Game review: Maniac Mansion (1987)

Studio: LucasArts

Designers: Ron Gilbert / Gary Winnick

Part of series: Maniac Mansion

Release: October 5, 1987 (Apple II) / March 12, 1988 (IBM PC)

St. George’s Games: Complete Playthrough

Basic Overview

Maniac Mansion may not be the best adventure game of all time — if anything, it was simply released way too early in the history of the genre to stand a chance — but it might as well be the single most innovative adventure game of all time, period. Its arrival on the scene had, in some ways, a similar impact to that of the arrival of the Mac in 1984: a daring, dashing, arrogant young competitor to the dominant «generic» formula at the time — firmly establishing Lucasfilm Games (later to be known as LucasArts) as a fresher, hipper alternative to Sierra On-Line.

Much of that innovation was purely technical, with too many innovative features to list in a single sentence — the invention of the point-and-click interface; the multiple branching paths to increase replayability; the never-get-stuck-on-a-puzzle game design; the interrupting cutscenes, etc. — but in terms of immersion and atmosphere, what mattered most was the very, very special vision of principal game designer Ron Gilbert. Where the writers at Sierra went for fairly well-established routes — the fairy tale setting of King’s Quest, the comic sci-fi universe of Space Quest, the realistic world of Police Quest’s crime and punishment — Gilbert took an approach hitherto unseen in computer games, inventing an imaginary world that was equal parts Back To The Future, Monty Python, and The Addams Family: futuristic, satirical, and absurdist. This was a game which could be funnier than any other game at the time — but it would take a slightly special kind of mind to appreciate its humor. More than anything else, it constantly required you to think out of the box, both with its endless slew of not always obvious cultural references and its approach to the art of puzzle-solving. And how would it be physically possible not to think out of the box, might we add, in the context of a game in which you are supposed to save the world from a mad scientist whose mind has been enslaved by a sentient meteor, whose couple of trusty henchmen consists of a friendly Green Tentacle and a less-than-friendly Purple Tentacle, and whose autistic son is prone to violent fits of rage over an improperly microwaved hamster?

It will hardly come as a surprise that Maniac Mansion failed to become a serious commercial hit upon release, even though the critics largely loved it — compared to contemporary Sierra games, it must have looked way too bizarre, and largely appealed to the same kind of hip people who’d always preferred Frank Zappa over Peter Frampton. But the very fact that the management of Lucasfilms gave it the green light speaks volumes about the state of the game industry at that time — the whole thing was still so new, and its foundations were still so wobbly, that even the «craziest» ideas could find themselves supported by the industry bosses, rather than remain the sole property of basement-locked indie designers. For all it’s worth, Maniac Mansion could be forever remembered as «Gilbert’s Folly»; fortunately, it came at such a convenient time that it is instead remembered as one of the greatest adventure game titles of all time — provided, of course, that somebody is still willing to remember anything about a 30-year old adventure game.

Content evaluation

Plotline

There is nothing particularly unusual about the game’s plot — a fairly ordinary story about a mad scientist, living in relative isolation inside a fairly ordinary mansion on a hill, accompanied only by his fairly ordinary fanatical wife, Nurse Edna, his fairly ordinary autistic son, Weird Ed, and two perfectly ordinary tentacles — Green and Purple. When a regular sentient meteor crashes close to his house, the alien entity and the mad scientist form a crazy alliance which, as it turns out, requires the brains of a human to allow the meteor unleash its extraordinary powers and take over the world. Subsequently, Dr. Fred kidnaps Sandy, the girlfriend of the game’s protagonist, and it is now up to you and your friends to break into the mansion, neutralize its inhabitants, save Sandy, and liberate the world from the alien menace.

The plot, quite intentionally I guess, reads like an early Ed Wood script, but if there was one thing Maniac Mansion was really not about, it was telling interesting stories — much, if not most, of the game is simply about roaming around the spacious mansion and finding a way to break through to the poor captured Sandy, with an occasional cutscene or two showing Dr. Fred gloating over his soon-to-have-her-brains-sucked-out captive to raise tension (not to worry, though, as you can never truly run out of time). The only true function of the plot is to turn inside out every old sci-fi, horror, and teen comedy cliché which spontaneously creeps into the writers’ twisted minds.

The bad news is, this being LucasArts’ first proper experience and all, the game is extremely skimpy when it comes to dialogue — most of the characters’ replicas are laconic to the core, and any proper «development» is largely constrained to the cutscenes, in which the bad guys occasionally insinuate a sordid detail or two ("He hasn’t been at dinner for 5 years... and he’s been bringing those bodies down into the basement late at night", a worried Weird Ed tells his mother). In just a few years, Day Of The Tentacle would establish all the personalities of Dr. Fred’s family members with far more precision and humor; here, they are essentially cardboard figures whose bizarre goofiness is hinted at rather than properly illustrated. Even so, some of the plot twists — such as Green Tentacle’s plans to start a rock band, or Weird Ed’s sentimental relationship with his pet hamster — are quite unique for the likes of 1987. More importantly, the overall absurdity of it all frees the writers to conduct really wild experiments when it comes to puzzle design.

Puzzles

With the free-form parser of Sierra’s early adventure games kicked in the dust and replaced by a fixed selection of verbs (see Interface for more details), one might think that the average difficulty of the puzzles would go down a notch or two — and maybe it does, given that you no longer have the opportunity to type in names such as Ifnkovhgroghprm (up yours, original King’s Quest!), but since there is still a pretty impressive variety of verbal options, a huge number of objects to pick up or interact with, and different paths to try depending on the characters you have picked, expect no mercy — I remember getting hopelessly stuck in my original playthrough back in the old days because my mind simply wasn’t sharp enough to consider the right options out of a sea of possibilities.

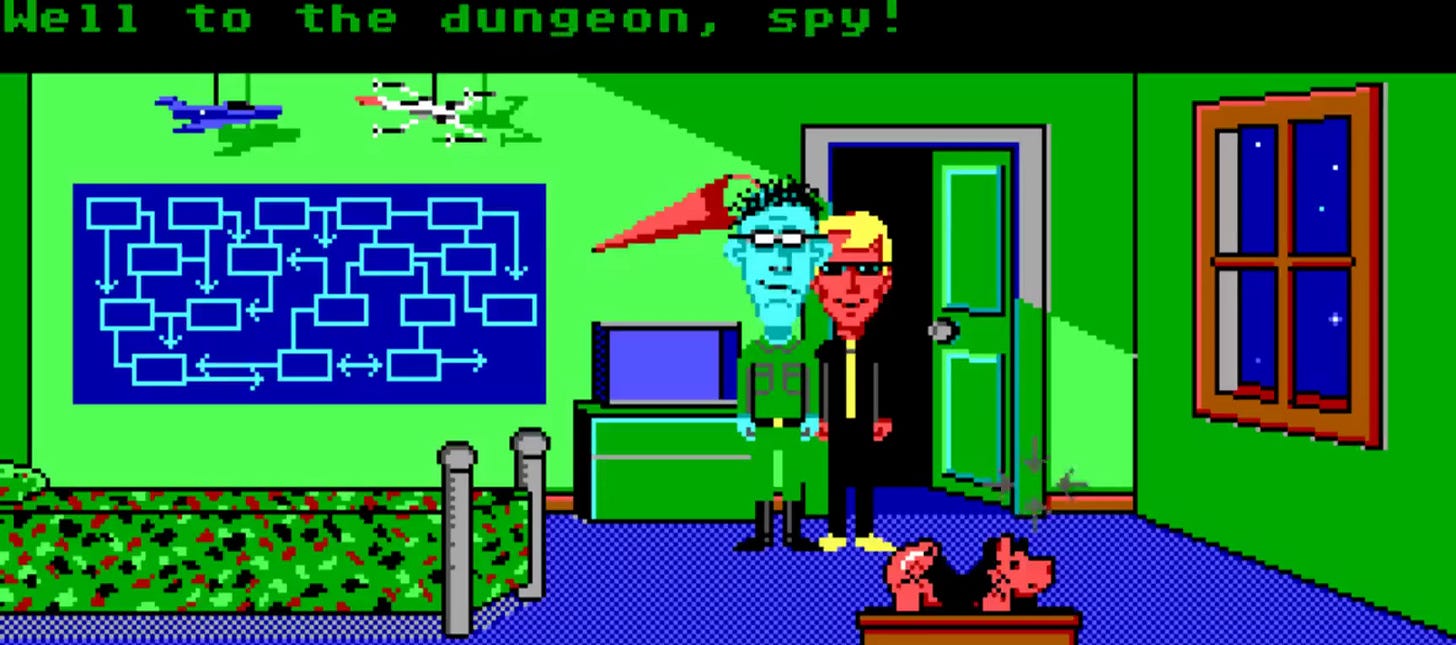

Since the game, like most of the LucasArts games that followed, revels in its Pythonesque absurdity, brace yourself for occasional moon logic puzzle alert — although if you truly get into the whacky spirit of the game, you will soon find yourself adapting to the fairly logical rules of its parallel universe. The trickiest puzzles are actually those which require the use of more than one character: this is something to be always kept in mind when, for instance, you find yourself seemingly stuck and lost for good after you have been thrown in the dungeon by one of Dr. Fred’s family members. And, of course, given that some of the party members have their own specific abilities — some are tech savvy, some can sing and/or play the piano, some have writing talent, etc. — the solutions to these challenges will vary from one playthrough to another.

Other than that, and an occasional impediment in the form of somewhat irritating red herrings (did anybody ever figure out what to do with all those broken bottles of ketchup in the fridge?), the puzzles are not particularly challenging when you think back on them — certainly nowhere near the level of Day Of The Tentacle in terms of complexity or inventiveness.

Atmosphere

Gilbert and Winnick’s intentions were clearly to immerse the player in an atmosphere of «goofy horror», and to a large degree they have succeeded — as a young teenager playing the game, I remember feeling amused and genuinely scared much of the time. The Mansion, as befits any Mansion in a suspense-filled setting, is vast, suspiciously devoid of occupants, peppered with creepy portraits and dangerous-looking objects, but every now and then you discover that, for instance, those blood stains on the wall near the rack of knives are actually ketchup, or that the hungry and mean-looking Green Tentacle actually wants to be your friend so that you can help it assemble its own rock band and go statewide.

The Mansion’s inhabitants all look like vicious mutant creeps (even if they are portrayed as grotesque caricatures), and as you explore the rooms and corridors, there is constant tension, since occasionally they like to venture out on the prowl (especially the cheese-addicted Weird Ed) — yet the worst thing Weird Ed or Nurse Edna can do to you is throw you in the dungeon, which is relatively easy to get out of. (Just don’t mess around too much with Weird Ed’s hamster — this is one of the things that can actually trigger a bad ending). Even so, it can get pretty nerve-wrecking when you have to avoid the evil Purple Tentacle in pitch black darkness, or to quickly perform a timed action before getting blasted in a nuclear meltdown of Dr. Fred’s reactor in the basement. Considering that, unlike future LucasArts titles, you can actually die in this game (and sometimes take all the world with you when you do), it is notoriously creepier than Day Of The Tentacle or any of the Monkey Island games.

The reassuring news is that Maniac Mansion also introduces the concept of the confident, nonchalant, not-give-a-damn hero from a first person perspective — unlike Sierra, whose protagonists felt somewhat detached because all of their interaction with you was mediated through a third-person narrator («You open the door and step inside», etc.), LucasArts prefers that your characters reply to you themselves, sometimes turning to face the screen and speaking in your face («I can’t do that», etc.). And since in most situations, even the dangerous ones, their reactions are usually cool, calm, and collected — I mean, what can be more ordinary than climbing through a hole in the ceiling atop the stalk of a giant carnivorous plant? — this certainly defuses the feeling of terror.

Technical features

Graphics

Maniac Mansion’s innovations in the visual sphere were far more subtle and less striking than its basic interface and gameplay system, but if you compare the game against its main competition at the time — once again, Sierra, of course — the difference in style is pretty striking. In most versions of the game, the verbal interface and inventory slots cover much of the screen, leaving a relatively small widescreen space which begs for a more close-up, even mildly claustrophobic approach. Since most of the game takes place inside the Mansion (rather than against Sierra’s typically vast outdoor landscapes), this gives Gary Winnick a good excuse to concentrate on the details and make the space around us, in a way, more welcome and intimate. Everything is big and thick — the tables, the chairs, the beds, the portraits on the wall — even giving you a chance to actually read the writings on Green Tentacle’s posters (‘DISCO SUCKS!’). Throw in the juicy, opulent colors of the EGA version, and you will be surprised to see that, graphics-wise, the game still holds up today in all of its grotesque, cartoonish glory.

Best of all are the character sprites — compared to Sierra’s tiny moving cubicles on matchbox legs, the PCs and NPCs of Maniac Mansion actually give the impression of live figures, largely due to being two or three times as large as the typical Sierra sprite. To make the characters even livelier and friendlier, Winnick endows most of them with disproportionately large heads, which allows to paint real eyes, noses, and mouths and animate the faces, even if portraying emotions is still a long way off. For the first time in adventure game history, you can actually feel some affinity for the characters you are playing as, even if, unfortunately, there are still no true close-ups (even the cutscenes always play out in the exact same interiors; in this respect, Sierra actually got the upper hand on LucasArts by introducing true close-ups in Leisure Suit Larry).

Sound

This is pretty much the only aspect of the game about which the less is said, the better. The game came out in the pre-SoundBlaster era and never got a proper remaster, so you will simply have to endure the PC Speaker — fortunately, the game keeps quiet most of the time, other than the opening and closing music (the main theme does manage to be quite catchy, though, in a James Bond-theme kind of way). Alarms (and there are quite a few of them scattered around the Mansion) are a real pain in the eardrums, though, as is the Tentacle Mating Call when you attempt to play it (then again, these are precisely the kinds of situations in which the ugliness of the PC Speaker actually helps preserve the immersion rather than break it).

Interface

What with Maniac Mansion’s status as the Big Old Mother of all point-and-click adventure games, I have a strong ball of acid hate reserved for it next to all the mushy love — it was, after all, the game which ultimately killed off the text parser, even if it took a few more years to stomp it out completely (Sierra stubbornly held on to the parser until about 1990). Instead of trying to perfect the parser and provide the player with more freedom, Gilbert and Co. went the opposite route (the «Apple Route», if I might make an insinuation) and locked the player into the strategy of choosing your actions from a designer-preset number of choices rather than from the potentially unlimited inventory of your own brain, thus setting all adventure games on the inevitable path of getting dumbed down and mired in formula.

But this we realize only in retrospect; at the time, however, the interface of Maniac Mansion was utterly revolutionary — and even if you could no longer type in «fuck this stupid game» or «ask Dr. Fred about his political preferences», at least the choice of action verbs seemed large enough to satisfy the preferences and necessities of most adventure gamers. At this point, we are still far off from click wheels and minimalist interfaces of the LOOK / TALK / USE variety: in Maniac Mansion, you can push, pull, open, close, turn on, turn off, and even fix just about anything (though, of course, the number of various reactions to useless actions is notoriously limited). A lot of these actions are synonymously redundant: push / open / turn on smth. (like a radio, etc.) typically produce the same effect, which would, quite logically, lead to the minimalistic click wheels in the future — but even so, it does at least give you a sort of illusion of freedom of options. One oddity is that you cannot talk to anybody — but then again, you don’t really need to, since most of the people you encounter are bad guys, and talking to them is not a good idea in the first place.

In some respects, Maniac Mansion still lags behind contemporary Sierra products when it comes to making use of the graphic interface — for instance, there is no separate inventory screen with magnifiable pictures of your carried objects, just a text list at the bottom of the screen which you have to painfully scroll through. The much-lauded (at the time) mouse cursor remains clunky, and the alternate option to select and move everything with the keyboard is even clunkier. However, it’s nothing a patient gamer couldn’t quickly get used to even in the modern age. Also, save slots are pitifully limited, though this is not such a big problem considering you can very rarely die in the game and almost never (except for a few bugs here and there) get stuck in a dead end.

Verdict: Revolutionary and bizarr-ilarious

In but a few years, Maniac Mansion would become forever eclipsed by its sequel, Day Of The Tentacle — a fact which that game was so self-conscious of that, in yet another innovative move, it actually included all of Maniac Mansion as a playable game-within-a-game somewhere deep in its bowels. And yes, one hardly ever finds Maniac Mansion at the top of various best-of lists, what with all those other LucasArts titles like Monkey Island which came on its heels. But this state of affairs neither diminishes Maniac Mansion’s tremendous historical importance nor cancels the actual innocent joy of rediscovering it after all these years as an eminently playable title which has not lost its spark one bit and can still come across as hip and sarcastic (see, for instance, this silly, but charming 4-minute tribute by a completely new generation of fans).

Unfortunately, the game never got a proper remake or remaster: 1989’s VGA version, with mildly improved graphics and little else, was as far as LucasArts got away with this. (There was also a 2004 fan-made Maniac Mansion Deluxe project for Windows which borrowed the interface, along with a few additional Easter eggs, from later versions of SCUMM, but on the whole that kind of facelift did not seriously attempt to tamper with the original look). But then again, for instance, it is not clear how one should have approached the issue of voicing the game — what with its original severely minimalist dialog and all — and, overall, maybe its original look should remain untampered with. It is, after all, LucasArts’ firstborn adorable baby, and some people are best remembered as adorable babies.