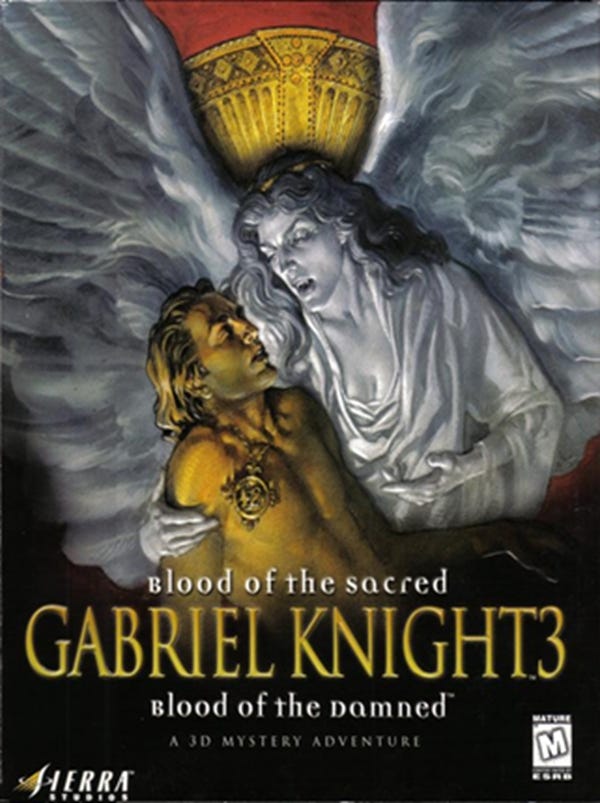

Studio: Sierra On-Line

Designer(s): Jane Jensen

Part of series: Gabriel Knight

Release: November 19, 1999

St. George’s Games: Complete Playlist Parts 1-12 (751 mins.)

Technical features

Graphics

Now here comes the really sad part of the story. As I already mentioned in my other Sierra reviews, upon the decline of interest in FMV games around 1996-1997, the studio (whose death bell has already been rung after the acquisition by CUC in 1996, though nobody knew it at the time) went ahead in two different directions. On one hand, for a while they continued to produce really lovely-looking 2D games, mostly switching to a cartoonish style (e.g. Leisure Suit Larry 7) that was not particularly original, but looked good on the screen and, barring the nasty pixelation effect, continues to look good even today (and if somebody ever took the damn effort to remaster those old games, the way they regularly do at LucasArts, would look even better — that kind of art is very conducive to modern remastering technologies).

On the other hand, with the entire gaming world having begun to embrace 3D, some of the games, most notably King’s Quest: Mask Of Eternity, Quest For Glory V: Dragonfire, and Gabriel Knight 3, would be developed with their own engines, made to run on Windows and DirectX, and feature the ability to move the camera around the protagonist so as to be able to watch the action from different angles. Gabriel Knight 3 was arguably the most advanced of these games and the only one to take advantage of most of the state-of-the-art technology — which is why, unsurprisingly, its shipping had to be delayed for more than a year over the initially planned release date. And was it all worth it?

Sadly, no. In the long run, one of the main flaws of the game is that it would have been far more watchable and playable today, had they chosen to stick to cartoonish 2D imagery instead (say, made it in the style of Charles Cecil’s first two Broken Sword games — those that he made before succumbing to the curse of early 3D himself). The GK3 team certainly have to be commended for designing and building their own 3D graphic engine (called the G-Engine) from scratch, mainly by courtesy of the excellent software engineer Jim Napier; furthermore, they have to be admired for releasing the game in a relatively workable state. I remember playing it on my Windows XP machine sometime in the early 2000s, experimenting with different settings and usually getting along with few problems, though image clipping was definitely an issue and every once in a while your character could vanish into thin air or have nothing left from him / her than a few strands of hair. Technical issues did exist, but they were relatively few and you quickly learned to get around them; a few would be resolved with downloadable patches, and on the whole, as you can see from my playthrough, the game can be run fairly smoothly on today’s machines, with the lengthy loading times no longer a problem and the glitching kept to a minimum by making all the right tweaks to all the wrong parameters.

What cannot be fixed, not even with a diligent effort at remastering, are the ugly early-generation polygonal models that represent the characters. Sure, they look more like actual cinematic human beings than the minimalistic sprites from the early days of 1993’s Sins Of The Fathers, but back in 1993, we took the impossibility of realistically representing the human shape and human motions on screen and had no problem psychologically «inflating» the characters to proper scale. Likewise, while the FMV style of The Beast Within had its sore deficiencies due to obligatory graphic compression, or due to the impossibility of freely controlling your characters on screen, the action as such was still realistic — the actors looked and acted like poor-quality projections of human beings because, well, they were human beings. And then the cartoon-style animations in Sierra games such as King’s Quest VII or Torin’s Passage came along and they also looked nice and smooth, just the way they usually look in actual cartoons.

In Gabriel Knight 3, the onscreen characters neither look too much like human beings when you stare at them, nor feel like human beings when you take control of them and guide them around. More often, they look like human stumps, with grossly simplified and misshapen limbs, plasticine hairstyles, vacant stares, and movements that make C-3PO look like Baryshnikov in comparison. When taken together with the ever so often exaggerated, hyperbolic voice acting (on which see below), this initially produces a very odd effect — as if you’ve been inserted in the middle of some psychedelic marionette show, rather than in an actual murder mystery taking place somewhere in the real world. Eventually, you get a bit more comfortable with that, but even so, the game’s ugly graphic rendering continues to haunt you when, for instance, you are supposed to memorize a complicated series of Masonic handshakes produced by joining stumpy polygonal fingers in clipping-riddled combinations; or when the «vampires», who are supposed to add an atmosphere of bone-chillin’ creepiness to the game, turn out to look like a bunch of straw dolls with emo hairstyles.

One might — and probably should — simply blame it on the inefficiency of computational resources around 1998–1999, since, clearly, this problem is typical of most of the 3D games from that period; but (a) at the very least, given how quintessential Sierra was to the developing and publication of Valve’s Half-Life, couldn’t they have at least gotten somebody from the Valve team to show them how to be more cutting-edge with 3D technologies?; (b) no excuses or explanations can eliminate the fact that those character models looked ugly back in 1999 and look just as ugly, if not uglier, even today. (My rookie opinion on those matters is that there should have been a complete and total ban on 3D character models until at least the age of Half-Life 2; but then, of course, life simply does not work this way).

Things are much better when it comes to background art, much of which has been rendered quite lovingly; on the whole, the architectural vistas of Rennes-le-Château hold their own charm next to their real life prototypes, unless, that is, you try to zoom in on specific details as close as possible (which is something you simply are not advised to do). Even so, interiors fare much better than exteriors — that whole atmosphere of serenity which I was talking about earlier, for instance, may be severely undermined if you decide to examine the grassy knolls and rocks of the countryside too closely — and sometimes the game forces you to do this, like, for instance, when you are supposed to spot the site of a freshly buried object. At least today it is not much of a problem to run the game at its maximum resolution (1024 x 768), which makes it possible to admire things like the paintings on the walls from a safe distance — back in 1999, running the game at max capacity taxed your resources just as much as, say, something like ray tracing technology does in the 2020s.

Yes, it is true that the 3D engine brought a lot of welcome freedom to the playing process — the possibility of moving your character in all directions while smoothly changing the camera angles does wonders for the brain (although, to be honest, this possibility was still limited, since even within a set location, the game operated in «blocks» separated from each other through changing screens, just like in older Sierra games). It was also possible to turn off the cinematics during dialogs, giving you complete freedom to watch your characters talking and gesticulating from any angle — meaning lots and lots of extra work for the programming team. But even so, I distinctly remember myself already back at the time, not at all thrilled about the new developments, all but forcing myself to accept the ugly polygons so as to complete their transformation into beautiful landscapes and realistic human beings inside my own mind. Imagine how it all must feel now, in the age when 3D graphics are often hard to tell from real cinematography?

As the recent attempt at remastering the old GTA games has clearly shown, ancient 3D is all but impossible to remaster — it is much easier to remake such games from scratch than give them a respectable facelift. This means that Gabriel Knight 3, together with its equally unlucky LucasArts companion from the same period, Escape From Monkey Island, has been doomed for all time. The only relief is that, somehow, the game’s critical reputation has somehow managed to circumnavigate its graphical embarrassments — supposedly, the complexity of the story and the characters contributed to this, whereas, on the other hand, the plot and puzzles of Escape From Monkey Island just did not have the proper magic spell to distract players and critics from the horrendous effect of its visual imagery.

Sound

Music does not play nearly as important a part in Gabriel Knight 3 as it does in the previous two games, and this is not so much due to the fact that the series’ principal musical director Robert Holmes had relegated most of his duties to a lesser known (and less talented) understudy, David Henry, as it is to the decision of making the entire soundtrack ever so slightly less obtrusive and active, less focused on catchy or haunting themes and more on creating a general sonic ambience. Most of the outdoor action, in fact, has no music at all — that «serenity» atmosphere I was talking about is rather achieved by the sounds of the birds and the brooks and the wind, rather by anything man-made. Meanwhile, the indoor themes are largely dominated by gentle synthesizer hum and tasteful little impressionistic piano melodies (somebody’s clearly been listening to a lot of Satie in his spare time, be it Robert or David).

The music does get predictably louder and more dangerous during certain dialogs and cut scenes, providing its fair share of suspense (usually not resolving to anything too serious, given the game’s plot conventions), but in general, I would say that if you are bound to remember any of this soundtrack, it’s more likely to be one or several of the melancholic-nostalgic piano tunes that accompany the more sentimental aspects of Gabriel’s world-saving mission, or of Gabriel and Grace’s doomed romance. In fact, there’s a bit of a tasty paradox in here: even as Gabriel Knight 3 in general raises the stakes on the epicness and monumentality of the narrative, its music actually sounds less dramatic, monumental, and Wagnerian than it did in the previous two games. The opening themes there were either driving and tempestuous (Sins Of The Fathers), or doom-laden and dreary (The Beast Within); the opening theme of Gabriel Knight 3, despite some furious acoustic strumming and crashing cymbals, is dominated by a sad and intimate piano melody that already presages the sad and intimate ending of the game before it has even started. It sort of gives you your first big hint that you may think this is a game about saving the world from the anti-Christ, but in reality this is a game about how an inflated ego can ruin the personal future even for a guy with the best of intentions, or — to complicate matters even further — how kind-hearted altruism and unbearable egoism can suddenly turn out to be two sides of the same coin.

The game does occasionally recycle themes from its predecessors, mainly to ensure continuity (for instance, the perennial ‘When The Saints Go Marching In’ theme is, for some reason, playing at the bar in Rennes-les-Bains, and the ‘St. George’s Books Theme’ from the first game sometimes crops up during Gabriel’s dialogs with Grace, triggering a bit of nostalgia for your first ever experience with the series), but this is not a big goal for the composers. Perhaps they thought that such «lazy», inobtrusive musical backing would work better in a 3D setting — and perhaps they were right if they did. I can only say that some of those piano themes did end up becoming earworms eventually (there’s a particularly dark-romantic theme ringing during Grace’s exploration of Montreux’s library that I always yearn to hear), and that the emphasis on the piano does give the game its own unique color, as opposed to, say, the emphasis on dark synthesized cellos in The Beast Within.

In any case, whatever be the ultimate comparative judgment, I can find no serious faults with the game’s musical soundtrack, which is, unfortunately, not the case when it comes to the voice cast. With 3D animations replacing the short-lived FMV fad, we are now back to pure voice acting mode — a good thing for video games which, even in 3D mode, still have more in common with cartoon animation than real acting. This time around, however, Jensen seems to have found herself with a much more restricted budget that did not allow for another star-studded cast like Sins Of The Fathers. Most of the actors here are professional, but relatively small-time players, which, unfortunately, makes itself noticeable rather quickly. Jensen’s only «success» was in being able to make Mr. Tim Curry in person reprise his role from the first game, wiping out the shadow of The Beast Within’s Dean Erickson and probably sending thousands of fans into paroxysms of sweet delight when the casting was announced. Alas — who knew this decision would turn out to be the second most tragic decision about this game? (The first one, of course, was the decision to make it in 3D.)

I am not entirely sure of what happened to Tim Curry’s attitude between 1993 and 1999; I can only assume that he got six years older, and probably thought his character should have also gotten six years older — and sixty times as obnoxious. The Gabriel Knight of Sins Of The Fathers was a confident and sarcastic, yet also naturally curious and excitable young man, whose nasty attitude was largely reserved for inadequately arrogant pals such as Detective Mosely, and whose womanizing ways at least formally had a sort of gentlemanly sheen. You would have thought that after being «cleansed» from his sins upon assuming his role of Shadow-hunter, and after several years spent carrying out Shadow-hunting duties in Europe, Gabriel Knight’s «knightly» qualities would have become enhanced, while the (still somewhat lovable) assholish properties of his character would have faded away due to all the proximity to so much holiness. Particularly after that whole werewolf thing in the second game, when his very spiritual essence was at stake and all. The Gabriel Knight we would all be expecting in the third game would certainly be a wisened up, more reflective, more responsible sort of fellow — hopefully, still retaining his sense of humor and a bit of the old mischievousness, but definitely more somber, melancholic, and solitary than he was when we saw him last. That is, provided we’re actually following believable patterns of character evolution.

Apparently, though, «believable» is not a proper word to be pronounced in the presence of the respectable hero of the Rocky Horror Picture Show. Six years later, Tim Curry’s Gabriel Knight has transformed into a seriously cheeky, know-it-all, mock-it-all character who now speaks about twice as slow as he used to, making sure that each of his syllables is drawled in the most obnoxious and sarcastic way possible. Even the formerly self-respectable and slightly mysterious introduction of "Knight. Gabriel Knight" has been transformed into "Kn-n-n-n-ight. Ga-a-a-briel Kn-n-n-ight" as if he were mocking himself, yourself, his name, God, and the French government at the exact same time. And he does that CONSTANTLY. The only reason why Jane Jensen did not have the guy fired midway through is, unfortunately, because that was probably the exact way she wanted her character to behave — in fact, some of Gabriel’s dialog seems to have been specially tailored for that approach.

There are veteran gamers out there who claim to have been turned off by Curry’s faux-New Orleanian accent and cocky phrasing from the get-go; myself, not being able to tell very properly a real New Orleanian accent from a fake one produced by an English person, I was never bothered by the lack of authenticity, preferring instead to find pleasure in the mildly ironic, mischievous, but well-meaning intonations of Curry’s Gabriel Knight in Sins Of The Fathers. Maybe he was not a true New Orleanian, but he played a truly colorful individual all the same. Skip ahead to Gabriel Knight 3 and that truly colorful individual has mutated into the kind of person you usually want to whack with a stick on Facebook even without actually hearing his voice. That’s a «Schattenjäger», sworn to fight evil and protect the innocent? Okay, so maybe you don’t need him to talk like the Dalai Lama, but when a typical observation on the street reads "I have no idea who lives here, but they’re probably not interested in meeting me... well, I know it’s hard to believe, but, you know, they’re French!", I’m sure that Jesus is quietly weeping up there in Heaven, traumatized by just how much the bloodline has degenerated over the millennia.

Granted, it’s not always that bad; once you get a little used to the drawling speech tempo and the never-ending waves of sarcasm, the pauses between truly cringeworthy moments slowly start getting larger — however, they never cease altogether, and by the time Gabriel receives his final epiphany at the end of the game, it is all but impossible to take his «transformation» seriously, seeing as how we were so completely unprepared for it. As I already wrote in the previous sections, Jane Jensen bears the lion’s share of responsibility for turning a once beloved character into a barely tolerable asshole, but Curry willingly hops on that train and seems to be really having fun here. As a particularly «so-bad-it’s-totally-unforgettable» moment, I invite you to watch this little interaction between Gabriel Curry and the proverbial French maid — trust me, there was nothing even remotely like this in the first Gabriel Knight game. The intonations alone are enough to melt the ears ("WOULD YOU BE ABLE TO CLEAN THEM FOR ME?"), but somebody also had to write that dialog... and that somebody was the same person who provided a fully rewritten version of Le Serpent Rouge for one of the most elegantly complex adventure game puzzles ever designed? Man, the world is even less black-and-white than we thought...

Well, at least Curry’s less-than-stellar performance is somewhat compensated for by the splendid work done by Charity James as Grace Nakimura, our second protagonist whose role in this game is every bit as important as Grace’s role in The Beast Within — and on a scale of 1-to-3, I would say that while Charity’s delivery comes slightly behind Leah Remini’s in the first game in terms of clarity and likeability, it certainly restores Grace’s original cool-headed, neophytically-intellectual nature as opposed to the somewhat psychotic, deeply imbalanced behavior of The Beast Within’s Joanne Takahashi (which was not too bad by itself, but simply did not feel believably compatible with Remini’s portrayal). James sort of borrows all the good qualities of Curry’s Gabriel — smart, sarcastic, confident, ultimately well-meaning — while leaving out most of the bad ones — the smugness, the offensiveness, the propensity for bad jokes. Even when she sounds condescending (be it to Mosely or to any of the clueless locals), there’s usually a whiff of sympathy to be heard in her voice, rather than straightahead mockery.

And that’s even without mentioning how good she is at regular phrasing — right from the start, she displays a phenomenal command of all sorts of microtones, whispers, groans, sneers, and gasps, which really brings her close to the player. Roaming all over the hotel and the countryside with Grace after you just explored those locations with Gabriel is a true delight, since, unlike Gabriel, she is able to mix her irony with sincere admiration, rather than just scoff at everything in sight. At this point, I’d say that Jensen gets to be a much better writer from the female perspective (duh) than the male one, and Charity James is a great choice to voice that perspective. (Fun fact: the very same year, Charity James also voiced Governor Elaine Marley in Escape From Monkey Island — making her, in a sense, the Valkyrie of classic adventure games conducting them to their final resting place. Unfortunately, she didn’t have much of a memorable career ever since).

The rest of the cast is hit-and-miss; even if some of the actors went on to become legends or semi-legends in the business, too many of them are reduced to comedic Clue-style stereotypes by the script. The saddest tale is that of Jennifer Hale, soon-to-be one of the greatest video game voice actresses of all time (hello, Commander Shepard) but here forced to fake an unconvincing French accent as Madeline Buthane, the sexy-secret-agent-femme-fatale leader of the tour group. Jennifer seems ready and willing to play a caricature, but the grotesque portrayal quickly gets annoying (even so, Hale’s talents are very much on display as she revels in practicing various degrees of «removing the mask» over the course of the game, effortlessly alternating between fifty shades of «suave» and fifteen more of «dangerously suave»). Another link to Mass Effect is Carolyn Seymour, the future voice of the motherly-memorable Dr. Chakwas, here playing Estelle Stiles, the admiring companion of ex-actress Lady Howard — with her voice arguably affected less with theatrical / hyperbolic mannerisms than others, her companionship is perhaps the one I crave the most during my playthroughs. (Unlike Lady Howard, voiced by Samantha Edgar in the most overbearing manner possible — although, granted, the character is supposed to be overbearing and insufferable).

Special mention should probably be made of John de Lancie in his role of Montreaux, the owner of the mysterious Château de Serres — he only gets about two scenes in the entire game, but tries real hard to provide a bit of a Hammer Horror atmosphere for both of them, playing a character somewhere in between Vincent Price and his own Q from Star Trek as he veers between taunting and horrifying his interlocutor. Montreux’s lengthy monolog on immortality and eugenics in the middle of the game is a far cry from the psychological creepiness of Baron von Glower’s ruminations on human and animal nature in The Beast Within, but it’s still quite a delicious throwback to those days when theatrical villains could fling their simplistic philosophy at the viewer and you’d lap it up just because the intonations were so seductive.

On the whole, though, the cast really suffers from the sin of overacting. Perhaps most of those guys had their background in theater rather than cinema or TV, or maybe they were just cued that they all had to make the absolute most of their voices before the microphones — or maybe they all tried to follow the lead of Tim Curry, so much in love with his own voice that he feels as if it were the greatest gift a player could ever receive in one’s lifetime. Against the background of constant hyperbole, rare exceptions such as Simon Templeman’s relatively quiet and courteous impersonation of Prince James of Albany tend to get lost in the overall impression. Fortunately, much of the game will be spent in relative silence as Gabriel and Grace simply explore the environment and solve their challenges without having to engage in fussy dialog with the stereotypical stock characters of French, Italian, or Australian backgrounds.

Interface

With a unique 3D engine came a brand new interface that, like just about everything else in the game, somehow managed to combine cuteness and comfort with ugliness and incoherence. Moving your playable characters around was relatively easy, except that the game included no options to vary their speed — both Gabriel and Grace apparently regard it as way beyond their dignity to run around the place, so when you’re out in the countryside, moving from one spot to another can take far more time than the average impatient gamer would want to allow oneself. At the same time, camera controls are engineered in such a way that you can pan out or move away from your character (either standing or moving) as far as the environment allows you to — which is actually the (odd) way to make them traverse a large span of territory: set Gabriel or Grace in motion, quickly move the camera to the spot where you want them to be, then click the move button again, and presto, they appear on the spot in a couple of seconds rather than in half a minute, which would be the appropriate time if you’d been focused on them all through their movement period instead. Einstein would be proud!

This feels a little weird, but it’s easy to get used to; much worse is the fact that, due to the roughness of 3D graphics, large masses of space can feel disorienting, and the connection points between separate blocks are rarely evident. Usually, the mouse arrow changes into a special «exit shape» whenever you come across such a point, but ever so often, it’s a real chore to locate it, especially in all the valleys and ravines of the countryside, some of which are connected by minuscule, hard-to-locate passages and some require taking the bike to get to. Other games reserve their pixel-hunting for finding and picking up various small objects; in Gabriel Knight 3, most of that process will be reserved for finding the various exits.

General interaction with objects and people is handled in more of a LucasArts than a Sierra way: click on anything clickable and the game highlights the target with a set of tiny icons that represent either actions (‘take’, ‘open’, ‘push’, ‘talk’, etc.) or, if you transition into dialog mode, the various topics for conversation. The icons are nicely designed, even if you cannot always properly decode their meanings before clicking on them — and even if some are clearly added merely to tickle you with the illusion of choice. For instance, many of the windows in the game are accompanied with the ‘open’ option, but there’s maybe two or three windows overall that you can actually open. Some of the choices merely remind you of the happy innocent days of the parser, when you had to use your own brains and imagination to try out various fantastic and outrageous scenarios of resolving the situation, rather than rely on somebody else making a pre-designed menu for you — e.g. when you need to get the French maid out of the way to search the guests’ rooms, there’s a ‘bind and gag’ icon cropping up, whose only purpose, apparently, is to earn you a "you must be sick!" rebuke from Gabriel. Yeah, right. If I must be sick, why did the game designers put that icon up in my face, expressly saying ‘click me!’, in the first place? At least in the days of the parser, that would really be me taking on full responsibility for my perverse actions.

The dialog trees are constructed nicely and aesthetically, and, like it was in the second (but not the first) game, dialog topics gradually disappear as you exhaust them one by one. The downside is that, apparently, this time around there is no way to keep an in-game track of your conversations; Gabriel has a tape recorder and Grace has a notebook, but you cannot use them to pick up on what you have learned from other people, which is kind of a bummer given the wealth of historical and current information that is going to be piled on you throughout the game. As for choices, those are pretty much non-existent, but that’s the way it has always been in Jane Jensen games — there’s absolutely no way that she is going to let you flesh out her beloved characters, Gabriel and Grace, according to your preferences. You can sometimes try out different solutions to a single issue (for instance, making a ton of fake IDs in preparation for your first meeting with Montreux), but only one of them is going to work anyway.

Speaking of making IDs, much of your gametime, particularly when you are playing for Grace, is going to be spent playing around with «SYDNEY» — the dynamic duo’s supercomputer that multi-tasks as an encyclopaedia, a data repository, and a set of analytical tools. Again, it takes a bit of time to get used to its interface, but on the whole, it is quite impressively and logically organized, and although some of its AI abilities border on the magical (for instance, a universal system of machine translation that severely beats GoogleTranslate and everything else in terms of accuracy — back in 1999!), the overall feel is quite serious. You can actually get lost browsing the information database on all things mythological, mystical, and occult alone — granted, most of that stuff was loaned by Jane from the online Mystica encyclopaedia (which is still going strong as of 2023), but at least it’s far more useful reading than, I dunno, trying to memorize all the fictional lore of the Faerûn or Elder Scrolls universes. And as for that toolkit... well, I’m not sure that you can have such a lot of fun with it beyond just using it to solve the required puzzles, but I certainly cannot find a lot of flaws with the organization of its geometric and linguistic sections (and, as I already said, I sort of hate geometry).

Another specific difference from the first two games is that Gabriel Knight 3, to a certain extent, plays out in real time. Stick around for long enough and you shall find some NPCs occasionally changing their locations; worse, stick around for long enough without doing the right thing and you shall be locked out of certain point-earning achievements and useful bits of information. There is, for instance, a particularly tricky moment in the middle of Day 2 when the tour group has just returned to the hotel and, in order to get the full number of points, you have to catch all of the members doing certain things — which is only possible if you perform all the actions in a very specific order and in a very limited time window. On the other hand, in most cases time does not advance properly until you’ve completed the required actions, so you can make a million trips all over the valley and still not move from the morning into the afternoon section — this inconsistency is not particularly bothersome, but it does make one question the validity of introducing time-dependent puzzles in the first place.

The most annoying time-dependent puzzles are, of course, the pseudo-«action» bits in the last section of the game — where you have to be quick enough to jump on a pendulum or shove your talisman into the monster’s face — because these are the only sections in which Gabriel can actually die, and saving and restoring your games takes time, which is particularly annoying if you realize that those deaths were not so much the result of your stupidity as the result of being introduced, without warning, to a completely different type of puzzle (pendulum), or the result of your wishing to simply look around and explore a new location before bringing the game to its end (monster). Fortunately, it’s really just a couple of special situations, not enough to kill off the fun. Also fortunately, there’s a way to «retry» each death situation even if you forgot to save; and as far as I know, the game, just like its two predecessors, features no dead-end situations whatsoever (you can easily miss stuff that earns you lotsa points, but none of it is really crucial to beating the game as such).

One final, relatively minor, complaint actually concerns the game’s general interface as such — aesthetically, it sucks. The overhead menu which, thankfully, remains hidden by default; the notifications about gaining extra points; the subtitles at the bottom of the screen — all of that is rendered in a small, primitive, ugly font that somehow feels very dissonant with the graphics and is a really far cry from Sierra’s generally tasteful approach to font and notification design in their games. You could certainly blame it on the newness and complexities of the 3D engine, but we have the example of Quest For Glory V, which was also done in (partial) 3D and handled the interface and font design issue so much better. Both the first and the second Gabriel Knight games had quite a bit of love invested in their interfaces — particularly the first one, with all of its silver-gray Gothic stylistics — so it’s a bit surprising just how bureaucratic and perfunctory the overall style of Blood Of The Sacred comes across in comparison. I guess it’s really no biggie compared to all the more serious issues listed above, but this is a video game, not a rescue mission — packaging is important here if you really want to convince your customers that you love your own creation as much as you want them to love it, right?..

Verdict: «The Godfather Part III» of video game trilogies — you’ll probably start out by hating it, then accepting it as an inevitability.

Few games illustrate the difference between «failure» and «deeply flawed success» as transparently as Gabriel Knight III. So many technical and substantial problems haunt Jensen’s last serious investment in the story of her favorite protagonist that writing the game off as a catastrophe is a very easy option, especially when you have influential websites such as Old Man Murray on your side. My own problems with the game run much deeper than the ugly 3D graphics or the outrageously designed Cat Moustache Puzzle — I can only wonder, for instance, at the perfectly executed double plot by Jensen and Tim Curry to reduce their formerly elegantly controversial character to the level of human caricature; like, what they were even thinking?.. unless, of course, the reason is that by this time Jane herself was disgusted with the concept of Gabriel Knight and determined to fortify him in his male-chauvinist-pig image while at the same time redirecting all of our sympathies to Grace. In doing so, however, she created an inconsistency rift with the previous two games, which is a pretty big sin on the universe-crafting scale. «Mean Asshole Saves The World» is hardly my preferred idea for a great game, because you have to be saving the world (boring! how many more times does this stupid world need saving? let the anti-Christ triumph already!) and you have to be the mean asshole doing it. If I’m saving the world just so that Gabriel can poke more stupid jokes at his friend Mosely, I’d rather let the «night visitors» keep doing their thing.

Yet at the same time, there’s simply too much good about Gabriel Knight III to let it wallow on in infamy. For one thing, it tries to do something different — each game in the trilogy has its own face, establishes its own structure and patterns, never ever gives the impression of «oh, this worked so well in the last game, let’s try it again» (compare this to LucasArts’ swan song, Escape From Monkey Island, which observed that rotten principle almost religiously). Well, okay, perhaps bringing Detective Mosely back from the dead wasn’t such a hot innovative idea and should probably count as a case of «fan service», but other than that, the game seriously tries to take Gabriel Knight into a completely new direction. From that point of view, its monumental ambitiousness may not so much be a sign of Jane Jensen’s ego as it is simply a fresh approach — «let’s do something really grand now, seeing as how we’ve never yet worked on that scale before». Maybe it doesn’t work as efficiently as it did before, but you definitely cannot accuse the designer of simply following the tried and true.

For another thing, I have always been and remain totally enamoured of the calmness of this game. Yes, there are tons of games out there in which you have to save the world, but most of them usually lay on the pathos and the epicness all the way through (even The Longest Journey, a big favorite of mine, is a hot mess where DRAMA can reach you and whack you over the head at any given point in the overall post-modern setting of the game). Here, you’re simply set to roam over the green pastures of the French countryside, basking in the sunshine, enjoying the peace and serenity and, oh yeah, doing some research on vampires and Knights Templar along the way when you feel like it. In a relaxed situation like that, even Tim Curry’s nasal ironic twang occasionally becomes bearable, while Charity James’ croaky chirping is just adorable. It all adds a certain degree of close-to-home pseudo-realism that none of Sierra’s pre-3D era games could boast.

Finally, there is the intellectual content — okay, faux-intellectual, as we are dealing with a gross historical hoax molded into mystical fiction, but, as usual, it is always delightful in a Jane Jensen game to separate true history from flights of fantasy and conspiracy theories, and the sheer amount of work that went into fleshing this mix of fact and fiction into a set of puzzles is bewildering. Maybe this is not sufficient ground for emotional love, but it certainly deserves respect and admiration; compare the effort to, say, Charles Cecil’s similar exploration of the same themes in Shadow Of The Templars and you will see what it is that separates lightweight amateurishness from serious scholarly devotion — Cecil essentially operates on the level of a comic book reader (although he has many other talents to compensate for this), whereas Jensen must have spent months in the library. The end result of it all is that, whereas New Orleans and Munich are two places I’d like to visit (actually, Munich has already been covered), Rennes-le-Château is one place where I wouldn’t mind retiring.

All in all, my only advice to any potential retro-player is: do not play this game until you have explored — and appreciated — the previous two parts of the trilogy. Although it is formally a stand-alone title, it has to work in conjunction with Sins Of The Fathers and The Beast Within, for better or worse. Neither its relative charms nor its relative deficiencies shall be as transparent to you as they will if you play all three games in the correct order. Nor is it absolutely imperative, in fact, that you play it even if you did enjoy the other two — while it adds a whole new layer to both the story of Gabriel’s path to destiny and to the sad tale of «good guy and good girl can’t get together because they’re too out of touch with the simple things in life», this layer is not really something that was even faintly hinted at before; the game does not really serve as a long-awaited answer to any deeply burning questions asked in the previous ones.

But if you do play the first two games and then make an effort to get used to this one, chances are it’ll leave an impression all the same. Deep at heart, it’s a tad more solemn and melancholic, more prone to make you ponder upon the meaning of life and the paths you’re choosing; look past its multiple flaws and you might feel that for Jane Jensen, Gabriel Knight 3 is more or less the same that Quadrophenia was for Pete Townshend in 1973 — a creaky, leaky, but monumental achievement where the author himself or herself realizes that this is essentially as deep as s/he will ever be able to go, and that post-release exhaustion sort of stays with them for all their life. And was it truly such a coincidence that Gabriel Knight 3, a «swan song»-type of game if there ever was one, was the very last of classic Sierra adventure games ever published? I don’t think so. On the contrary, I’d like to think of it as a pretty damn good candidate for the status of «Ideal Game To Close The Book On The 20th Century» — released just at the time when games like The Longest Journey were opening the door to the 21st...

This and other video game reviews at St. George’s Games

One of the most incredible aspects is that after playing GK3, the Italian writer and illusionist Mariano Tomatis developed an obsession with Rennes-le-Chateau that culminated in him being made curator of the actual Rennes museum… which he proceeded to refashion after the game’s museum:

https://www.artribune.com/progettazione/new-media/2019/11/gabriel-knight-3-videogioco-museo/

(In Italian, help yourself to some Google Translate)

Speaking of Italy, I sometimes think about the similarities between Gabriel Knight and Tiziano Sclavi’s Dylan Dog: both are good-looking, slightly chauvinist ex-cops who investigate on various gruesome things which may or may not have a supernatural explanation and find out they come from a looooong line of… but I don’t want to give you any spoilers 😉

Mm, Satie?

I thought those piano pieces mainly ripped off several of Chopin's preludes.

And I loved every bit of them.