ were conceived and written by the exact same person.

It’s a pretty «homebrewn», dilettantish kind of Tudor music, of course. Even the dulcimer itself, if we’re going to be precise, is not the kind of classical hammered dulcimer that was common in Western music since the Middle Ages, but rather the strummed Appalachian dulcimer from the early 1900s’ America — Henry VIIIth never got to hear that one at his dinner table. But it’s not the technical detail that counts, it’s the heart and soul, right? Well then let’s look at those lyrics more closely. (I) Verse/chorus 1: The singer pledges his troth to the mysterious «Lady Jane» in a traditional courteous gesture. (II) Verse/chorus 2: The singer renounces the equally mysterious «Lady Anne», rejecting her affection for a lifetime of eternity to «Lady Jane». (III) Verse/chorus 3: The most confusing of the lot, but the likeliest interpretation is — ‘Marie’ is probably Lady Anne’s maid with whom the singer has been getting it on the whole time, but "her station’s right my love, life is secure with Lady Jane", meaning that the optimal mode of existence is a calculated marriage with Lady Jane while continuing to bone her rival’s chambermaid on a regular basis. On second thought, isn’t that kind of behavior precisely something we’d be expecting of a Mick Jagger transplanted back into the 16th century? Not that it ain’t a kind of behavior fit for an actual king, most of whom built up their relationships with the ladies along similar lines.

The irony, then, is that while on the surface ‘Lady Jane’ might seem like one of the most «anti-Stones» songs in the Stones’ catalog, even a slightly more attentive look at the lyrics can shatter that deceptive impression — just do not let Mick Jagger, the sly one, lull your spirit with the first verse and make you completely let down your guard by the time Jack Nitzsche’s beautiful harpsichord break comes along. (A similar contrast between the delicate beauty of the melody and the sordid underbelly of the lyrics would later be teased on ‘Backstreet Girl’). Taking in the idea that the lyrical hero’s motives may not be, umm, exactly pure also makes it much easier to tolerate Jagger’s somewhat stiff vocal delivery. His range and technique could never be suitable for a proper courteous Renaissance romance. But that ain’t really ‘Lady Jane’ — what ‘Lady Jane’ is is a parade of silent fantasy stereotypes, fully and exhaustively defined by their social roles and nothing else: the aristocratic lady, the aristocratic lady’s less influential rival, the aristocratic lady’s less influential rival’s adulterous chambermaid — and their respective male counterpart, acting in precise accordance with the unwritten codified standards of the time (marry the rich one, eschew the poor one, fuck the one with the biggest tits). How else is he going to sing it if not strictly following the stated protocol? This is not a serenade, it’s an official statement of intention.

And now, back from the perverse medieval fantasy and into the modern... oh but wait a minute. The odd thing about ‘Under My Thumb’ is that most of its usual detractors, ever since the feminist backlash already back in the 1960s and even more so in our present ultra-sensitive times, tend to take the song very, very seriously. This, they say or think, is the apex of Mick Jagger, the woman-hater: "a squirming dog who’s just had her day", "the sweetest pet in the world" — a modern-day setting for The Taming Of The Shrew, the quintessential male chauvinist statement of patriarchal dominance. Promoting gruesome and despicable stereotypes, and, to make matters even worse, doing that in the catchiest way possible. There have been fairly complex attempts at refuting that view, such as the stance taken by the oddly «anti-feminist feminist» Camille Paglia in her essay on the matter, but I, personally, would like to keep this as simple as possible.

And the simple picture is as follows: I seriously doubt that there has ever, even for one day, been an actual real woman in Mick Jagger’s life who has been "under his thumb", or about whom he could really brag that "it’s down to me, the way she talks when she’s spoken to". There have certainly been women whom he’d treated cruelly and unfairly — lots of these, in fact — but there have been no women whose independent spirits he’d somehow broken down into submission (and, most certainly, there were no such women for him back in 1966). What this means is that ‘Under My Thumb’ is really a naughty fantasy, far less realistic, in fact, than the crude resurrection of medieval mentality in ‘Lady Jane’. It’s not a statement of fact or even a serious declaration of intentions for the future — it’s a horny teenage power fantasy that, I’d wager, many of us go through at one point in time or another. That haughty gorgeous bitch at school brushed you off when you tried to make a clumsy compliment? well, don’t tell me you never buried your head into your pillow late at night, trying to find consolation in perverse fantasies of what you’d like to do to that chick if you had the magic power.

That is precisely what ‘Under My Thumb’ feels like, in all its aspects — a midnight-hour pillow-time power-fantasy. She hurt me, she pushed me around, but now a kind old wizard gave me a magic potion and poof, she’s my obedient little slave from now to eternity. Even the actual music has a midnight feel to it. Hear Charlie do this quiet knock-knock-knock tap to start things up, after which the main melody is given over to Brian Jones’ marimba — one of the quietest, most «nocturnal» instruments there is, as if the musicians and the singer don’t want to wake anybody else in the house while they’re cooking up this imaginary power trip. In between the verses (and then in the lengthy coda), Mick is not so much shouting as emotionally whispering his ad libs — "say it’s alright", "ain’t it the truth babe", "feels alright", "take it eeeeaaasy babe..." — fantasizing about himself as The Dominator. It can be construed as gross, yes, or a tad creepy (in fact, the atmosphere here is a direct predecessor to ‘Midnight Rambler’, by which time the mean horny teenager had mutated into a sociopathic murderous monster), but to a stable mind it should feel more hilarious than threatening.

They did take this one out on the road — ironically, it was to this song, rather than ‘Sympathy For The Devil’, that Hell’s Angels killed poor Meredith Hunter at Altamont on December 6, 1969 — but stripped of its hypnotic interplay between the marimbas and Keith’s fuzz bass part, ‘Under My Thumb’ would quickly lose its midnight fantasy aura; when they used it as the rousing opening number on their first true big stadium tour in 1981–82, for instance, it took on the guise of a genuine statement of triumph and dominance — not so much over some unhappy girl as over the Rolling Stones’ fanbase in general, which is probably not nearly as interesting as the original intention. Well, I guess without Brian around, there was little point in lugging around a marimba anyway, and the main riff does sound pretty kick-ass when beaten out by Keith on his chunky Telecaster — and besides, nobody gives a shit about the lyrics in the context of an insane stadium frenzy. But nothing really replaces the seductive intimacy of the original studio recording, or the hypnotic-psychedelic effect of the insistent marimba pulse in one nerve channel and the dangling fuzz bass in another. I’m sure The Velvet Underground would have appreciated this.

Now don’t get me wrong: everything that’s been said above is not some sort of mental game called "let’s get bad boy Mick Jagger off the hook and clear our own conscience" — Mick Jagger is a bad boy, and these songs are certainly not innocent little butterflies calling for compassion and understanding. They are beatings, and pretty savage ones — but also intelligent and reasonable, as well as humorous and hyperbolic. Pretty much the same kinds of beatings that Ray Davies was delivering to people right and left — except, unlike Mick, Ray mostly targeted men, but, like I said, that’s most likely the result of Mick preferring the constant company of ladies rather than gentlemen. And with that precious «bad boy image» that he still had to support, well, it wouldn’t have been hard to predict in which particular directions his own songwriting would skedaddle once he’d finally put a finger on it. My advice — take it eeeeaaasy and enjoy the fantasies with the appropriate humor.

Both the US and the UK editions of Aftermath all cram the hit-laden «portrait gallery» at the beginning of the album, so once the marimba fury of ‘Under My Thumb’ has finally died down, the record no longer stuns you; instead, it settles into a fairly even, modestly adventurous rhythm of competent songwriting, without any more big instrumental surprises and, in terms of lyrical content, focusing more on the singer’s feelings and trials rather than on crude psychoanalysis of his fair sex acquaintances. They are still good songs, though: I think the only one that I do not care at all about is ‘What To Do’, which feels like a half-hearted attempt to cross country-western with the Beach Boys (note the pow-pow-pow vocal harmonies that come straight out of ‘Help Me Rhonda’) and belongs with similar tentative attempts to gain songwriting confidence from 1964–65. In all honesty, I cannot blame American Decca for «losing» the song altogether.

Everything else is good, though. We’ll leave off comments on ‘Out Of Time’ and ‘Take It Or Leave It’ until the review of Flowers, so as to save at least a little space; of the remaining six three-minute pop songs, two veer off into bitter-humorous territory (‘Flight 505’, ‘High And Dry’), two more return to the subject of the difficulty of maintaining a long-term relationship (‘Think’, ‘It’s Not Easy’), one deals with the everyday problem of being a Rolling Stone (‘Doncha Bother Me’), and one more dives into the mystery waters of, well, let’s call it abstract romantic yearning (‘I Am Waiting’). The only collective flaw of these good-not-great songs is the one I already mentioned — lack of a truly creative, involved producer means that, to a certain extent, they all sound alike, reflecting a single-minded sonic style: the lightly blues-pop riffage, the fuzz bass, the nasal vocal tone, the echoey resonance, the trusty rhythm section of Bill and Charlie that excels on every track but feels like a couple of loyal henchmen at Mick and Keith’s beck-and-call. Then, of course, there’s the little blessing-and-curse that Mick and Keith are commonly working as a real team, without defining their individual styles. Nothing like the sharp contrast of the ‘Taxman’ – ‘Eleanor Rigby’ – ‘I’m Only Sleeping’ opening section on Revolver can be found here, reflecting three completely different aspects of three distinct personalities. The Rolling Stones simply did not pack that sort of amount of raw talent — they’d probably have to merge with The Kinks or The Who to catch up.

Even so, when each of these songs is taken on its own merits — sometimes it actually helps to listen to just one, rather than sitting through the entire album in one go — it is easy enough to understand that each one does have merits a-plenty. Take ‘Doncha Bother Me’, for instance, which is essentially a generic 12-bar blues with the exact same core melody as ‘The Under Assistant West Coast Promotion Man’ from the previous year; but they manage to conceal that fact by pinning the tune to a «suspended» Elmore James-style slide riff, repeated over and over again like some sort of swinging pendulum with a Cheshire cat grin on top — meanwhile, the lyrics resonate even stronger in this day and age: "I said oh no, doncha copy me no more / Well, the lines around my eyes are protected by a copyright law". It’s a little surprising that Mick would seem to be bothered so much by third-rate Stones imitators, but I guess you’d really have to transport yourself back in time and into the world of "all the clubs and the bars and the little red cars" to get what exactly was bothering him about the scene. The important thing is, they know they’re doing a generic 12-bar blues here and they are looking for an interesting way to make it sound different, from a rhythmic, instrumental, and lyrical perspective. Maybe they’re not doing a very fine job of it, but they’re learning how to do it.

I am not a big fan of ‘Think’ either (though the "think, think, think about it baby" chorus is sufficiently catchy), and I am not even entirely sure of what it is that Mick accuses his partner of this time ("tell me whose fault was that, babe" — whose fault was what exactly?), but the dynamic build of the song («lecturing» verse — quiet pleading bridge — all-out kick-ass chorus) is miles ahead of most of Mick and Keith’s «structural» efforts from a year or so ago, and shows that even when doing rather obvious filler-type material, they were giving it plenty of honest thought. On the other hand, ‘It’s Not Easy’, probably conceived along the same lines as ‘Think’, always felt like a minor hidden gem to me: the fuzz bass part keeps pumping like a beast, and there’s something weirdly mystical and even threatening about the call-and-response vocals of "and it’s... haaaaard... – it’s not easy!" that always stops me in my tracks when I’m listening. It’s also reassuring proof that, even after all of Mick’s difficulties with finding the perfect female companion to suit all his sexual, aesthetic, and ethical preferences, he is still acknowledging that even an imperfect female companion is still better than none at all: "there’s no place where you can call home / got me running like a cat in a thunderstorm". Well... that’s what you get for complaining about the way she powders her nose, Mr. Jagger. (I’m actually entertaining amusing thoughts about a single that would have the aggression of ‘Stupid Girl’ as Side A and the retribution of ‘It’s Not Easy’ as Side B).

On the humorous side of things, ‘High And Dry’ is a fine enough attempt to emulate some sort of traditional English folk dance (definitely not any American influences here, as much as some people are tempted to throw in references to country-western; amusingly, you can hear much the same whimsical melody three years later whistled by John Lennon in the coda section of ‘Two Of Us’), on top of which Mick spins a twisted double-crossing tale of being conned by a rich girl whom he was trying to milk for money ("it’s lucky that I didn’t have any love towards her / next time I’ll make sure that the girl will be much poorer"). It’s a pretty damn intelligent piece of clowning, and also nicely self-deflating in that, for once, we get not a holier-than-thou protagonist, but a cocky little idiot punished for excessive self-confidence. It’s musically unique and it has great interaction going on between harmonica (I assume that’s Brian, rather than Mick) and Charlie’s non-stop cymbal hiss (genius move for the drummer that gives the song its «rustic» feel).

Then there’s ‘Flight 505’, which is... well, nothing, really, but a straight example of mid-Sixties Stones in all their rock’n’roll band glory. Set a groove, lock in, and don’t let go and don’t change things too much until the very end — with Charlie reprising his recurrent eighth-note fill tricks from ‘Get Off Of My Cloud’ and that fuzz bass swooping down from the sky and just as quickly retiring to introduce and emphasize the closing line of each verse. As a pure instrumental jam, ‘Flight 505’ would have been impressive enough (note that they don’t even do all that much extra work during the instrumental section, rightfully believing that the tight groove is perfectly enough to do the job on its own), but Mick uses it as a backdrop for a funny cynical tale on the imminent dangers of fiddling with your own destiny, as well as providing the perfect personal anthem for aerophobes worldwide. (Occasional speculations about the song having something to do with Buddy Holly’s plane crash are entirely due to the psychological association of «rock musicians writing a song about a plane crash»; it does, however, have much to do with fear of flying, which was a pretty common thing back then for rock musicians, given that they are also human beings and all, well, at least to a certain extent).

An intelligent dark joke, coupled with marvelously well-coordinated playing — and on top of that, Ian Stewart opens the song with twenty seconds of the most symphonic-sounding barrelhouse boogie piano ever, as if gracing the song with the status of an epic ballad that deserves its own triumphant opening. (And if you give it your full attention, you’ll note that he throws in one bar of the ‘Satisfaction’ riff right before the band takes over — the universal spice that never fails!). It might actually be Ian Stewart’s crowning moment of solo glory, because, come to think of it, you very rarely, if ever, hear the guy raise his own instrumental voice: Nicky Hopkins would get plenty of solo representation on Stones’ records, but Stewart always sat it out in the shade, and this might just be his single solo bit on a Stones record before they put that very brief jingle as an unnamed track in his honor at the end of Dirty Work to commemorate his passing.

Hiding somewhere in between all these solid, if unexceptional, pop-rockers is what might be the strangest number on the entire record, very rarely discussed in a general Stones context but always raising an eyebrow if somebody actually stumbles upon this «deep cut»: ‘I Am Waiting’. Its shy, gentle, kind of a «don’t-mind-me-I’m-just-pitter’-patterin’-over-here» acoustic melody is not thrown directly in your face, as it is with ‘Lady Jane’, but kept hovering in the corner — I honestly have no idea what the chief inspirations here might be, but it does give off a bit of a Simon & Garfunkel vibe (is it just a coincidence that ‘Homeward Bound’ was released less than two months prior to its recording?). After song after song after song in which the protagonist’s cocky confidence came off harder than a rock, ‘I Am Waiting’ suddenly gives us insight into the delicately vulnerable corner of his heart, revealing vague hopes and fears without any excessive look-my-poor-heart-bleeds-for-you showing-off.

There is no consensus among Stones fans and scholars on what these hopes and fears properly relate to. Naturally, "I am waiting, waiting for someone to come out of somewhere" would suggest that the song symbolizes that eternal yearning for a perfect union — one that cannot be properly substituted by a stupid girl, a Lady Jane, or even a squirming dog that’s just had her day — but as the unexpectedly paranoid blues-rocky bridges start piling up, new lyrics begin to directly contradict that interpretation, so much so that I am even inclined to believe Stones’ biographer Martin Elliott that the song is really about death: "See it come along and don’t know where it’s from... Slow or fast, end at last... Like a withered stone, fears will pierce your bones...". Maybe, in the end, it’s about both — or, rather, even more simply, it’s just a song about waiting, be it for something good in your life or for its inevitable end. If so, ‘I Am Waiting’ is truly an artistic masterpiece — maybe an accidental artistic masterpiece — on a scale that no other pop band had attempted as of yet, and a grand precursor to a large chunk of the entire art-rock movement.

The major / minor contrast between verse and bridge is not an uncommon thing on Aftermath — it began already with ‘Stupid Girl’, marking the opposition between angry nagging and pained desperation — but it works finest of all on ‘I Am Waiting’, because the verse melody is not angry or fussy, but gallant and reticent, as if the actual process of "waiting" is a courtly, respectful ritual for the obedient and understanding singer. Then, however, something snaps, and all of those fears and worries he’d been blocking out of his mind suddenly come through... then somebody gives him one of those little yellow pills and it’s back to calmly accepting one’s fortune. Think long enough about these transitions and you might just be onto something terrifying. Also, there’s more of the dulcimer. The instrument of exquisitely lascivious adultery, such as it was on ‘Lady Jane’, may be turning into the tool of the Grim Reaper here — so think twice, listener, before you start drooling with admiration at the use of period instruments in the baroque-pop revolution!

(On a side note, while the relative obscurity of ‘I Am Waiting’ prevented it from being covered too often, I do strongly recommend Lindsey Buckingham’s revival of the tune on his Under The Skin album from 2006 — it does feel like the perfect set of vibes to connect with his own restless spirit, though I am a little aggravated that he did not play out the sharpness of the contrast between verse and bridge as strongly as the Stones do it themselves. But he did acknowledge the depth and mystery of the song, and that’s good enough for me.)

Had I been in charge of the original UK edition of the album, I would not mind simply throwing out the fillerish ‘What To Do’ and moving ‘I Am Waiting’ to the closing position — so distinct is it from everything else on the album, that it would have been a brilliant move to close it off on this moment of wavering, disturbing self-introspection; it would be nearly as perfect as, say, having ‘Moonlight Mile’ to wind down the fury and hellfires of Sticky Fingers. In a way, the US edition went ahead and nearly did that, as ‘I Am Waiting’ is the last «proper» track on that album. Normal people are expected to just take a look at the running length of the last de-facto track and run away in terror, right?

Well... many still do, as ‘Goin’ Home’, in all of its 11 minutes and 12 seconds glory, is definitely not meant for everybody, not even for everybody who craves compositions of such length from all sorts of respectable art- and prog-rock bands. Of course, the Stones were not the first to crash the 10-minute barrier on a pop record: Dylan had already done this with ‘Desolation Row’ the previous year. (Interestingly, the running time of ‘Desolation Row’ is 11:20, while ‘Goin’ Home’ is just a tiny bit shorter — 11:13 to 11:18, depending on groove cut-offs; however, the original back sleeves always indicate a slightly incorrect running length of 11:35 — this could have been a technical error or a tape discrepancy, but it’s quite possible that somebody intentionally introduced this slight error so as to simply make an «up yours, Bob!» statement.)

But the Dylan precedent would not be entirely honest, because, in a way, ‘Desolation Row’ was merely a natural extension of his craft at creating lengthy ballads that went all the way back to Freewheelin’ (and were themselves inherited from the folk tradition) — plus, it was actually a long song, with multiple lengthy verses and a boatload of written lyrics. ‘Goin’ Home’, meanwhile, only remains an actual «song» for about three minutes; from then on, it becomes an improvised jam, with Jagger ad-libbing ad infinitum — something that was being done by various bands at the time, but only during their live shows. The very idea of simply wasting eight or ten minutes of precious vinyl space on spontaneous messing around in the studio was so preposterous that nobody entertained it. In fact, I’m pretty sure that the Stones themselves never guessed that their messing around with the tapes at the end of the song would seem so good that Decca would agree to place all of it on the final product. Yet somehow... it just happened.

The mystery of ‘Goin’ Home’, to me, is that although the extended jam does sound a lot like spontaneous improvisation, I find it hard to believe that it was not carefully pre-meditated in the studio (much like, for instance, CCR’s take on ‘I Heard It Through The Grapevine’ four years later). It has a very natural flow to it, and the musicians that surround Mick all keep throwing in various little side melodies that you probably couldn’t think up in the blink of an eye (none of these guys were Keith Jarrett, after all). Unfortunately, information on how precisely the whole thing was worked out is hard to come by, perhaps mainly just because people bluntly assume it was just a studio jam and that’s all there was to it. But no, ladies and gentlemen, Keith Richards does not just nonchalantly produce such smooth melodic passages out of thin air, at least not if you actually watch him improvise during live jam sessions (admittedly, he may have been much better at it in his younger days). In any case, my point is that ‘Goin’ Home’ should not be judged as just a spontaneous outburst of musical expression; it’s an 11-minute piece that has a structure and logic of its own, and while those structure and logic are not particularly complex, there are enough musical ideas in there to allow it to favorably compare to just any other 11-minute track ever recorded, including CCR, The Doors, and any of your favorite prog-rock compositions.

As it often happens with the Stones, the track is a deceptive one. As its slow blues-rock shuffle gradually constructs itself from all the pertinent elements, you might think it’s an unexpected celebration of fidelity and stability: "Maybe you think I’ve seen the world / But I’d rather see my girl", sings Mick in a rather suspicious tone — also, it doesn’t exactly help that the groove itself bears a strong resemblance to ‘The Spider And The Fly’ from the previous year, and we all remember what that one was about. After the three-minute mark, the «song» goes off its hinges and takes this new, strange direction which does not really evoke the image of an aching heart yearning to be reunited with its soul mate — instead, it’s really a cold-turkey type simulation of suffering from acute sexual deprivation. This is the first time on record that we witness Mick Jagger as a writhing, agonizing, possessed animal in search of release — quite a staple of the Stones’ live shows around 1969, but probably quite a shock to all those record buyers and TV watchers who, until then, had only known Mick Jagger as the driving force behind three-minute rock’n’roll singles. Now, as a new age of freedom dawns upon us, the beast is being unleashed within the space of a recording studio — and even if some other beasts, like Van Morrison, for instance, could do such things with more raw stamina and sheer power, we would be hard pressed to find anybody who did it with more pure delight at the opportunity than Mick Jagger. It’s pretty difficult for me to get bored about the jamming on ‘Goin’ Home’ when I see so clearly how much the main star of the show is enjoying all the eight minutes of it.

Besides, the main star is not even the sole star. The jam itself has a decidedly «midnight» feel: throughout it, Brian Jones is incessantly blowing his harmonica in the background, echoing and interplaying with Mick like a mischievous ghost on the faraway horizon. Keith is coming up with one tasty musical phrase after another, playing with tremolo effects on the guitar to procure it with a mystical chimes-at-midnight aura — and every once in a while, Ian Stewart’s piano breaks into the mix with an alarming, early-warning feel. It is even rewarding to listen to Bill’s bass, which also rises and falls with the overall tension and keeps going places — without the technical superpower of a John Entwistle, but with all the imagination of a Paul McCartney. For me, the high peak of the jam arrives around the six-minute mark ("early in the morning... I’m gonna catch that plane... it won’t be long... no... no... no it won’t be long...") — watch out when Keith falls upon that quirky little riff and then he and Mick and Brian and Bill all start working on that crescendo. It’s a moment of incredible live-wire-style intensity — had they given any more thought about structure, they would have used it as a climax at the very end, rather than let that intensity dissipate quicker than it took the time to generate it.

The entire experience is ultimately dark and provocative; it has been justly called the spiritual antecedent to ‘Midnight Rambler’ two years later, and it does share a lot of the attitude — ‘Midnight Rambler’ just turned out to be more «mature», sophisticated, lyrically obscure, ambiguous, and potentially dangerous. But for 1966, ‘Goin’ Home’ might actually be more scandalous than ‘Rambler’ would be for the already much more liberal standards of 1969; also, I do not think that many people simply had the strength in them to put up the exposition and evolution of all the 11 minutes of ‘Goin’ Home’ under a microscope the same way they’d work over ‘Rambler’. They should have paid attention at the very end, though: "touch me one more time... touch me one more time... come on, little girl... you may look sweet... you may look sweet... but I know you ain’t... I know you ain’t..." and that is where the music, after one more dirty lead riff from Keith, comes to an abrupt stop. Actually, we don’t even know, in relation to the protagonist, whether it’s all about fantasizing about his upcoming reunion with the lover he had not seen for so long... or, perhaps, seeing the face of said lover in the facial features of another young thing in his arms right about now? There’s tons of worrying (and thrilling, let’s be honest) moral ambiguity in this performance. «Improvised jam»? No, just one of the most provocative artistic works to come out of the mid-Sixties. The American Decca people who put this at the end of the album were unintentional geniuses — they probably thought that way it would be easy for everybody not to listen to it, but instead they created a Stones record with the darkest ending ever.

Looking back on all this amount of text, it’s almost amazing, in the end, how many impressions and thoughts can come out of a scrupulous look at an album like this — what with the aforementioned painfully limited production means at the band’s disposal, and the occasional necessity to throw in a filler track or two, and Mick Jagger’s single-focused-ly dirty mind, and everything else that whispers to you «well, you know, Aftermath is OK, but it sure ain’t no Revolver or Pet Sounds, right?». Well... in many ways it isn’t, but then again, there are also many ways in which Revolver isn’t Aftermath. I think you’ll find at least about a dozen or so fully original, advanced, beautiful (sometimes sordidly beautiful, but still beautiful) ideas / approaches on here that nobody else did in 1966 but the Stones — and that still feel inspiring and relevant even today (especially if you do not let yourself be fully controlled by the tendrils of political correctness).

Make no mistake about it: with Aftermath, The Rolling Stones permanently secure their status as one of the world’s grandest institutions in the realm of popular music, capable of churning out greatness on a quantitative scale second only to you-know-who. But, as far as I can tell, you do need to learn to look beyond established narratives to see this properly. Neither the «rockism»-colored glasses nor the «poptimism»-tinted ones will provide you with all the relevant aspects of the true story. In reality, on Aftermath the Stones deliver their own narrative on their very own terms, and the juiciest fruits are reaped by those ready for an exclusive subscription.

Only Solitaire reviews: The Rolling Stones

There was a great book written a few years back "I read the news today oh boy" about Tara Browne, written as a labour of love by the author who like a lot of people hear that line in A Day In The Life but never thought much more about it.

It's a great threading together of Browne's life, the declining but colourful fortunes of the Guinness family, Tara's brother's influence and legacy in the setting up Claddagh records as a means of cataloging & reviving traditional Irish music, Tara's experiences and influences in swinging London, and of course connections with The Beatles & Stones both in London and, as mentioned in your review, their visits to Luggala.

https://www.panmacmillan.com/authors/paul-howard/i-read-the-news-today-oh-boy/9781509800049

Another winner, George. Love the british track listing more although us front cover easily better. Their best with brian, including the overrated beggars. So many classic tunes!