Tracks: 1) The Gulley; 2) Twistaroo; 3) Trackdown Twist; 4) Potatoe Mash; 5) It’s Gonna Work Out Fine; 6) Steel Guitar Rag; 7) Doublemint; 8) The Rooster; 9) Prancing; 10) Katanga; 11) The Groove; 12) Going Home.

REVIEW

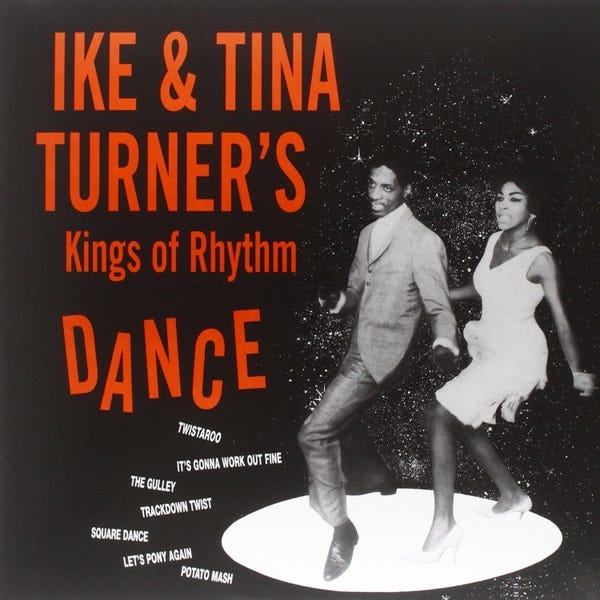

Before moving on to the proper second album by Ike & Tina Turner, I have sort of a bizarre, if not altogether unpleasant, quasi-contractual obligation to say a few words about this strange LP, billed as Ike & Tina Turner’s Kings Of Rhythm Dance and, rather appropriately, featuring both Ike and Tina on the front sleeve — however, true to the title, I suppose that the maximum possible contribution by Tina to this album is, indeed, dance (provided she’d be allowed to or willing to dance in the recording studio, which is not highly likely — that’s more of a Yoko Ono thing, if you ask me), and that activity is a little hard to appreciate within the context of a long-playing vinyl record. It’s easy to reconstruct the situation, though: by early 1962, Tina was the undisputed star attraction within Ike’s touring band, which must have irked him a bit, prompting the desire to prove himself once again on an album of guitar-oriented instrumentals — but since Tina was the star attraction, picturing and namedropping her on the front cover was considered a wise commercial move.

I almost admire how the liner notes on the back, written by radio DJs Jimmy Byrd and Reggie Lavong, while singing the praises of Ike’s band, never even once mention or strongly imply that the entire album is completely instrumental. You could actually walk into the store, carefully read the entire text, fork over your money and walk away assured that this is going to be a great record full of awesome playing and singing, and look! It’s got ‘It’s Gonna Work Out Fine’, these guys’ latest and hottest hit single, on it! What a great deal! Sure, they pay the standard tribute to the twist craze and everything, but then again, surely this Tina chick can rock the twist along with the best of ’em, right?..

Well, if we were to rate this record purely in relation to the primitive «there’s a sucker born every minute» mentality of early 1960s’ record labels (a mentality that was quite possibly shared by Ike himself, given certain shadowy aspects of his reputation), I would at best give Ike & Tina Turner’s Kings Of Rhythm Dance a one-sentence passable mention and ignore its contents altogether. As it happens, though, the LP is not at all bad, once you manage to distance yourself from unsavory thoughts on dishonest marketing practices and simply treat it on par with all the other rock’n’roll-related instrumental albums from the same era — by the Ventures, Duane Eddy, Booker T & The MG’s, etc. Ike was, after all, the grandaddy of them all, churning out energetic R&B instrumentals since the early 1950s; his desire to keep up a steady musical profile in the new era of blues-rock and surf-rock was understandable, and his ability to do that undoubtable.

Mind you, not every guitar player who’d made it big in the 1950s was capable of adapting his style to the new sounds and styles of the next decade — but Ike clearly kept his ear close to the ground, picking on new developments from fresher talents like Freddie King, and combining his traditional ways of playing with newer production techniques and string-picking methods. He cheats like crazy when taking most of the songwriting credits for himself, without even bothering to seriously mask it: for instance, the album opener ‘The Gulley’ is quite transparently an instrumental cover of the Olympics’ ‘Hully Gully’ — but he does modify it in such a way that it is no longer a dumb-cheerful party song, but a suggestive and menacing blues-rock instrumental. The opening verse is completely bluesy, with the Freddie King-style guitar reveling in reverb-drenched nastiness; and as the horns kick in to announce the ‘Hully Gully’ theme, Ike counteracts them by alternating between mean ’n’ lean «scratch guitar» riffage, shrill wailing lead lines, and vibrating power chords whose chief power is in their unpredictability — for a guy who prided himself so much on musical discipline, he allows his playing quite a lot of back-and-forth musical freedom.

Or, next in line, you probably would not expect much from anything called ‘Twistaroo’, and it’s basically an extra two-minute coda to ‘The Gulley’ with largely the same melody, but it’s not about the slow dance rhythm — it’s all about more of that scratch guitar, those stinging high-pitch lead lines, and that cool ability to strike your power chord and then make it wobble through the air. I am not sure exactly at what moment Turner started relying so heavily on the whammy bar, but he was definitely one of the first guitarists to do so on a systematic basis, and Dance is a good place to get acquainted with this early exploit without getting distracted by anything else. Let’s just take it one step further and say that without this album, there would be no Jeff Beck or Jimi Hendrix — both of them big lovers of the whammy bar — and that I also hear quite a big influence here on Keith Richards, whose early blues soloing style on the Stones’ pre-Aftermath records borrows more than a few tricks probably learned from Ike’s instrumentals.

That said, the album as a whole is rather monotonous: it’s all about that scratch guitar groove, backed by thick, meaty saxophone work and eventually exploding into frantic whammy-assisted soloing. The main difference is the tempo — on tracks like ‘Trackdown Twist’ and ‘The Rooster’ things speed up quite notably — but the vibe still remains exactly the same. The only single culled from these sessions, ‘Prancing’, is slightly longer than all of its competition, giving Ike a better chance to stretch out and pull all the stops, but they’re pretty much the same stops as in everything else on here. The rhythm is more straightforwardly bluesy than on the «twistified» tracks, perhaps — somehow the vibe is not affected by that at all, though. If you were playing the LP at a dance party, nobody’d blink an eye.

The only true exceptions are ‘Steel Guitar Rag’, a variation on Duane Eddy’s ‘Detour’-like instrumentals with Ike trying to play in a more country-western, twang-enhanced style (this does not come nearly as naturally to him as it does to Duane himself, or to The Ventures, though he does get into the spirit of «Nashville shredding»); and ‘Katanga’, a track probably named after the contemporary Katanga Crisis in Congo, but sounding more Latin American to my ears than African — and being the only number on here which exclusively concentrates on the brass section rather than lead guitar (there’s a very shrill and passionately distorted trumpet solo in the middle).

In the middle of it all, we get a surprising instrumental rendition of ‘It’s Gonna Work Out Fine’, a song that somehow got an earlier release on LP (though not on single, of course) than the vocal version — with Ike’s lead replacing Tina’s vocal. The dialog between the lead guitar and the brass section is cute, but for the most part, Ike is just mimicking the vocals, which, paradoxically, makes the «best» song on the album into the least interesting example of his skills. Somehow I’m fairly sure Ike only put the thing on the album to ensure better sales; his playing is rigidly perfunctory on the track, contrasted with the experimental fun he’s been having elsewhere.

Another relatively «stiff» performance is placed at the end of the album: ‘Going Home’ is one more Duane Eddy-style twangy country-western number, replete with a touch of «guitar yodeling» at the end of each verse — but I do like how it gives the record a touch of completion and conceptuality. It’s a «ladies and gentlemen, we’ve entertained you enough with our brand new style of playing generic dance tunes, now it’s lights out and back to the farm» kind of moment, and, for a couple of minutes, it might even trick you into feeling like you’ve just sat through something really important. A deceptive feeling, perhaps — but hardly the most humiliating type of deception you ever had to live through.

Only Solitaire reviews: Ike & Tina Turner

" Let’s just take it one step further and say that without this album, there would be no Jeff Beck or Jimi Hendrix — both of them big lovers of the whammy bar — and that I also hear quite a big influence here on Keith Richards, whose early blues soloing style on the Stones’ pre-Aftermath records borrows more than a few tricks probably learned from Ike’s instrumentals."

But how do we know that they actually heard this record? Do you just mean Ike's general style and not this album itself (that would make more sense)?